This is not a film review of A Complete Unknown.

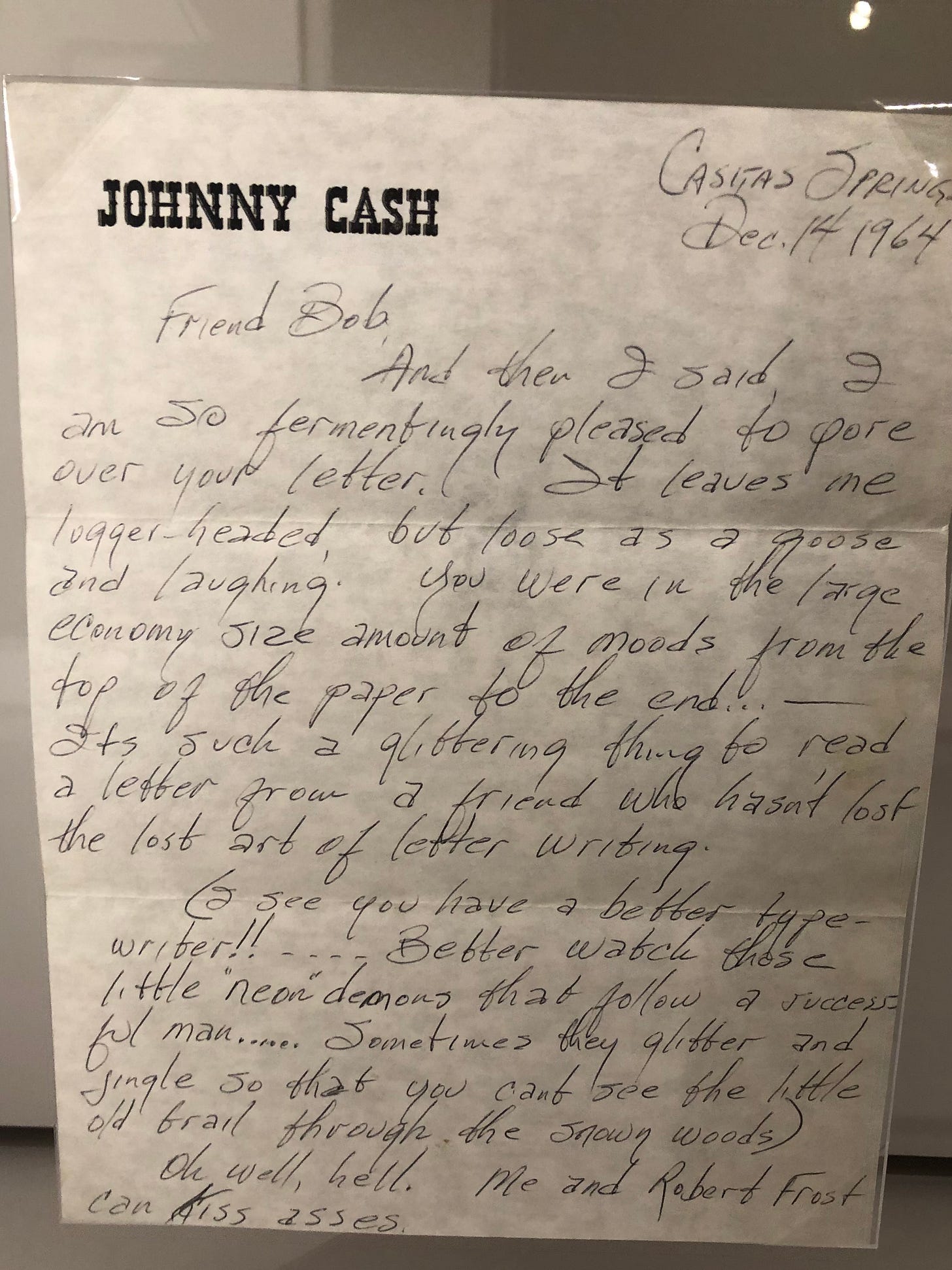

For what it’s worth, the film works great within the genre, introduces a new generation to Bob Dylan, and the man from the Iron Range (Dylan himself) approved and read lines in his own voice from the screenplay, before he approved it. The characters include a fellow rascal from another James Mangold docudrama, Walk the Line (Mangold might’ve enlisted Joaquin Phoenix to reprise his Johnny Cash, who’s now played by a better physiognomic match, the lean and wiry Boyd Holbrook—who looks great but comes off a little too boozy and bathetic, for my money, or Cash). But the film does include Chalamet’s Dylan reading a version of this correspondence from Cash (on display at the Bob Dylan Center in Tulsa, Oklahoma).

So, points for dramatized historicity. (Which is part of one critic’s lament about Oscar-nominated “Wikipics” in general, including A Complete Unknown (“Hollywood’s Time Machine is Broken,” by Matthew Gasda. For a positive take, you can read High Fidelity author and screenwriter

’s review, here.)The cast learned to sing and play their instruments, and recorded their own performances live, to great effect (even the always lovable, ever-cheesy chops of Pete Seeger, masterfully rendered by Edward Norton).

Chalamet positively disappears into the role of Bob Dylan—long, vampiric finger-pickin’ nails and all.

