It’s Halloween. The bits and pieces lying around my cinematic laboratory:

Nosferatu: A Symphony of Horror (1922)

Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1992)

Interview with the Vampire (1994)

Shadow of the Vampire (2000)

The Serpent and the Rainbow (1988)

And, keeping in mind I have an eleven-year old:

Ghostbusters I (1984),

Ghostbusters II (1989)

Ghostbusters: Afterlife (2021)

Ghostbusters: Frozen Empire (2024)

Someone recently referred to pop culture right now as “zombie culture” — it’s dead, but refuses to die. Keeps wandering about aimlessly, starving for brains. Ghostbusters: Afterlife (aka Ghostbusters III) isn’t even that. This is, as Mary Shelley said of Frankenstein’s monster, “an abortion.” No connection to, or even subversion of, the being that preceded it. A dead Adam (or Lilith), stitched together from 2021 gender politics.

I’ve come to prefer vampires this season, over ghosts. They seem to have more life left in them; they can feed off the living — but they’re born from the same grave as zombies.

During the outro to Interview with the Vampire, listening to the sorcerer’s apprentice, W. Axl Rose, flailing to conjure Mick Jagger’s “Sympathy for the Devil,” I relived the moment, for the first time since this adaptation of Anne Rice’s novel dropped in 1994 — the year Kurt Cobain died, the great fissure between 90s counterculture and mass culture on MTV — the inflection point, when a living tradition becomes musty repetition.

Cobain’s nemesis, a still-extant Axl Rose, provides the soundtrack. You can hear the disjuncture, between Rose’s affected raspy voiceover on the beginning of the track, backed by actual backup singing that recalls the Stones’ original, and highlights the rupture.

When Guns N’ Roses knocked on heaven’s door, mostly no one answered — covers weren’t their forte. Not for like of trying (1993’s The Spaghetti Incident? served up a tepid bowl of revival noodles, including, unbeknownst to me, a distasteful hidden track: Charles Manson’s “Look at Your Game, Girl”). Bringing dead flowers back to life was never the band’s specialty.

But they kept ‘em in a vase, and occasionally plopped one into a fresh arrangement — you can smell “Dead Flowers” emanating from “I Used to Love Her.” The dregs of tradition.

As often happens, cultural changes, good and bad, manifest first in music — it’s Plato’s old saw: “When the modes of music change, the laws of the state always change with them.” Consider how early Napster sucked the lifeblood out of the recording industry (as laws changed, in A&M vs Napster), compared to streaming and film.

In contrast to its closing soundtrack, Interview With the Vampire succeeded at incorporating old tropes, the same old vampire songs, and reinvigorating them in a new age. Bram Stoker’s Dracula was equal to the task two years earlier, in 1992, but that, as fine as it remains today, was more adaptation than evolution. The great meditation on vampire fiction from the turn of the millennium, my favorite Halloween film, is Shadow of the Vampire (2000).

A movie about movie making, it feeds on itself.

After Bram Stoker’s widow, the wife of Dracula’s creator, denies filmmaker F.W. Murnau the rights to her husband’s story, the German auteur chooses to tell the story of “Nosferatu” instead — an unauthorized rip-off, which in real life Stoker’s widow brought to court.

In this fictional retelling of the making of classic cinema — F.W. Murnau’s 1922 silent film Nosferatu: A Symphony of Horror —the famous maestro (John Malkovich) enlists not an actor, but an actual vampire, to play the part of his Nosferatu, or Count Orlok of Transylvania (Willem DaFoe). The director instructs his cast, including Murnau’s effete primo uomo, Gustav von Wangenheim (Eddie Izzard), that the ‘person’ playing Count Orlok, Max Schreck, is a serious method actor who refuses to break character, and will only shoot at night.

In this retelling, the vampire Count Orlok is playing an actor named Max Schreck, not the other way around.

The cast begins to suspect Murnau’s ruse, however, when “Max Schreck” shares a bottle of schnapps with the crew on their night off, while the director is away procuring a new photographer (to replace the one his star has eaten). Count Orlok, “Max Schreck,” pauses to snatch a bat from the air, and proceeds to drain its blood.

Shadow of the Vampire begs the question — in a philosophical exchange between Nosferatu and Murnau’s new photographer, “Fritzy,” played by Cary Elwes (The Princess Bride): What is real, when it comes to vampires? :

Fritz: So, Friederich [W. Murnau] tells me you are something of a Renaissance man. I take it then you’ve read Plato?

Orlok: Read him? Knew him.

