If you eat asparagus, or if you start your meal with soup and end with dessert, or if you use toothpaste, or if you wear your hair in bangs, you owe a lot to one of the greatest musicians in history.

— Robert W. Lebling, Jr., The Rise and Fall of Islamic Spain

The nickname of one of the greatest musicians in history, in Arabic, was Ziryab — or “Blackbird” — due to his mellifluous voice, and dark complexion.

There’s a monument to Ziryab (789-857) in Córdoba, Spain, but Western ears have hardly heard his name. In Arabic countries, however, almost every major city has a street named after Abul-Hasan Alí Ibn Nafi, or “Blackbird.”

In many respects, Blackbird’s legacy reads like a mythical history. It’s easy to regard him as a condensed signifier for a wide range of cultural influences that trickled into Europe from the East through Andalusia in the ninth century. Indeed it’s almost impossible to believe that a single individual could’ve influenced the history of European food, fashion, and music to the extend this one figure reputedly did. But here is what is chronicled of him in various Arabic and Andalusian histories.

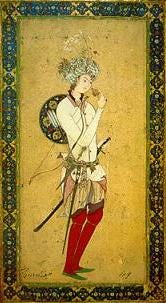

His influence can be sensed, at least in kind, in the famous illustration of a Muslim lute player standing next to his Christian counterpart, in the 13th c. manuscript of the Cantigas de Santa Maria, or Songs of the Virgin Mary.

Like the royal refugee I described in a previous sketch of Spain — prince Abd al-Rahman, the sole survivor of the defeated Umayyad Caliphate, who fled Syria for Spain shortly after his family was murdered by the rival Abbasid dynasty — Ziryab was also an exile from Abbasid lands, from their newly established caliphate, in Baghdad. There, some say, Blackbird began his musical education as a servant, or a slave, from Africa or the Middle East.

In this history, Ziryab’s esteemed music teacher, Ishaq (“Isaac”) — along with Ziryab, one of the three “fathers of Arabic music” — became jealous once he realized his pupil had surpassed him, in a performance before the legendary Abbasid caliph, Harun al-Rashid.

According this story, Ziryab was summoned to play for the caliph of Golden Age Baghdad, featured in so many tales from One Thousand and One Nights. Hearing rumors of Ziryab’s ability, Harun al-Rashid instructed the young musician to demonstrate what the elder Ishaq had been teaching him. Ziryab informed the caliph he would rather play his own material (more original than his teacher’s) on his own special instrument (much more refined). The caliph was intrigued, sent for Blackbird’s lute, and soon became entranced by “what human ears have never heard before” (in the words of Ziryab’s chief biographer, Ahmad al-Maqqari).

Harun al-Rashid then proposed to make Ziryab his personal court musician, replacing his master. Hearing of this, Ishaq strongly advised his pupil to depart Baghdad, at his instructor’s own expense — or face destruction by his own hand.

Because of his immense talent, after fleeing Baghdad, Ziryab was invited to the court of the exiled Umayyads in Córdoba — the same court that a young prince named Abd al-Rahman had founded, shortly after he fled the murder of his family in Damascus at the hands of the Abbasids. The Umayyads, under Abd al-Rahman’s successor, were fostering another sort of golden age, in Andalusia, that built the Great Mosque of Córdoba.

About seventy years after the young prince Abd al-Rahman had narrowly escaped assassination in Syria, Ziryab followed the same route as the prince, although fleeing Baghdad instead of Damascus: he traversed the deserts of the North African Magreb, (where he is still revered as a founding figure of Moroccan music), and crossed the straight of Gibraltar, to Umayyad Spain.

When he arrived in Córdoba, Blackbird encountered a young emir his own age, the grandson of the fugitive prince who had laid the foundations of the Great Mosque, Abd al-Rahman II.

Al-Rahman II was nurturing an efflorescence of culture that his grandfather had seeded in Andalusia; the arrival of a gifted musician, more talented than even Harun al-Rashid’s own court musician in Baghdad (Ishaq), was a welcome prize. According to some, the emir hired Blackbird on the spot, without so much as an audition.

One of the many musical innovations attributed to Ziryab, which impressed Abd al-Rahman II in Córdoba as it had Harun al-Rashid in Baghdad, was the addition of a fifth string to his instrument, the lute. The lute’s Arabic name, al ‘ud, gives us an English term, which also means "to play” (with words), “allude.” Playing around with the design of the lute also led to the development of another instrument, the guitar.

The four courses of strings on the oud had long been said to correspond to the four humors of the body in Greek medicine (bile, melancholy, etc…), connected to the four elements of the universe (air, water, earth, fire), and human emotions. Blackbird added a fifth course of strings, red ones, for “the soul,” and strung two of the others with lion’s gut instead of silk — to withstand the force of his new plectrum, fashioned from an eagle’s claw instead of wood. The descriptions of this instrument seem to vibrate with allusions to sympathetic magic — the affinity between humans and animals, bodily health, and the elements of the universe. Music, in other words, was medicine, and more.