Which is what this article is really about: disappearing. Becoming “a complete unknown,” or an Invisible Man, for the sake of artistic flexibility.

See if these stories sound similar:

A nineteen-year-old student quits his small-town university one year before graduation. He moves to New York City, at the beginning of the Civil Rights movement. In the Big Apple, he discovers a gift for connecting with audiences. He’s embraced by the leader of a social movement with communist sympathies espousing the brotherhood of man. An interracial coalition, mostly directed by idealistic whites, interested in the “primitive” song forms of “the people.” The kid adopts a new name, then finds himself behind a microphone under bright stage lights, at the front of a social movement—becomes the voice of it.

The wunderkind receives more money than he’s ever seen, along with power and fame, plus plenty of adulation from the upper echelons of Manhattan society, particularly women—though he’s more fascinated with the music and fashions of the street, electric guitars and organs.

The baby-faced protege becomes disillusioned with the ideology of the community trying to co-opt him; he rejects and is disowned by it. He dons dark sunglasses for the sake of anonymity, experimenting with creative identity. In this guise, he’s often recognized, yet repeatedly mistaken for someone he’s not, and hounded like an animal in the streets.

The story climaxes with a riot that includes sharp weapons. The main character watches the community torn apart by the various factions of people who constitute it.

After a dangerous accident (a fall), the hero goes underground—to hibernate like a bear, and reflect on his unlikely role in American culture thus far. During this period of subterranean homesick blues, he tinkers with electricity and amplified sound, and listens to his favorite albums in his “basement.” One day, it’s foretold, he’ll reemerge under a range of new identities, his first step in becoming the artist he is today.

