Culture war conjures images of overheated political factions, pitching ideological battle over wedge issues in a bid for power—online, in media, or in the streets. The notion of a Kulturkampf was born out of a church/state struggle in Prussia, circa the unification of Germany from a loose constellation of kingdoms and principalities in the 1870s.

This is not that kind of culture war.

But there may be a degree of unification, or at least conversation, involved.

As an antidote to the Madness of Crowds (Charles MacKay’s compendium of popular delusions that informed my series on #witchhunts), many of the reading selections this week were inspired by the Wisdom of Crowds — a Substack co-founded by two Opinion journos from The Washington Post (not exactly a hothouse of Socratic dialogue in recent years, perhaps the reason they branched out). A platform organized “against consensus,” committed to open debate “over the first principles at stake in political, cultural, and social questions.”

WoC showcases of variety of voices, from a variety of critical perspectives, in one masthead.

In the realm of cultural criticism, the “culture war” at hand is not about which political contingent is ascendent at the moment, but the definition of culture itself. And whether it’s dead, stagnating, “stuck”… or so marvelously new as to be undefinable.

Some recent examples, from the “culture is stuck” camp (links underscored):

Is Culture Dying?

The French sociologist Olivier Roy believes that “deculturation” is sweeping the world, with troubling consequences.

Joshua Rothman, The New Yorker

Why Do I Keep Saying the Culture is Stagnating?

We live in an age of innovation, so how can I claim otherwise?

Ted Gioia, The Honest Broker

The Decline of the Novel

It’s worse than you think

The New Culture War Is Real Vs. Bogus

My latest arts and culture briefing

Culture is Stuck

Paul Skallas, The Lindy Newsletter

The observations in pieces like these are acknowledged, and helpfully, at the beginning of the following essay, by Katherine Dee—who kickstarted this critical tete-a-tete earlier this month, in her riposte to the pessimists:

No, Culture is Not Stuck

You just can’t see what it’s become.

To recap: the novel is obsolete. A New York Times critic is asking whether we even need great literature, or the Nobel Prize.