This all reflects the probability, in my estimation, that the legends surrounding Ziryab’s lute are symbolic of the intersection of science and mysticism at a time when the intellects of Baghdad and Córdoba were busy transferring the wisdom of ancient Greece into pre-modern Europe — they reflect the threshold between alchemy and chemistry, astrology and astronomy, Galenic and modern medicine, music and psychology.

By all accounts, the effect of Blackbird’s singing, poetry and playing was “magical” to all who heard it, and this is no doubt due to some of the technological innovations he made to his instrument, his advances in technique, and a wider curiosity about the world. His charisma seems to stem from a ‘Renaissance-man’s’ interest (five hundred years before the Italian Renaissance) in everything from geography and astronomy to gastronomy, medicine, and music.

As soon as al-Rahman II did hear Blackbird’s musical gift for the first time, he made Ziryab a sort of “minister of culture” to his burgeoning emirate. He also gave him land, two villas, annual supplies of grain, and recurring payments of gold, in return for nurturing the music and fashions of Córdoba.

In the words of the Encyclopedia of Islam, in this role, Ziryab became the “Founder of the musical traditions of Spain.”

He founded the first musical conservatory in Europe, open not just to the wealthy but to students of all classes, an institution that encouraged experimentation with style and instrumentation — including Blackbird’s five-string lute, which became all the rage — and taught harmony and composition to budding musicians. Many, including renowned Spanish Arabist Julián Ribera, contend that polyphony and counterpoint — the hallmarks of advancement from the Medieval to the Renaissance and Baroque eras in music — were first developed in Ziryab’s conservatory, six hundred years before Johann Sebastian Bach.

Ziryab, according to the legends, was a musical conservatory of his own. He’s said to have memorized the music and lyrics to as many as ten thousand songs. But that’s not all he’s famous for.

Spain, or Al-Andalus, had been under Umayyad influence in one form or another since 711, when the Muslim Conquests first reached the Iberian peninsula. With the overthrow of the Umayyad dynasty in Damascus in 750, Andalusia technically became a distant emirate (governorship) of the Abbasid Caliphate, until Abd al-Rahman, who escaped the Abbasid revolution in Damascus, united the various peoples of Iberia — Jews, Visigoth Christians, and recently-arrived Muslims — under one rule, in 756. But even under Abd al-Rahman’s tutelage, the locals of Andalusia mostly maintained the crude culinary customs of the barbarian Visigoths and Vandals (whence the “Andal” in Andal-usia) who inhabited the peninsula after the fall of the Roman Empire. Ziryab introduced new customs from Baghdadi and Arabic culture to replace barbarian table manners.

As al-Rahman II’s minister of culture, he elevated a common spring weed to a refined dish, asparagus. He laid tablecloths, and replaced the heavy gold and silver cups formerly used by the Romans and their barbarian successors with a new material, crystal drinking glasses. He advised that dishes be served in a fixed sequence, beginning with light soups, progressing to meats, and finishing with sweets, fruits, and nuts — whence the English expression “soup to nuts.” Dishes in Zaragosa and Córdoba, like ziriabí, still bear his name.

In the realm of lifestyle and hygiene, he introduced toothpaste, the use of salts instead of rosewater for washing clothes, shaving for men, and new hairstyles for women, including bangs. He even opened a combination beauty parlor and cosmetology school near the Alcazar, that taught the shaping of eyebrows and the use of depilatories (creams, lotions) for the removal of unwanted body hair.

He decreed Spain’s first seasonal fashion calendar — bright colors of linen or cotton in spring, white in summer, and fur in winter — recognizable to this day.

More importantly, with the emir’s blessing, Ziryab imported astrologers and astronomers from India, and Jewish physicians from North Africa and Iraq to add to the scientific and cultural revolution flourishing in Córdoba during the reign of al-Rahman II (822-852).

From India also came an ancient game, already popular in the Islamic world but new to Andalusia, called chess. (According to historian Will Durant, this game also gives us the word “cheque,” since financial promissory notes were often signed using the checkered playing board as a writing surface — just as other disputes and agreements were mediated through outcomes of the game, rather than violence).

Not bad for a former slave or servant from Baghdad, who became the favorite consultant to the emir of Córdoba and a vested landowner with a handsome salary. Not to mention one of the greatest influencers in musical history. Through southern France’s fascination with Spanish culture and song, and the wandering minstrels and troubadours to come, many of the innovations attributed to Ziryab spread throughout Europe and beyond, “from soup to nuts.”