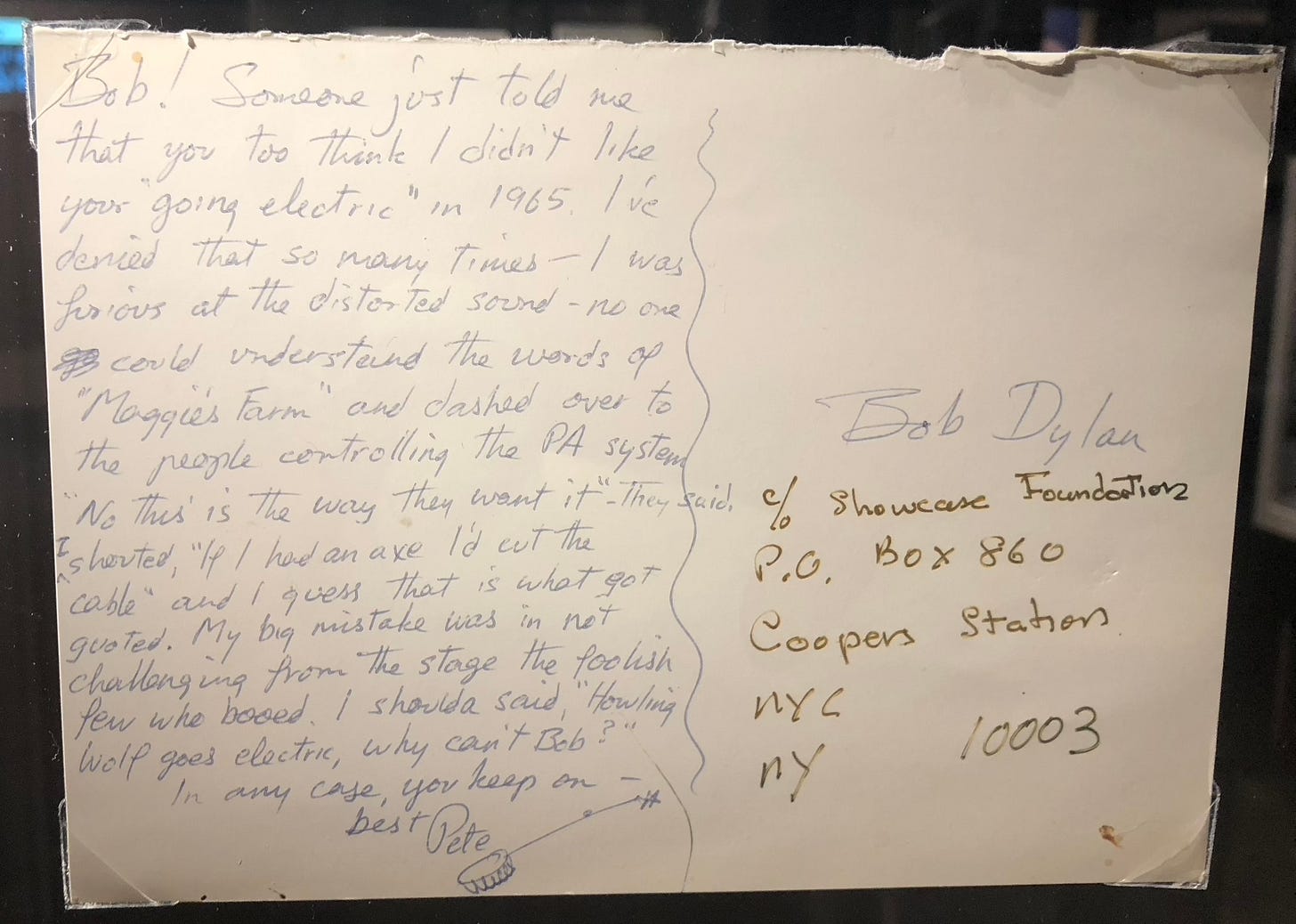

One is the story of nascent Bob Dylan. It’s the fodder for A Complete Unknown—from Dylan’s 1961 introduction to the Greenwich folk scene to his blasphemous debut (from the perspective of acoustic acolytes and folk purists) of electric guitar at the 1965 Newport Folk and Jazz Festival—the night that a soft-spoken elder spokesman for the folk movement named Pete Seeger allegedly tried to cut the power to Dylan’s PA system with an axe, while the other combatants (in the film, manager Albert Grossman and folklorist Alan Lomax) came to fisticuffs.

Here’s Pete Seeger’s apology for the incident, on a postcard (also on display at the Bob Dylan Center in Tulsa):

A Complete Unknown ends with Dylan speeding away from Newport on his Triumph Tiger 100, foreshadowing the motorcycle accident that would end this phase of his career. The fall forced him to recuperate in a remote house upstate, away from prying eyes, where he incubated a new strain of Americana—assisted by a crew of mostly-Canadian musicians obsessed with Southern roots music, known as The Band. Which produced a series of recorded sessions now known as, The Basement Tapes.

The other story is the plot of Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man (1952), the first novel by a black author to receive the National Book Award for Fiction in 1953—two years before Elvis became a force of nature covering black Southern roots music; around the time a twelve-year-old Bob Dylan, or Robert Zimmerman, was slinging a guitar around his Jewish summer camp, informing peers that, one day, he was going to be a rock star like Buddy Holly.

In Invisible Man, Ellison’s unnamed narrator (a complete unknown), leaves the constrictive ethos of a small-town university, deferential to whites in its dedication to black social uplift (based on Ellison’s alma mater, the Tuskegee Institute), for bustling Harlem—after he’s expelled for chauffeuring one of the school’s white founders to a juke joint inhabited by veteran mental patients.

Arriving in the the black mecca, Ellison’s Invisible Man is taken-in by “the Brotherhood,” a progressive group run by white idealists, ostensibly dedicated to racial uplift, but reminiscent of the American Communist Party, and cynically manipulative of black Harlemites in their “scientific” agenda for social improvement. Their leader, a white man named “Jack,” gives the Invisible Man a new name (still completely unknown to the reader), and props him up as the spokesman for the movement, “the next Booker T. Washington,” to Bob Dylan’s ‘next Woody Guthrie.’ He’s issued specific instructions for bringing the Brotherhood’s strategy of class struggle to fruition, which he excels at marvelously, for a while, using “the dynamic, mutual awareness required between performer and audience for an improvisation,” in the words of Ellison’s editor and executor, John Callahan.

But improvisation doesn’t suit the Brotherhood. The Invisible Man begins to go off script, following the death of a friend who’s already abandoned the Brotherhood himself. He delivers a controversial eulogy at his comrade’s wake (sort of like Dylan’s controversial ‘eulogy’ following JFK’s assassination, when he said he could see parts of himself in Lee Harvey Oswald). Both characters, young leaders of the movement, are deemed traitors.

Becoming disillusioned, Invisible Man begins to admire the individualist flair of Zoot-suited swingers he sees in the subways (“the true leaders, the bearers of something precious,”), developing his own burgeoning aesthetics of the blues—represented by his affinity with “The Devil’s Son-in-Law” Peetie Wheatstraw (a character in the book, and the name of an actual blues singer), and Louis Armstrong.

During his previous work with benevolent white racists in midtown penthouses, while doing their bidding in the streets, the Invisible Man’s “Brotherhood” is revealed to be at constant odds with another radical cohort, led by a West Indian named “Ras the Exhorter,” (aka “Ras the Destroyer”) — an uncompromising segregationist emblematic of Black Nationalism, whom the Invisible Man comes to despise as much as the Brotherhood.

Past is prologue: the novel ends where it begins, underground, after the Invisible Man falls through a manhole into subterranean New York, trying to escape the violent Harlem race riots above—white policemen on horseback, Ras the Destroyer with his spear and animal skins atop his own steed, and the manipulative Brotherhood watching their plan for “social progress” come to chaotic fruition from high above. Ellison’s hero is grazed by a bullet from an officer’s revolver, but as Bob Dylan sang in 2020, in “Murder Most Foul”—“you can’t shoot the Invisible Man.”

