Ah, Venice—city of sighs and suspicious beauty. I took a romantic swim here, between the Casa Petrarca and the house of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe. Hours before the crowds arrived one morning, sometime around six o’clock.

The “House of Petrarch” is a hotel, not the father of the Italian Renaissance’s home. And the founder of German Romanticism resided in the building across the street for less than three weeks, a single autumn in 1786.

I fell into the canal between.

I was slurped into the street, is a better description. The first step looks dry, at low tide. But it’s slick and quickly leads to the second. From there it’s a short step to the third, where you get your toes wet.

Then your ankles, then your shirt and neck.

The fourth step is baptism. The bottom of the canal, which fortunately I never plumbed. Appreciate the wrought-iron spike on the way in, on step number two. It’s a jagged rusty blade, but it’s the only way out—the only real thing you can get your hands around.

True story—also an allegory. For now, let’s soak in the atmosphere of a Venetian canal (where in reality, I only spent a few seconds), to let that sink in.

Assume the house of Petrarch represents “Chivalry.” The house of Goethe, “the Romantic.” Let’s start with chivalry, which at first blush is quite strange.

Chivalry is popularly associated with knightly virtue and noble courtesy on behalf of damsels in distress. From the French word for horse—cheval.

Going back to Roman times, people who could afford horses constituted the upper bourgeoisie. By the Middle Ages, knights who could afford not only horses, but armor, became emblems of feudal nobility. This is the class of people who composed the surviving texts of one genre of chivalric romance, known as Courtly Love. A poetic tradition, based on troubadour songs.

Courting married noblewomen while their husbands were away on Crusade, and their wives were left to run the estate.

It’s probably no coincidence that the First Crusade was launched from France, where the tradition of Courtly Love proliferated and spread: in the region of Provence and the court of Aquitaine. Pieces of this curious tradition of love poetry, in fact, probably returned from the Near East along with the first crusaders.

Leslie Fiedler:

It is the essence of our culture that in it art was twice-born, poetry twice-invented, the first time in the Near East, the second in Southern France; and the living sense of that second time is preserved for us in the eleven surviving poems (one with its musical setting) by William, the ninth Duke of Aquitaine […] distinguished by his royal connections […] and his skill at seduction […].

History remembers him, however, as one of the unquestioned firsts of literature: first vernacular poet of the modern world.

And vernacular the noble Duke of Aquitaine was—speaking in the vulgar tongue, about a pair of uninhibited women:

“So much I fucked them,” William sings, “as you shall hear: One hundred and eighty-eight times, so that I almost broke my braces and my straps; and I can’t tell you what misery ensued, it was so great.”

— William of Aquitaine, translated by Leslie Fiedler.

“Chutzpah and Pudeur” (1969)

Fiedler calls this “Chutzpah”—the Yiddish word for frankness. Which he contrasts with an opposite and equal tendency in William’s poems, the desire to conceal or deny. A French word for a sense of shame or embarrassment, especially when discussing matters of a sexual or personal nature: “Pudeur.”

This pretty well sums up the evolution of “Chivalry,” from Eastern eroticism to Courtly-Love poetry cloaked in the language of gentility. A history embodied in the figure of one nobleman, William of Aquitaine.

Even in a revised edition from 1964, William’s f-bomb (fotre) still appeared as a series of dashes rather than the original verb itself—pudeur, shame on the editor.

At the end of the eleventh century, William introduced his eroticism with a disclaimer: "I will make a poem of pure nothing.”

A song of pure fancy.

“It is not about me or anybody else; it is not about love or youth, or anything else…”

Before he’s feasted with capons, refined bread, good wine, and “pepper in abundance,” by two willing maids. Then “nearly screwed to death” in a “Provençal Pornotopia,” in Fiedler’s words.

But, William assures us…

Qu’enans fo trobatz en durmen

Sobre chevaau

He has dreamt it all, “asleep and on horseback.”

As Fiedler and others have noted, before Courtly Love was idealized by the horse-and-armor crowd, there was a vernacular tradition of love poetry circulating among the itinerant and feudal lower classes, which hardly survives. Except where it was imitated by the rich and saintly.

I’ve mentioned elsewhere that around the time William of Aquitaine wrote Tan las fotei (“How many times…”) in the vernacular of Southern France, Francis of Assisi became one of the first to write down a sinful troubadour song in vernacular Italian.

Only when these sinful songs reached the upper classes were they recorded and preserved. The eleven songs of William of Aquitaine are noteworthy because they managed to survive despite being sexually licentious and suggestive of their true origins, before they were repressed and sublimated into courtly romance.