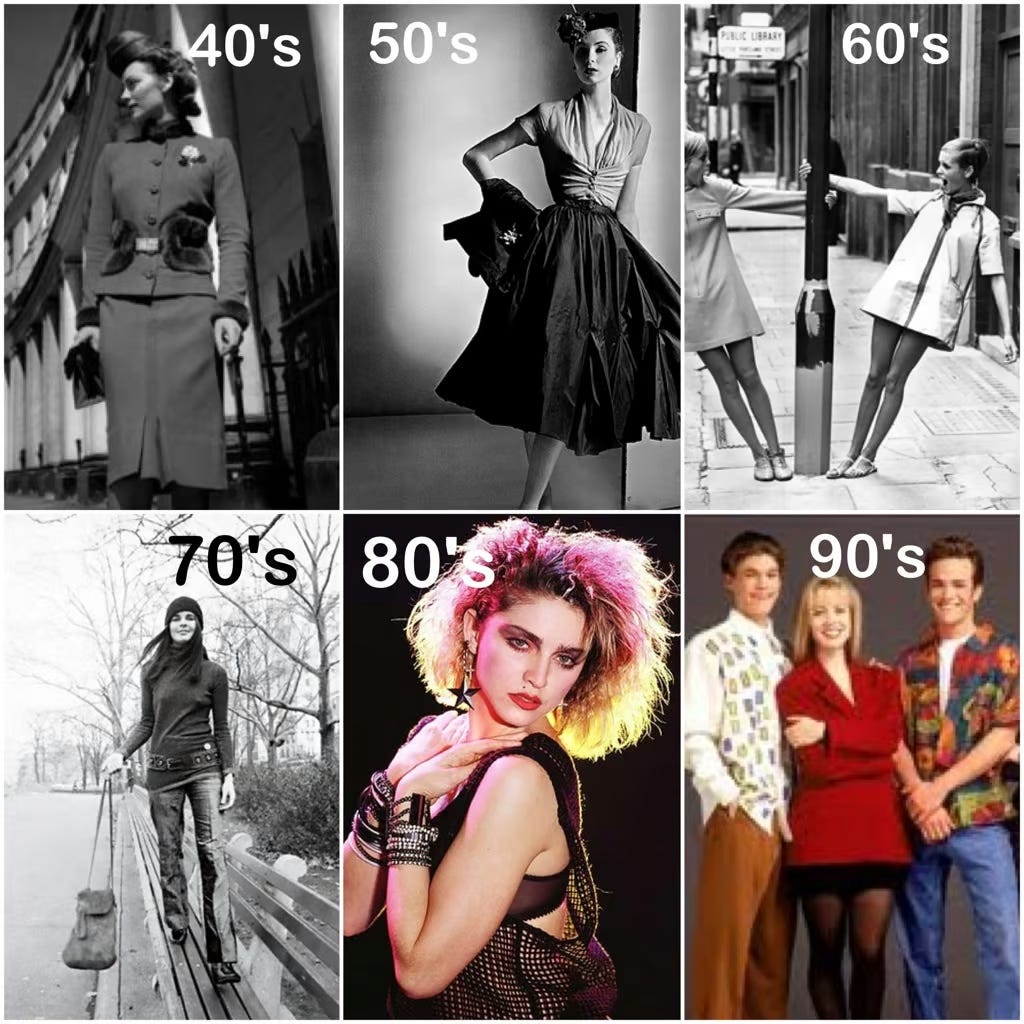

Students at elite universities can’t read books (The Atlantic). Cinema is swamped with sequels and reboots. People are increasingly listening to old music, and ignoring the new (Honest Broker). Even fashion is redundant—“If you time travel back to 2007 wearing what you wear now people wouldn’t know you’re from the future”— clothing styles have hardly changed since then, compared to previous decades (Skallas).

“Culture used to be something we did for its own sake; now we do it to position ourselves vis-à-vis other people […] this means that it’s dying […] ‘Ways of believing’ now come within the realm of subcultures; they are associated with sects, fandoms, conspiracy theories and the like.” (The New Yorker)

Culture “has no positive aspect, since the old culture has been delegitimized and the new one does not meet the necessary condition of any culture, which is the presence of implicit, shared understandings” (The Crisis of Culture: Identity Politics and the Empire of Norms, Olivier Roy).

Katherine Dee, on the other hand, points to the obsolescence of older types of culture, while noting the evolution of new ones:

Theater is a good example of what I’m talking about. Once a dominant art form, theater ceded its cultural primacy a long ago. People still produce and even write excellent plays and musicals, even today, but it’s no longer the primary vehicle for cultural expression and innovation. It’s a niche. Similarly, film, fashion, literature, or even music as we once knew them are no longer the primary mediums through which new and exciting culture is experienced. They haven’t completely gone away, but the landscape has changed so radically that they shouldn’t be the metric we use to measure the progress of culture.

We’re witnessing the rise of new forms of cultural expression. If these new forms aren’t dismissed by critics, it’s because most of them don’t even register as relevant. Or maybe because they can’t even perceive them.

Ted Gioia reduced Katherine Dee’s apologia to this:

“Last week, a highly touted essay announced that, hey, it’s okay that the novel and film are dying, because (wait for it) … we now have cooler online stuff, like Instagram twerking videos and Twitter shitposting. If this is the good news on culture, I’d hate to hear the negative take.”

To be fair, despite the numerous cultural canaries in the coal mine languishing in Gioia’s reporting, he does see signs of hope: live music is undergoing a resurgence. Small cinemas are popping up, backed by huge names in Hollywood. And there’s Substack, a haven for exiles from legacy media and big publishing, which Gioia posits as no longer just the petri dish of a new literary counter culture, but the breeding ground of novel “multichannel media empires.” But these are “microcultures” at the moment—subcultures, or small, localized scenes, not the “macroculture” of yesteryear, based on top-down media and corporate gatekeepers like CBS or RCA—as Lester Bangs predicted in 1977, after the death of Elvis Presley:

We will continue to fragment in this manner, because solipsism holds all the cards […] it is a king whose domain engulfs even Elvis's. But I can guarantee you one thing; we will never agree on anything as we agreed on Elvis. So I won't bother saying goodbye to his corpse. I will say goodbye to you.

“Macroculture,” or what we used to simply call “culture,” amounts to the “presence of implicit, shared understandings,” in the words of French sociologist Olivier Roy. Something capable of transcending new offshoots, and new technologies, and absorbing them into an established tradition—“a vineyard,” as opposed to a “meth lab,” in the words of one of the critics below, Matthew Gasda.

The cultural optimism Dee espouses is more of the “meth lab” variety—TikTok videos as performance art, or a new medium for sketch comedy, for example.

I don’t endorse Dee’s characterizations of everything—in particular I think it’s a stretch to suggest that certain “anonymous creators” online (as opposed to fame-thirsty influencers, or “the Internet-Personality-as-Art” ) evince an “approach to authorship [that] is almost medieval: their projects are not about them as individuals, but the meme, the project, the aesthetic, the vision. They are less like the expressive individualists of Modern art, than the cathedral builders of the Middle Ages.”

However I appreciate her somewhat dubious attempt to situate novel ‘art forms,’ such as they may be, in a longer tradition, which is point of criticism, and culture.