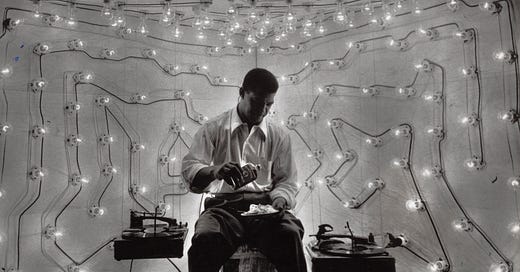

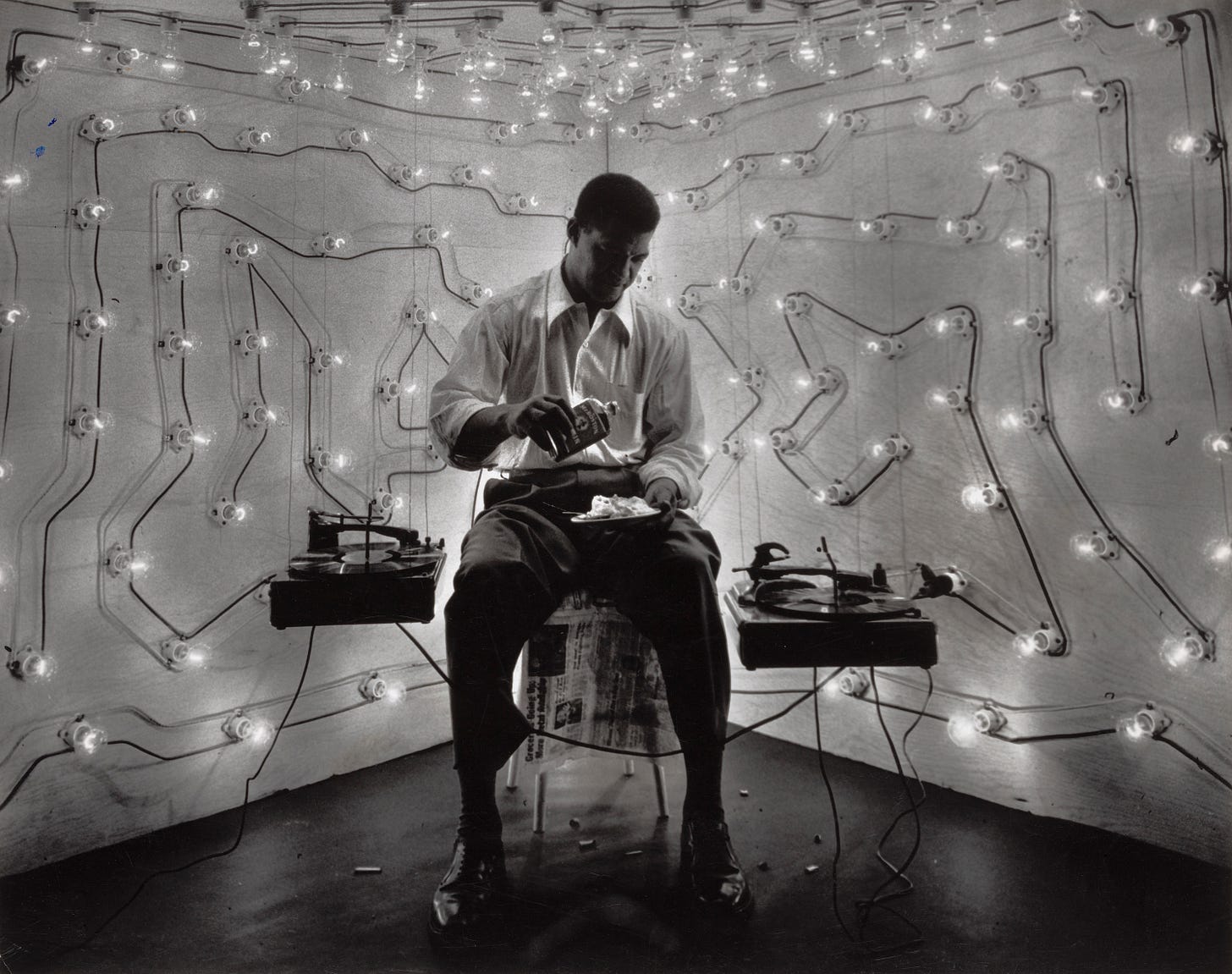

In the novel’s prologue and epilogue, underground, Invisible Man imbibes sloe gin over vanilla ice cream, a reefer “some jokers” slipped him instead of a cigarette, and listens to Louis Armstrong’s “(What Did I Do to Be So) Black and Blue?” on repeat, on the phonograph player, of which he “one day plan[s] to have five.” “Though invisible,” he says, “I am in the great American tradition of tinkers. That makes me kin to Ford, Edison, and Franklin. Call me, since I have a theory and a concept, a ‘thinker-tinker’.”

Ellison, a thinker-tinker himself, supported himself while writing Invisible Man with odd jobs, and, as he explains in the author’s introduction, “built audio amplifiers and installed high-fidelity sound systems,” which obsessed him. Before becoming a writer, he wanted to be a musician, on saxophone and trumpet.

“I am invisible, understand, because people refuse to see me . . . When they see me they see only my surroundings, themselves, or figments of their imagination,” his complete unknown begins the novel, sounding a bit like Bob Dylan rejecting the label of protest singer. “I am not complaining, nor am I protesting,” says the Invisible Man on page one.

“Invisibility,” John Callahan writes in the 2001 introduction, “invites those unseen or falsely seen to create their own version of identity and experience . . . invisibility, though brilliantly expressive of racial (and racist) blindness, extends far beyond the dimension of race.” Ellison called his ‘theory and concept’ of invisibility “the American theme,” the “beautiful absurdity” of American identity.

Self-creation.