The earlier songs, as Fiedler says,

Could not have been long in existence, since the deep Middle Ages were hostile not only to the making of poems as such, but to any use of the vernacular in writing whose ends were not immediate and practical. Christianity had begun […] by attacking the “literature” of Greco-Roman civilization […] because its canon clearly constituted a kind of “Scriptures” for a rival, pagan faith. But the war of the church against, say, Ovid (who was bootlegged and preserved anyhow) was not so much a war against a poet or poets as one aimed at destroying the very concept of art which had sustained them.

A pagan conception of art which was untenable, even among the nobility of Southern France.

When “the culture of Provence was destroyed by the armies of the Church,” Fiedler observes, the “cult of Joia, of sexual pleasure, to which Provençal poetry was dedicated” was destroyed along with it—at least on the surface.

In respectable society, the cult survived in the oddly-repressed amors of Courtly Love.

A cult professing chastity while winking at adultery, encouraging the courting of married women while placing them on a pedestal like noble Virgin Marys.

Ironically (or not), it was a mother and daughter from William’s lineage, Eleanor and Marie of Aquitaine, who were credited with disseminating the values of a “Court of Love” across Europe.

This is, in part, the tradition inherited by the three poets who inspired the fourteenth-century renaissance in Italian literature—Dante, Petrarch, and Boccaccio.

About two centuries before the Italian Renaissance reached its zenith in art, it was seeded in the poems and prose of these three—derived from the songs of lowdown minstrels and the “highfalutin’ tomfoolery” of chivalric romance.

“Scriptures” for a rival pagan faith—humanism.

A few weeks ago, I mentioned that Francesco Petrarca (Petrarch)—the man who has a hotel named after him above a Venetian canal—may have first laid eyes on his muse, “Laura,” in the chapel of San Lorenzo Maggiore in Naples.

San Lorenzo is the same church where Boccaccio supposedly laid eyes on his own muse. A woman he called Fiametta, or “Little Flame.” Both “Little Flame” and Laura were thought to be married, or otherwise unattainable. A few days ago, I laid eyes on Laura in Vienna.

There was a traveling exhibit, in the Austrian capital’s Kunst museum, while I was in town: “In Love with Laura: A Mystery in Marble.”

The type of touring-sculpture show that’s deprived me of artifacts elsewhere, absent from their usual pedestals. Including one in the Kunst museum in Vienna (Leda and the Swan), and another in the Museo Nazionale in Naples (Pan and the Goat)—vacant pedestals with classical statues that were “fucking on tour!” (as my guide to Naples put it).

Encountering this exhibit in Vienna was a strange coincidence, having chased Petrarch et al across Italy—in Naples, Florence, and Venice, to little avail. It distracted me from the other masterpieces on permanent display for a couple of hours, looking for “Laura” in the Austro-Hungarian imperial art collection.

Like my baptism in Venice, what I found under Petrarch’s name in Vienna was humbling, and robbed me of a few illusions. Though the latter “Mystery Hunt” didn’t require a tetanus shot.

It was no less painful. When I found it, the exhibit quickly informed me that Petrarch didn’t lay eyes on Laura in San Lorenzo, Naples.

Not to discredit my Neapolitan guide, (who was willing to abide this misconception out of regional pride)—these things are all up in the air. The histories are subject to debate, if they exist at all.

According to the writing on the wall:

The Italian poet Francesco Petrarch (1304-1374) wrote that he first set eyes on Laura on Good Friday 1327 in a church in Avignon. When she looked at him, her gaze pierced him like one of Cupid's arrows, and he fell deeply and irrevocably in love with her. She, however, never encouraged him, remaining forever out of reach. In his celebrated poems, composed not in Latin but in the vernacular, Petrarch dwells on his life-long lovesickness.

It is generally believed that Laura was married. But did she really exist? Even Petrarch's contemporaries entertained the suspicion that he may have invented an allegorical fictional character to symbolize his ambitious pursuit of artistic fame and a poet’s crowning laurel wreath (lauro in Italian).

I knew as much, but entertained the possibility that Laura was in fact Laura de Noves of Avignon, a woman who did exist.

The wife of Count Hugues de Sade (ancestor of the French nobleman who would give his name to “sadism” in the eighteenth century, the Marquis de Sade).

This, actual Laura was a noblewoman, who died in the plague of 1348. On April 6—nineteen years to the day after Petrarch said he first met her gaze in Avignon.