Santiago Ramos, executive editor of WoC—fast becoming one of my favorite critics—goes so far as to compare Dee to the disinterested prophet of the Internet Age, media theorist Marshall McLuhan.

And Ramos makes a good point:

…because Dee is approaching things similar to the way McLuhan was, her technique requires a temporary suspension of judgement. The “technique of suspended judgment,” which McLuhan learned from Bertrand Russell, is “the discovery of the process of insight itself, the technique of avoiding the automatic closure or involuntary fixing of attitudes that so easily results from any given cultural situation.” This approach is, McLuhan continues, a “technique of open field perception,” that positions you to absorb data without prejudice.

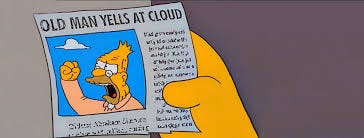

Absorbing data without prejudice is an indispensable modus operandi for anyone wishing to interpret the Online. Dee, an “Internet anthropologist,” does research incisively the inane internet subcultures shaping our politics, attention spans and perception, while mostly avoiding the value judgements of her older colleagues—whose Jeremiads, she readily admits, are more than just “Old Man Yells at Cloud” complaints.

The old culture, Dee concedes—books, film, music—are indeed in crisis.

Ramos offers the most measured response to the fervor surrounding Dee’s essay in the following assessment, applauding her McLuhanesque perception, but cautioning against suspending aesthetic or spiritual judgement altogether:

It's OK to Suspend Your Judgment (But Not Forever)

On Katherine Dee and her critics.

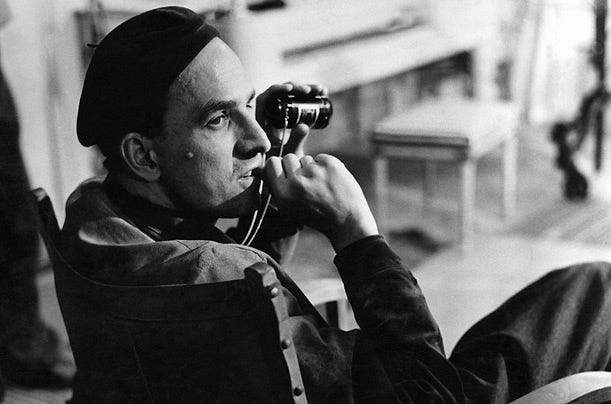

I do have Dee to thank, for invoking an incredible artifact of film and literary history—a page torn from Tennessee Williams’ copy of Four Screenplays of Ingmar Bergman (1960), which the Southern playwright memorized and recited often, as a sort of aesthetic prayer he borrowed from the Swedish director:

Ingmar Bergman: Building the Cathedral

(Very brief, highly I recommend, along with Bergman’s filmography.)

Bergman’s essay comparing filmmaking to the rebuilding of Chartres cathedral, curated and anointed by Tennessee Williams, is alone worth stomaching Dee’s comparison of anonymous meme lords to the same tradition. And it’s refreshing to hear her perspective on new forms of art, even if many of them appear to be garbage…

(Thanks to Sarah Hepola for the hilarious example above—and sparing me a visit to TikTok.)

Dee:

Much has been said about memes as art and the collective labor and imagination that goes into their creation, but it extends further than that […] Many of these aesthetics have staying power […] They’re not passing fads or stand-ins for personalities or subcultures. They are more than ever-evolving vectors for consumerism. They’re a type of immersive art that we don’t yet have the language to fully describe.

But that is the case with so much of what’s new. We won’t understand it until it’s in the rearview mirror. Culture isn’t stagnating; it’s evolving in ways that we’re struggling to recognize and appreciate. The challenge lies not in reviving what’s dead, but in developing the language to understand what already exists.

Dee excels most at approaching online culture as insider anthropology — but she falls short arguing that internet subculture is the same as capital “C” Culture — which, as the most forceful retort to Dee’s piece points out, requires more than novelty or formal innovation:

The Vineyard and the Meth Lab

Yes, culture is stuck.

Matthew Gasda, Wisdom of Crowds

Cultures have souls: values, goals, material and spiritual traditions. They take time to develop, if they develop at all. They require labor, development, and the gradual vetting process of time. Culture is not stuck or stagnant, if this, however gradual, maturation process is ongoing; if time is sculpting and selecting. Culture doesn’t require overnight innovation; it requires ripening, fructifying. Behind the Renaissance was hundreds of years of gradual spiritual and technical development in Europe (a vineyard is the easy metaphor); behind Internet culture is yesterday, or today, or ten seconds ago (a meth lab is a possible metaphor).