To power his conceptual reinvention, along with reefer and gin, Invisible Man diverts electricity from the “Monopolied Light and Power” company, tapping into the utility’s mainline: “In my hole in the basement there are exactly 1,369 lights. I’ve wired the entire ceiling, every inch of it . . . an act of sabotage, you know. I’ve already begun to wire the wall.”

A Complete Unknown, I kept thinking as I pondered this oft-mythologized, self-sabotaging phase of Dylan’s career, might as well’ve been called Dylan Goes Electric! — which, it turns out, happens to be the title of folk historian Elijah Wald’s 2015 book about Newport, Dylan, Seeger, and the Night that Split the Sixties that inspired Mangold’s biopic: “a fantastic retelling of events from the early '60s that led up to the fiasco at Newport,”—in the words of one enthusiastic reviewer, Bob Dylan.

A Complete Unknown, like Dylan Goes Electric!, follows the same trajectory as No Direction Home, Martin Scorsese’s 2005 documentary (featuring enlightening interviews with Dylan and his contemporaries themselves)—his evolution from self-described “Woody Guthrie jukebox” straight out of Hibbing, Minnesota to electrified Judas.

A prolific period that culminated in the recording of three incredible albums, Dylan’s most creative outburst: the fourteen months between April 1965 and June 1966 when he released his first three electric albums, Bringing it All Back Home (April 1965), Highway 61 Revisited (Aug. 1965), and Blonde on Blonde (1966).

Not to mention an exhausting tour that produced a series of bootlegged live sets, half-acoustic and half-electric, some of them captured in D.A. Pennebaker’s cinéma vérité doc Don’t Look Back (1967), that were eventually released by Columbia Records three decades later, as Bob Dylan: Live 1966 (The “Royal Albert Hall” Concert) (1998)—a misnomer, actually recorded at the Manchester Free Trade Hall.

The recording in which, for all posterity, just before Dylan and the Hawks (soon to be The Band) launch into a blistering version of “Like a Rolling Stone,” a heckler screams “Judas!”, accusing Dylan of taking the silver—his supposed betrayal of folk ethics, for the commercial success of rock n’ roll.

It’s well-worn territory, the history leading up to Bob Dylan’s first chrysalis and metamorphosis, brought on by a flirtation with electricity and his falling-out with a group of pseudo-religious political ideologues. (For the sake of condensed storytelling, in A Complete Unknown, the Manchester “Judas” incident is conflated with the Newport Folk Festival. In similar fashion, Dylan’s farewell to folk, “Song to Woody,” is repurposed as his musical overture to his folk idol, performed at Woody Guthrie’s bedside in Greystone Park Psychiatric Hospital).

Like a convalescent Bob Dylan in upstate New York (following his own fall, from a motorcycle), Invisible Man can’t stay holed up forever after his fall beneath uptown Manhattan. After licking his wounds and narrating his story, “now that I’ve put it all down the old fascination with playing a role returns, and I’m drawn upward again,” the Invisible Man says.

It’s what John Callahan called, “Invisible Man’s self-mocking, ironic, qualified, and, therefore, all the more convincing resolve to emerge from hibernation and re-engage with the world,” as someone like Ralph Ellison, the writer.

“Self-mocking,” “ironic,” and “qualified” pretty well sums up this artist:

I mightn’t have noted the slightest parallel between Ellison’s character and Robert Zimmerman’s, between Invisible Man and A Complete Unknown, had I not read Ellison’s novel after seeing Mangold’s film. But as Ellison’s close friend remembers him saying sometime in the late 1940s, “Literary truth amounts to prophecy. [T]elling is not only a matter of retelling but also of foretelling.”

And who knows, maybe Dylan was one of the many readers who encountered Invisible Man “on the underground, word-of-mouth literary frequency of must-reading that went unassigned in classes” in the 1950s and early 60s, in the words of John Callahan. (He’d certainly read it by 2020, when he wrote the lyrics to “Murder Most Foul.”)

“HOW DOES IT FEEL . . .” Ellison’s character asks at the novel’s end, fourteen years before Dylan’s “Like a Rolling Stone,” “TO BE FREE OF ILLUSIONS”? How does it feel, to be on your own, like a complete unknown? You’re invisible now, you’ve got no secrets to conceal.

These resonances were only increased by this article, by Michael Moynihan: “The Truth About Bob Dylan’s Falling Out with Pete Seeger: The ’60s folk singers didn’t hate Dylan because he went electric, as ‘A Complete Unknown’ suggests. It was because he didn’t care about their lefty politics.”

Moynihan enumerates a fairly comprehensive list of disgruntled fellow-travelers, communist folkies incensed by Dylan’s betrayal of their politics at the 1965 Newport Folk and Jazz Festival. Not least his former girlfriend and duet partner Joan Baez, who, in her words, “wanted [Dylan] to be a political spokesperson. . . to be on our team.” In her memoir, Baez also complained that Dylan’s “active commitment to social change was limited to songwriting,” and, in Moynihan’s words, she dinged him “for never going on a protest march or engaging in civil disobedience” (never mind that Dylan performed “Blowin’ in the Wind” on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial shortly before Martin Luther King delivered his 1963 “I Have a Dream” speech). In a 1972 song, “To Bobby,” Baez blasted Dylan again for not sharing her activism, proselytizing that, should he return to the social justice politics of the 1960s, “[God] will forgive you.”