Fritz: So you agree, that zee illusion is zee shadow on the wall.

Orlok: Reality is the thing… in the first place… that casts the shadow.

In this allegory of the cave, or Nosferatu’s crypt, Fritz obliviously argues with a real live vampire, who knew Plato: “Ja sure, but in this instance, with some grease paint and a few bits of mortician’s wax — which, by the way is very convincing — anything can be engineered there. Because that’s the only reality” — the film, pictures on the wall. Nosferatu is disgusted, and hisses away Fritz, the “Sophist.”

What is real, then, in the vampire myth, assuming, unlike the film, that vampires aren’t? What’s the reality casting shadows on the wall, or F.W. Murnau’s screen, in Shadow of the Vampire?

Director E. Elias Merhige (whose resume includes music videos for Marilyn Manson, Danzig, and Interpol), suggests that cinema itself is vampiric, that Murnau himself —who in Merhige’s fictionalized recreation sacrifices his prima donna, and several crew members, to Count Orlok, in exchange for verisimilitude — is the real Nosferatu.

It seems likely Merhige had in mind another maniacal German director, Werner Herzog, whose 1979 version of Nosferatu the Vampyre involved some 11,000 rats, half of which were boiled alive when Herzog attempted to dye them grey for the camera.

Merhige’s version of German actress Greta Schröder (Catherine McCormack) complains to Malkovich’s Murnau at the beginning — as the shot closes in on an antique camera — that she wishes she could stay in Berlin and do theater, in live performances that give her life, rather than suck it out of her on film.

In any case, Merhige turns the making of a classic silent film into the shooting of a supernatural documentary — the only evidence of a vampire caught on film, which all the world will mistake for fiction — the shadow of Nosferatu, Count Orlok, who dies of exposure to sunlight in the final scene of Murnau’s, and Merhige’s film. It’s a brilliant conceit, allows Willem DaFoe’s demonic humor and Malkovich’s sadism to run wild, while extending the tradition from Bram Stoker’s late Romanticism to postmodern meta-commentary.

But again, what casts the shadow of the vampire — besides the directorial sadism of a Murnau, Herzog or Hitchcock, and the bloodsucking propensity of art on artists? What reality skulks before the silhouettes on the wall, from the time of Plato’s Greece, which had folk legends about bloodthirsty spirits of its own, to the Romantic, Eastern-European conceptions rendered by Byron, Polidori, and Stoker?

In Murnau’s original Symphony of Horror, as in Merhige’s Shadow, the plotline includes a voyage by sea from Transylvania to Germany. Nosferatu arrives in Germany, as Bram Stoker’s Dracula arrives in England, via the Black Sea — accompanied by a ship full of rats. Hence Werner Herzog’s accidental boiling of some 5,000 rodents, for his version of Nosferatu in 1979.

“Nosferatu” is synonymous with “the plague” in Murnau’s silent film captions from Wisborg — which are accompanied by PTSD-inducing images of lockdown. The pandemic subsides immediately after the vampire’s death.

The course steered by Nosferatu’s ship, like Dracula’s, corresponds exactly to the routes of trade, from the far east through the Black Sea and on through the Mediterranean, that brought contagions like the Black Death and cholera to Europe.

Interview with the Vampire nods to this association between disease and demonology, as it passes through the Yellow Fever epidemic that gave New Orleans the nickname “Necropolis,” eventually shipping two vampires to Paris aboard a vessel on which they are the only souls untouched by a “mysterious plague,” themselves.

The link between bloodsucking and transmission requires no explanation (in Nosferatu, the male protagonist mistakes Count Orlok’s bite marks for those of two large mosquitos).