The overlapping of Petrarch’s “meet-cute” story and the date of Laura’s death should be a red flag… but I’ve encountered stranger coincidences on this trip already.

Petrarch’s Canzionere (“Song Book”) includes over 300 Rime in vita Laura (“Rhymes of Laura’s Life”) and Rime in morte Laura (“Rhymes of Laura’s Death”) —implying he was inspired by someone who actually lived and died, whether he met her or not.

What I didn’t grasp was how exhaustively the myth of Laura has been copied and appropriated, even subverted, by other artists in the centuries afterward.

By the nearly-anonymous sculptor whose works were at the center of the “In Love with Laura” exhibit, for example. A man who suspiciously shares both Petrarch and Laura’s first names, one “Francesco Laurana.”

The sculptor,

Laurana died in Avignon in 1502. Like the Renaissance poet Petrarch, he had lived there for some years and moved between the South of France and Italy, which is why he may have felt a biographical affinity with the poet that inspired him to choose Petrarch's Laura as a subject for his art. Or it may have been a play on words on his own name...

Laurana produced nine busts (that we know of), only one of which bears his signature, about a century after Petrarch’s death. Three of them were in the Kunst museum.

A group of busts of women, about which we know practically nothing, forms the core of Laurana’s oevre.

How’s that for dubious origins and questionable authenticity?

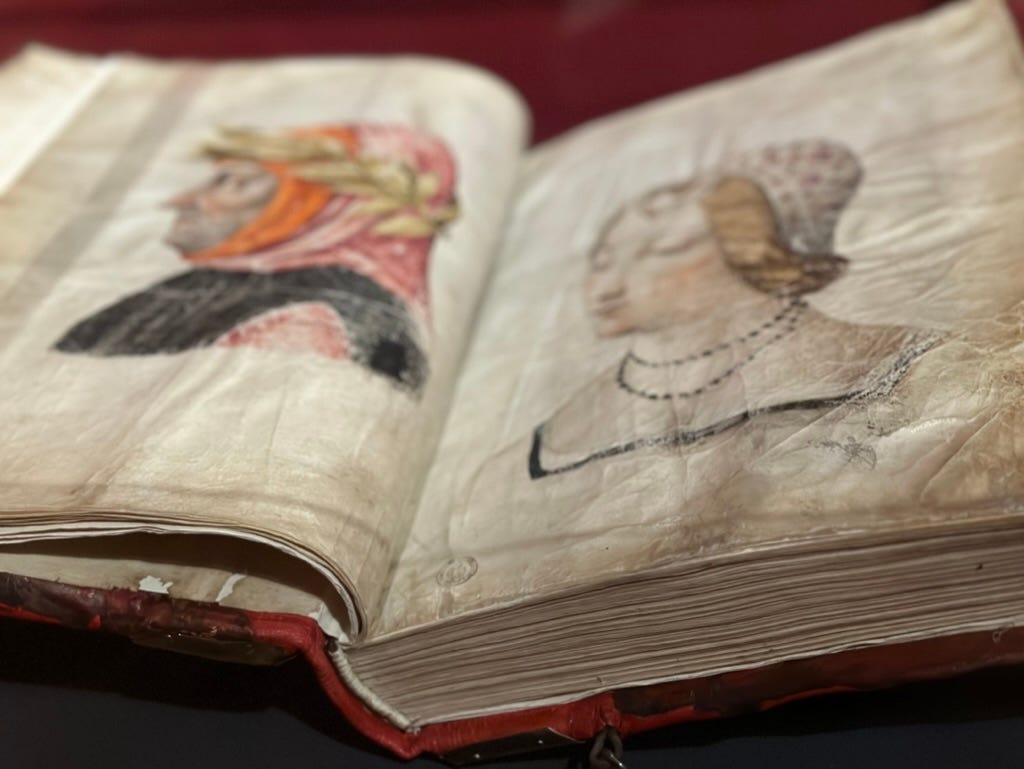

Still, they were beautiful, the statues. And they were probably inspired by images of Laura. Such as these, from a book I tried to hunt down in the Laurentian Library, in Florence (which I would have found missing, since it’s now in Vienna), with images of Petrarch and Laura—a 1463 copy of the poet’s original Canzoniere.

Petrarch’s images (above) appear to have been copied by a portraitist, in a pair of miniatures hanging upstairs in the Kunst museum’s coin collection (for some reason—cultural capital, I guess, along with images of the Beatles and Mozart in the numismatic collection). The miniatures were reproduced in blow-up form for the “Laura” exhibit downstairs. Above the books which inspired them.