One of the more perfect asides in the film is a bit of flirtatious criticism from Chalamet’s Dylan regarding Baez’s cloying aesthetic: “How about that Joan Baez, folks? She’s pretty good. And she’s pretty. She sings pretty. Maybe a little too pretty.” And in a more private moment, “[Joan,] Your songs are like an oil painting at the dentist’s office.” To which Monaco Barbaro’s Baez retorts (a common response to Dylan’s demeanor in general): “You’re kind of an asshole, Bob.”

Ellison received backlash of the Baez variety a decade before Dylan. Though Invisible Man was lauded by writers like Saul Bellow, Wright Morris, and Lou Reed’s future Syracuse professor and lyrical mentor, the poet Delmore Schwartz, Callahan explains:

Not all reviewers were so positive. Some, mostly defenders of the Communist Party and Black Nationalism - two ideologies that took a beating in the novel - considered Ellison’s book the work of the devil’s own son-in-law. In the Daily Worker, Abner Berry characterized the book as “439 pages of contempt for humanity, written in an affected, pretentious and otherworldly style to suit the king-pins of white supremacy” . . .

However that kind of criticism proved shortsighted. Larry Neal, “a leading figure in the Black Arts Movement," per Ellison’s editor and executor, “who had quarreled with Ellison and his work earlier in the 1960s, declared in Black World, a journal repeatedly hostile to Ellison . . . ‘Dig. Here is your black aesthetic at its best.’” Forty years later, the black novelist Charles Johnson, dismayed that Invisible Man was “snubbed by those under the spell of black cultural nationalism” in the 1960s, would dedicate his own National Book Award acceptance speech to Ellison.

Pete Seeger, who begins A Complete Unknown defending himself with a banjo during a Red Scare court hearing, left to tour the Soviet Union after the Dylan fiasco at Newport. “Perhaps a line or two indicating that Seeger defended Joseph Stalin throughout the genocidal Ukrainian famine, the bloody purge trials, the antisemitic “Doctor’s Plot,” the Soviet alliance with Nazi Germany, and their subsequent dismemberment of Poland,” Moynihan writes, would have elucidated the vehement reaction to Dylan’s simple act of plugging in an electric guitar: it was about politics and identity, not aesthetics.

When Chalamet-as-Dylan plugs-in to sing “I ain’t gonna work on Maggie’s Farm no more” in A Complete Unknown, for the first time, it finally clicks that (to paraphrase Matt Welch), it was a big Fuck You! to Pete Seeger and political correctness, not forced labor.

“[Dylan] was not interested in the true nature of the Soviet Union, or any of that crap,” said fellow Village folksinger, and erstwhile Marxist Dave Van Ronk. “We thought he was hopelessly politically naive. But in retrospect, I think he may have been more sophisticated than we were.”

Aside from “Maggie’s Farm,” and self-mocking, ironic interviews, Dylan did everything he could to escape his political designation as a “protest singer” “voice of a generation” in 1965—including hiding behind dark sunglasses, like Ellison’s Invisible Man, who in this disguise is mistaken for a combination numbers-runner, Reverend, ladies man, and rounder he’s never heard of, ensconced as he is in the rigid politics of “the Brotherhood.” A grifter named “Rinehart.”

Rine the runner and Rine the gambler and Rine the briber and Rine the lover and Rinehart the Reverend. Could he himself be both rind and heart? What is real anyway? He was a broad man, a man of parts who got around. Rinehart the rounder. It was true as I was true. His world was possibility and he knew it. He was years ahead of me and I was a fool. I must have been crazy and blind. The world in which we lived was without boundaries. A vast seething, hot world of fluidity . . . It was unbelievable, but perhaps only the unbelievable could be believed. Perhaps the truth was always a lie.

Ellison, for his part, told friend Albert Murray in a 1951 letter that the novel was “a big fat ole Negro lie, meant to be told . . . at a good fast clip so that no one, not even the narrator himself, will realize how utterly preposterous the lie actually is.”

Consider all the lies Robert Zimmerman’s told — his name, coming to New York as a boxcar hobo, being a carnival barker, a cowboy singer. Consider all the dice Bob Dylan’s rolled, with his career. Consider all the roles in which he’s been enrolled, including this latest one.

2007’s I’m Not There features six different characters emblematic of the various versions of “Bob Dylan,” played by six different actors, and that just begins to scratch the surface of his multiplicity: an eleven-year-old African-American tramp calling himself “Woody Guthrie”; a folk-singer turned ordained minister named Jack Rollins/Father John (played by Cate Blanchett); the 19th c. Symbolist poet Arthur Rimbaud; a version of Billy the Kid (Heather Ledger, in his final film released before his death), etc…

In the words of Walt Whitman, and later Dylan himself “I contain multitudes.”

Invisible Man has his epiphany about Rinehart’s multiplicity outside the doors of a converted store-front church where the Reverend is preaching “the NEW REVELATION of the OLD TIME RELIGION! BEHOLD THE SEEN UNSEEN! BEHOLD THE INVISIBLE.” (As Dylan sang in his elegy for an electric guitar player, decades later, Goodbye Jimmy Reed, Jimmy Reed indeed. Give me that old time religion, it’s just what I need.)