Katherine Dee is wrong: new forms, alone, don’t save a culture from lassitude and decay; new forms can be empty; new artists can be con-artists. Innovation without soul is pointless. Is innovation in the realm of porn (OnlyFans) or broadcasting (Barstool) supposed to convince cultural pessimists that they’re conventional, conservative, and blind? Digital culture that “innovates” with garbage is just finding new ways to feed us garbage; zero times zero is zero.

Displays of newness are not displays of soulfulness. Innovation must coordinate with complex cognitive processes, formal ambition, respect for tradition. High European modernism, for example, absorbed moving images and the music hall because it was an ultra-literate culture with a high level of general education and exacting standards. It wasn’t good because it made use of new media and mediums; it was good because it was able to transcend them. New ideas and phenomenologies, like types of grape, took root in cultivated soil.

The lack of “cultivated soil” — the inability of Ivy League students, let alone high schoolers, to finish a novel, or understand it where it came from, for example — is the substance Dee’s assessment overlooks. But her insights into online subculture are crucial to understanding the broader culture, such as it is, today. While I’ve been struggling to comprehend 2020, “Katherine Dee is a writer trying to uncover what happened between 2008 and 2015, ” as her bio for the following article explains.

In that window of time:

Tumblr Transformed American Politics

Identity as it now defines our discourse found its origins not in the ivory tower but in the realm of online fandom.

Ironically, the least conservative of the critics embroiled in the “Is Culture Stuck?” debate cut her teeth on this piece, from The American Conservative (don’t let that throw you, her work appears in publications with a wide range of ‘politics’).

What Dee noted at the time, in 2021—that the weirder fringes of leftwing culture-war ideology were incubated on the fandom-obsessed social media platform Tumblr—was documented two years later by Megan Phelps-Roper in The Witch Trials J.K Rowling (where Phelps-Roper also posits 4Chan as the rightwing corollary to Tumblr, in the same culture war).

This is Dee’s “Internet anthropology” at its weirdest best, divorced from any specious arguments about whether her findings constitute Culture. What she reveals is a series of tribal identities based on totemic worship of cult artifacts—in this case, pop cultural products like Harry Potter, Doctor Who, and One Direction. In other words, “fandoms,” born on Tumblr.

Fans aren’t just people who like or even love something (and really, it can be anything, from a film to a TV show to a politician, everything and anything is fair game). They are people who participate in that love, with others, through a variety of different expressions; it’s even been shown that micro-economies emerge within fandoms, usually via gift-giving.

It is not a stretch to characterize it as something of a simulated nationality. membership in a group greater than yourself. As one former Tumblr user and One Direction fan told me, “Fandom is a cult.”

[F]andom, being a safe space for the marginalized, is also home to a number of fantastical conversations about identity, and as a by-product of this, often hosted a significant amount of interest in activism as well. In fact, most people I spoke to shared that the first time they were exposed anything related to identity politics (especially queer identity or feminism) was on Tumblr, and almost always within the context of fandom, e.g. representation in a favorite fan property.

Tumblr became a place for people to fantasize and build upon ideas about real identities. There was an aesthetic dimension, a dimension of role play, a feeling of camaraderie with others—but it was often pure fiction.

This same pattern emerged with mental illness, and, having such a noticeable impact on teens, spawned several studies.

Tumblr’s heyday coincided with another interesting cultural shift. Media outlets were slashing budgets and, notoriously, publishing clickbait. Contributors to websites like BuzzFeed would trawl the internet looking for obscure communities to write about, magnifying trends that may not have ever been real trends at all.

Headlines from 2013 and 2014 provide a nearly endless stream about Tumblr’s new social activism, how it helped organize millennials who wanted to get involved with Black Lives Matter, how it shaped our understanding of gender…but all this seems to have been memory-holed. And so today, many of us spend much of our lives scratching our heads asking, “When did the conversation change so drastically?”

When Tumblr ruled the internet.

Fandoms—especially those coalescing around fantasy and fan fiction—and online mental-illness, are well documented in a podcast I mentioned last week, Blocked and Reported. They’re also hotbeds of intranecine cancelation, or scapegoating, within their own online communities.

I can’t help suspect that the dearth of “implicit, shared understandings,” Olivier Roy’s definition of macro-culture, has led to fandoms and other subcultures in which, as Dee notes, even “a politician” is a fair subject for fanatical idolatry.

On that note, I end with another great piece by Santiago Ramos, about the time, recounted in Jim Jarmusch’s Gimme Danger, when Iggy Pop resorted to doing summersaults, rather than endorse the grand poobah of Ann Arbor politics, the semi-ridiculous leader of the White Panthers balladized by John Lennon, John Sinclair.

Six Reasons Why Artists Should Avoid Politics

Ideas for this election season.

Santiago Ramos, Wisdom of Crowds

Have an agreeable weekend. Enjoy the disagreement.