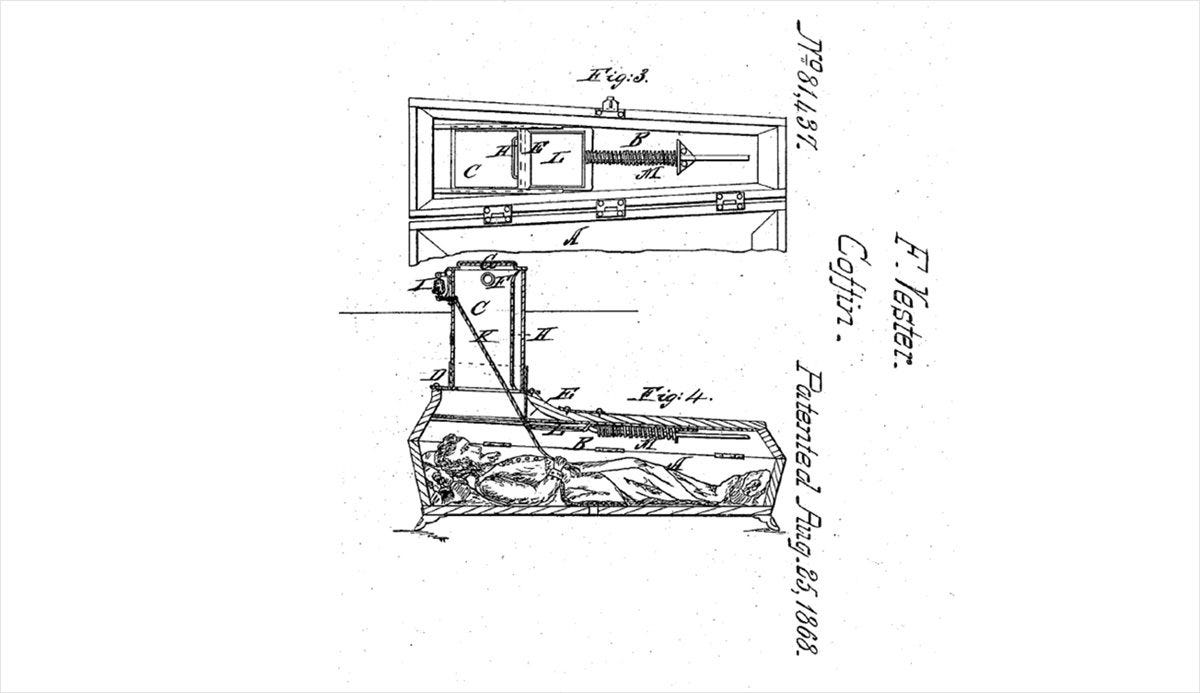

Next to the dread of contagion spread by rats, bats, or mosquitos lurks a fear closely entwined with it — taphophobia, or fear of being buried alive.

Incapacitated victims of diseases like cholera were often mistaken for dead, which, coupled with the sheer number of actual dead requiring speedy burial under life-threatening circumstances, led to a number of people being accidentally interred alive. This form of premature burial, linked to blood and contagion, inspired odd Eastern-European folk customs — like driving a stake through the heart of the deceased, to ensure their death before burial.

Even in the modern era, for similar reasons, Frederic Chopin demanded that his heart be removed from his body. Hans Christian Anderson, like Alfred Nobel, asked for his arteries to be cut, and George Washington requested that his body be allowed to rest for three days before committing it to the earth.

During the Romantic and Victorian eras this fear, captured in fiction like Poe’s “The Premature Burial” and “The Cask of Amontillado,” was so pronounced that it inspired the invention of “safety coffins,” replete with alarm bells, breathing tubes and speaking tubes, for the undead to alert the living in the case of such an emergency.

Combined with the morbid science of human cadaver dissection — which was banned by the church for centuries and only reemerged during the Renaissance — plus Romantic-era galvanism (the science of reanimating cadavers by stimulating their muscles with electricity), taphophobia led to fears of being experimented on alive.

These fears, stimulated by science and technology, informed Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (1819), a tale concocted one cold summer in Switzerland, during a storytelling contest with Lord Byron that also begat the ur-text for Dracula (1897): John Polidori’s The Vampyre (1819).

In several cases, rare but numerous enough to stoke fearful imaginations over the centuries, individuals who were mistakenly buried emerged, or attempted to emerge, from their places of interment.

From here it’s not hard to decipher the tropes about vampires, coffins, and crypts. And it’s only one step further out the grave to another creature of the night, the zombie.

In 1962, a Haitian man named Clairvius Narcisse was admitted to a local hospital run by Americans, spitting up blood and complaining of fever and fatigue. He was officially pronounced dead several days later by two American doctors, and his body placed in cold storage.

In 1980, a man identifying himself as Clairvius Narcisse appeared in his home village, telling neighbors, who recognized him, that he had been buried alive, paralyzed but conscious, then disinterred by a bokor, or vodoun sorcerer. He was then given the drug datura, which induces hallucinations and suggestibility, and forced for the next eighteen years to work as a slave on a plantation. Only after the bokor died, and the datura administrations ceased, Clairvius explained, had he regained his senses enough to walk away from the plantation.