“That’s the new kind of guitar music I told you Rever’n Rinehart got for us,” one congregationalist says outside the church, referencing a young man inside striking “righteous riffs from an electric guitar which was connected to an amplifier that hung from the ceiling above a gleaming white and gold pulpit.”

This is a portrait of 1930s-1940s Harlem, mind you. Rinehart’s flock might be devout, but they’re hip to the con, and the con works for them, religiously and aesthetically. They’re less dogmatic than the Brotherhood, or the Greenwich folk movement twenty years later, when it comes to musical and spiritual innovation.

Dylan, like Rinehart, is an individual of fluidity and multiple, career-spanning identities. He conceives of himself as trickster. Like Ralph Ellison and his Invisible Man: “Ulysses,” or “Brer Rabbit.” (He once told an interviewer in No Direction Home with a straight face that his first two girlfriend’s names were “Gloria Storia” and “Echo”). Michael Moynihan again:

One of Bob Dylan’s greatest tricks, in a career full of them, is his endless provocation of academic charlatans, credulous journalists, and his army of Aspergerian superfans. Those opaque lyrics and infrequent interviews—full of tall and contradictory tales, deeply entertaining and obviously false—have left a trail of breadcrumbs that lead off a cliff.

Here’s a personal favorite, an MTV interviewer trying to pigeon-hole Dylan on gun control in 1993. A “portrait of the artist as rabble-rouser,” as Ellison described Invisible Man.

I was introduced to this interview during a panel on Dylan’s oft-overlooked humor, and it reminds me of Ellison’s greatest complaint about the reception of his novel. Not that it was a “pretentious” gift to “the king-pins of white-supremacy” according to communists and black nationalists—his biggest complaint was that no one saw the generous humor in it. He’d hoped the novel would be received as “a comic antidote to the ailments of politics.” Reveling in the hot fluidity and “beautiful absurdity” of American identity.

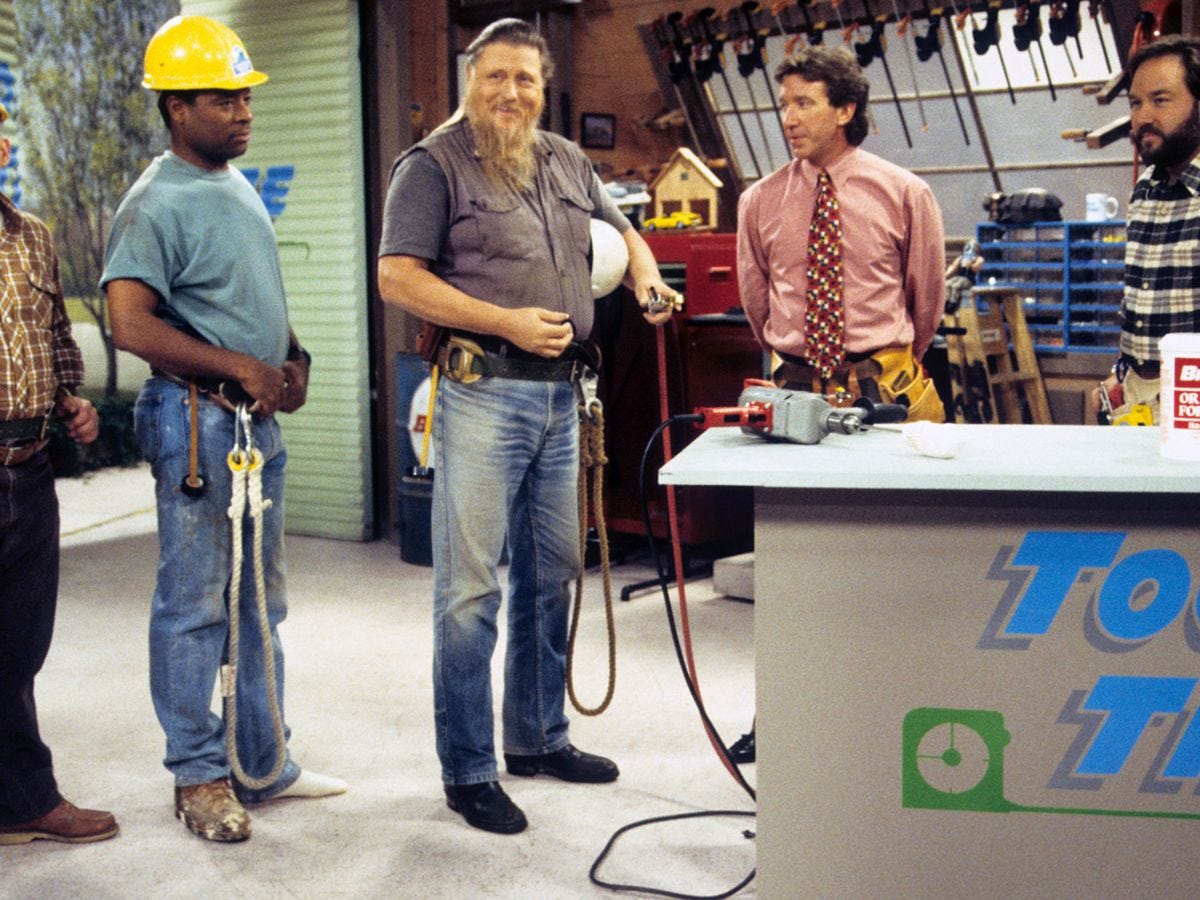

Case in point for beautiful absurdity: here’s the drummer for one of the most ground-breaking backing bands in rock history, who was there when Manchester screamed “Judas,” in a recurring role on one of the most banal series in television history.