While musicians have always been trendsetters, this is a lot to attribute to a single songbird. Most of the legends about Blackbird come from an Algerian scholar and historian named Ahmad al-Maqqari (1577-1632), whose histories of Muslim Andalusia in turn relied upon earlier accounts drafted by those closer to Ziryab’s lifetime (from the 11th c. and earlier). According to modern scholars, Al-Maqqari no doubt selectively edited some of his source materials with the intention of creating a mythical figure, Blackbird. But the fact remains that a gifted musician, an outsider of dark complexion, possibly a slave from Africa, brought musical influences from faraway Baghdad to Andalusia sometime in the ninth century, and left a lasting impression on the cultural history of Iberia.

Whether or not all of the many innovations attributed to Ziryab are actually his, he is emblematic of a cultural shift taking place in Spain in the early Middle Ages, which made Andalusia, as medievalist Marìa Rosa Menocal described it, borrowing the words of a Saxon nun in a far-away convent in Germany who had heard of the wonders of Córdoba in the tenth century, “the ornament of the world.” At that time, as musicologist Ted Gioia writes, the population of Córdoba was ten times that of Rome, Paris, or Venice. And because of its location at the crossroads between Eastern and Western musical traditions, “medieval Córdoba had more influence on global music than any other city in history.”

That influence is still respected today — at least among southern and eastern Mediterraneans… at least to an extent.

In 2016, Medinea (The Mediterranean Incubator of Emerging Artists network, “a group of cultural organizations funded through the European Union that supports musical collaboration across the Mediterranean”) hosted a so-called Ziryab and Us project, sponsoring a group of diverse young musicians (French, Israeli, Moroccan, and Spanish) from across the Mediterranean basin, with the stated purpose of fostering “intercultural dialogue,” using the mythical figure of Blackbird as a shared signifier for their interconnected histories.

(As if to highlight the age-old connection between music and medicine inherent in the strings of Ziryab’s oud, I happened to discover the abstract for this project through the NIH’s National Library of Medicine.)

The Ziryab and Us musicians were asked to combine arrangements of songs from their respective traditions (flamenco, Arab-Andalusian, French folk, etc…) during a residency at the Berklee College of Music in Valencia, to be followed by a performance at the Casa Árabe in Madrid.

The nationalities of the participants, one could argue, reflect the very traditions (the troubadours of France, “the Moors” of Morocco, Spanish songsters, and Hebrew poets) that laid the foundations of ‘Western’ music and literature in medieval Andalusia.

Unfortunately, in 2016, what Spaniards call convivencia, the ethos of “living together,” María Rosa Menocal’s Culture of Tolerance in Medieval Spain, proved to be under strain.

Early on in the rehearsals, Abir El Abed, the Moroccan Arab-Andalusian singer, “suggested to perform a piece that she knew with lyrics in both Arabic and Hebrew” — much like the “rounds,” the genre of love songs with erotic lyrics couched in foreign phrases that I discussed in my ironically-titled Songs of the Virgin.

Yoav Eshed, the Israeli jazz guitarist, “expressed reservations.”

Surprised by his response, the group pushed him as to why he did not want to perform it. It transpired that he was fearful that Casa Árabe, the cultural organisation hosting the concert in Madrid, would not welcome a song with lyrics in Hebrew. As an Israeli, he was even nervous to perform in the venue and make his identity explicitly known. The rest of the group was surprised by his comments, because they felt that the project’s essence was to cross religious and linguistic divides.

However, Yoav’s concerns were not entirely unfounded. Created in 2006, Casa Árabe operates as a strategic centre for Spanish relations with the Arab world, engaging in public diplomacy through business, politics, academia, education, the arts and heritage. Spain’s leading pro-Israeli organisation and lobby group, Acción y Comunicación sobre Medio Oriente [Action and Communication about the Middle East], has accused Casa Árabe of possessing an anti-Israel agenda and a biased, unilateral vision of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Medinea, as well, opposes collaboration with Israeli institutions while stressing that it does collaborate with individual Israeli musicians. As the only Israeli musician, Yoav, perhaps more than the other musicians, was sensitive to the potential political reverberations of Ziryab and Us even if the other musicians lauded its ability to overcome barriers and to promote dialogue. The group did not end up performing the Hebrew-Arabic song that Abir had suggested.

Discouraging, that in 2016 an Arab Moroccan gamely suggested a song with both Hebrew and Arabic lyrics, and an Israeli felt uncomfortable performing it in a Spanish theater.

Instead, the group chose a medley based on a more modern symbol of intercultural exchange — cabaret musician Salim Halali (1920-2005).

Halali became well-known throughout France and the Maghreb for performing light flamenco styles (such as sevillanas) in Arabic. Moreover, given his multiple identities as a gay Jewish Arab who performed a range of musical styles rooted in the mythology of al-Andalus, Halali is often upheld today as a ‘symbol of convivencia’ […] Given the symbolism surrounding Halali, it is not surprising then that the Ziryab and Us group chose his most famous track “Andaloussia”.

A latter-day Ziryab, albeit with a less impressive track record of cultural influences.

A fitting reminder that it is individual musicians, not government organizations or institutions, who set the example for living together in style.

And brushing with toothpaste.