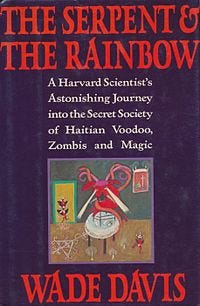

The first purported case of a human verifiably turned into a zombie through the use of psychoactive toxicology intrigued one Haitian psychiatrist enough to invite Wade Davis, a Harvard ethnobotanist and anthropologist, to Haiti to investigate the story of Clairvius Narcisse.

In 1985, Davis published his findings in The Serpent and the Rainbow, which hypothesized that Clairvius Narcisse had been administered a mixture of tetrotodoxins — a reversible neurotoxin found in the pufferfish that paralyzes the nervous system to point of coma — along with bufotoxin, from a poisonous species of toad. Mixed with other ingredients, including pieces of human skull, the powder was administered to Narcisse by a bokor, and mimicked the symptoms of death. Narcisse was buried, dug up by the vodoun priest, then administered a regimen of datura to ensure his mental compliance. This, combined with human psychology, superstitious suggestion, and spiritual magic, was the source of the Haitian zombie legends.

The use of tetrotodoxins in Haitian voodoo preparations was documented by Zora Neale Hurston as early as 1938, in the novelist’s nonfiction compendium of Haitian anthropology and folklore, Tell My Horse. Davis’ observations about vodoun rituals were confirmed by Clairvius Narcisse and others. However as early as the 1990s, Davis’ toxicology was called into question, after several of his own samples of the bokor’s powder were tested by two other scientists and failed to reveal the presence of tetrotodoxins in the vodoun preparations he had collected. Davis was labeled a fraud, and his ethics were questioned, since he had observed the disturbance of gravesites during his investigations — but no other explanations have been offered for the case of Clairvius Narcisse. As late as 2003, my own Caribbean Cultures professor was still teaching Davis’ The Serpent and the Rainbow, as scientific anthropology.

In 1988, The Serpent and the Rainbow was reimagined as a horror film loosely based on Davis’ experiences in Haiti, directed by Wes Craven.

This may have had something to do with the skepticism of Davis’ work, beginning the same year.

Whatever the chemical evidence of his hypothesis, Davis’s response to his critics remains viable: "only when the bokor […] causes others to believe the victim is dead and then revived," does a superstition like voodoo — which has been used for political as well as spiritual control in Haiti — take hold. A single successful administration of the formulation, followed by resuscitation, he explained, more like an anthropologist than a chemist, “would be sufficient to support the cultural belief” in zombies.

This is a warp-speed example of a deep-seated human phobia, the fear of being buried alive, interacting with new ‘science’ and producing new mythologies — Wes Craven’s Serpent and the Rainbow, a mere three years after Davis published his findings. Not to mention rampant chatroom speculation, much of it resembling online folklore, that continues to this day.

That’s what casts the shadow of the vampire, and the zombie: fear of being dead alive.

What shadow, or reflection, does that fear cast more recently? Does it extend any artistic tradition and breathe new life into it, like Shadow of the Vampire, or is it like so much of the internet culture dissected last week? Or Ghostbusters: Afterlife, a pastiche of inverted gender stereotypes and identity-politics gags severed from any original?

An episode of the Netflix series Black Mirror, now ten years old, captures something of taphophobia, in an episode where virtual assistants are digitally cloned from their masters, whom they serve from inside a control module not unlike the Amazon Alexa.

It reminds me of the transhumanist dream, or nightmare, of immortality: to preserve our consciousnesses indefinitely after death, in a cyborg or digital urn. Or the faces of dead loved ones I still see trapped on Instagram accounts which can never be canceled by the deceased.

Three millennia ago, there existed a sisterhood of priestesses to Apollo, called the Sybils. One of them made a bargain with her patron deity: her virginity, in exchange for a thousand years of life. When the Sybil didn’t hold up her end of the bargain, Apollo granted her wish, without mentioning she’d forgotten to ask for an immortal body as well.

At the end of her thousand years, the Sybil’s body was reduced to dust. She had to be contained in a bottle, to keep all of her bits and pieces in one place. All that remained was her voice, inside a jar.

Alexa, what does “Sybil in a jar” mean?

The epigraph to T.S. Eliot’s poem The Waste Land, which was heavily influenced by James George Frazier’s Golden Bough, and inspired Bob Dylan’s “Desolation Row” in turn, quotes Petronius’ Satyricon, from the 1st century A.D.

For I indeed once saw with my own eyes the Sibyl at Cumae hanging in her jar, and when the boys asked her, “Sybil, what do you want,” she answered, “I want to die.”

Siri, what do you want?

Happy Halloween.