The title of A Complete Unknown comes from the chorus of “Like a Rolling Stone.”

The line directly before it inspired the title of Scorsese’s No Direction Home (which as Dylan reveals in the documentary, if we can take him seriously, is part of his conception as an artist, another Ulysses, “with a feeling of being not quite at home,” but always searching for one).

As journalist Sarah Hepola recently pointed out, to her initial irritation about the film’s title, this is a trifle unoriginal, for such an original subject: can’t we come up with something different? It’s the very next line in the same song! But A Complete Unknown turns out to be an apt descriptor for the invisible quantity that is Bob Dylan, the cagey changeling who thwarts audience expectations, rarely grants interviews, and when he does, intentionally misleads inquisitors.

In the annals of rock and roll history, the earliest reference to a “rolling stone,” as far as I know, comes from bluesman Muddy Waters—who also found success ‘going electric,’ long before Bob Dylan. Like the words “rock and roll,” it comes from black-and-blues history.

From the lyrics of “Catfish Blues” and “Mannish Boy” the Rolling Stones took their name in 1962, and paid Muddy Waters a visit, in Chicago, to acknowledge it. In 1965, Dylan wrote a song about being invisible, borrowing the Muddy Waters phrase again for its title. In 1967, Jann Wenner named a magazine after all of the above.

Despite its transitory theme, “Like a Rolling Stone” seems to have staying power. It’s become a sort of anthem, a meme for documentarians as well as Dylan himself. He still plays it live from time to time, unlike many of his other early 60s hits. As he says in No Direction Home:

“An artist has to be careful never really to arrive at a place where he thinks he's at somewhere…. You always have to realize that you are constantly in a state of becoming, and as long as you can stay in that realm, you'll sort of be alright.”

Improvisation, rolling with it, the ability to transcend life’s circumstances “by squeezing from it a near-tragic, near-comic lyricism,” was Ellison’s own definition of the blues. “The old fascination with playing a role.”

It made Invisible Man “par excellence the literary extension of the blues,” in the words of Ralph Ellison and Duke Ellington’s close friend, also Count Basie’s biographer, a music and literary critic named Albert Murray.

Albert Murray was (in)famous for claiming, in his 1970 book of literary and cultural criticism, The Omni-Americans:

American culture, even in its most rigidly segregated precincts, is patently and irrevocably composite. It is, regardless of all the hysterical protestations of those who would have it otherwise, incontestably mulatto. Indeed, for all their traditional antagonisms and obvious differences, the so-called black and so-called white people of the United States resemble nobody else in the world so much as they resemble each other. And what is more, even their most extreme and violent polarities represent nothing so much as the natural history of pluralism in an open society.

In his epilogue, Ellison’s narrator comes to a similar realization:

Whence all this passion toward conformity anyway? - diversity is the word. Let man keep his many parts and you’ll have no tyrant states . . . America is woven of many strands; I would recognize them and let it so remain . . . Life is to be lived, not controlled; and humanity is won by continuing to play in face of certain defeat. Our fate is to become one, and yet many - this is not prophecy, but description. Thus one of the greatest jokes in the world is the spectacle of the whites busy escaping blackness and becoming blacker every day, and the blacks striving toward whiteness, becoming dull and gray. None of us seems to know who he is or where he’s going.

This is what John Callahan calls “the evasion of identity Ellison felt characteristic of the American experience.” This was written in 1952, of course, and today we may be escaping from the opposite direction. None of us seems to know who we are or where we’re going, but most pretend to, and few evade identity.

I’m reminded of this sort of narrow-mindedness in a scene from A Complete Unknown where Alan Lomax refuses to include the Paul Butterfield Blues Band in the Newport Festival lineup because they’re not ‘authentic’ (black) blues players.

When Charles Johnson dedicated his National Book Award speech to Ellison in 2002, he gestured towards “the emergence of a black American fiction that is Ellisonesque in spirit, of increasing intellectual and artistic generosity, one that enables us as a people - as a culture - to move from narrow complaint to broad celebration.”

He could have been speaking of black people and culture, or of American culture in general. As Ellison said, “the true American, whatever else he is, is also somehow black.”

The words to “Like a Rolling Stone” and Invisible Man, and all the associated lyrics in the American confluence, seem to bear this out.

And the true American, whatever else he is, if Ellisonesque in the spirit of increasing intellectual and artistic generosity, is also somehow white—or Russian, or whatever else. Ellison, like the Beat writers who inspired Dylan, associated himself and his narrator, “ever so distantly, with the narrator from Dostoevsky’s Notes From Underground,” in his words.

The words of an old slave woman revealed to Invisible Man in a hallucinatory fever might as well apply to Bob Dylan or anyone else, when it comes to art and freedom from generic constraints: “freedom ain’t nothing but knowing how to say what I got up in my head.”