As you can see, they’ve been enlarged and rearranged to suit the theme of the exhibit, gazing past one another. The orientation of the tiny portraits in the coin collection upstairs is more indicative of the relationship between these two, such as it was.

All of this is in imitation of Petrarch’s original Canzoniere “Song Book” imagery. Like Laurana’s “Laura” statue below, a copy of a copy. A reflection of a reflection, in stone.

The loving copies proliferate further still, into the era of Romanticism. In the nineteenth century, cheap plaster casts of Laurana’s original statues became popular status symbols in bourgeois homes. A copy of a copy of a copy…

Which reminds me of the infamous “Plaster Casters” of the 1960s. Groupies known for casting and collecting plaster impressions of rock stars’ … well, not their faces. (At least the 60s Plaster Casters had the chutzpah to take an impression of the Real Thing.)

Plaster casts of Laurana’s Lauras were so ubiquitous they were co-opted as feminist satire in the early 20th century.

Here, the depiction of a pregnant woman on a piece of furniture has, at it were, borrowed the face of Laurana's bust in Paris. In this drawing, the caricaturist Métivet explores the subject of abortion. 'Avoir un polichinelle dans le tiroir (to have a puppet in the drawer) is a colloquial way of alluding to someone's pregnancy. Here, the chest of drawers represents the female body, with a backstreet abortionist removing skewered puppets symbolizing unborn children from its drawers. The satirical magazine L’Assiette au Beurre was published in Paris from 1901 until 1912. It fought against social injustice and for equality of the sexes.

That’s what’s become of Laura, in the Kunst museum. Where my illusions of having visited the church where Petrarch met his muse were shattered, and replaced by a thousand others.

Petrarch’s pal Boccaccio, meanwhile, may have actually met Fiammetta inside the chapel of San Lorenzo in Naples. Or he may have met her, as he does under a pseudonym in his prose, near the Tomb of Virgil. Or she may have been a poetic device as well.

As for Dante and Beatrice, the woman who inspired The Divine Comedy… it doesn’t matter. Here’s a Beatrix for you, one of Laurana’s “Laura” Divas in Vienna:

What matters is that these characters, these half-imaginary women and their obsessive Renaissance creators in the thirteenth and fourteenth century—Dante, Petrarch, Boccaccio—helped turn vernacular Italian, as opposed to Latin, into a literary language. They wrestled the power of language from the church to the individual, from the sacred to the secular. To the extent that the church later absorbed some of Dante’s creative writing as Catholic doctrine.

The catalyst for this literary revolution, whether as poetic device or reality, was contemplating something unattainable. Whether or not Beatrice, Laura, or Little Flame existed, their authors were playing on conventions of chivalric romance that preceded them by almost two centuries: contemplating desire while celebrating restraint.

Whether or not you find this “romantic” in the modern sense of the word, it’s romance: writing in vernacular. The “romance” languages—corrupted variants of the official language of the Roman Empire and Church—that devolved into Latin vulgate and regional dialects, waiting to be refashioned by poets into the languages of nations.

A “new” literary development, a novel one in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, which wasn’t entirely new by the time “the novel” acquired its name. The vernacular narrative structure of the novel existed long before as the roman, or epic romance—stories about virtuous heroes, chaste ladies, and legendary histories.

By the time Miguel de Cervantes wrote Don Quixote in the sixteenth century, which many cite as the first early-modern novel, the author was satirizing chivalry, or romances about “knights” and nobility—"chevaliers.”

It gets confusing and more than a little Freudian, but the development of chivalry, romance, and the novel overlaps with Catholic Mariology, or worshipping the Virgin, in the songs of Courtly Love sung by royal troubadours. In certain ways, when the epic tradition met the erotic one, Courtly Love substituted the feminine, and traces of paganism, for Christian divinity.

Before court troubadours and chivalry, as I mentioned, this tradition stemmed from lewd minstrel songs from Persia, Arabia, and Asia Minor. The tradition of Courtly Love is riddled with a male “Madonna and the Whore” complex, but it has female proponents as well (such as a Eleanor and Marie of Aquitaine), and subversive interventionists.

Sculptors like Laurana may have literally objectified women, turned them into Pygmalion statuary—but there are loopholes for progress in such feverish adulation, or, as the case may be, creative posturing.

In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, especially in England, the novel was embraced by female authors, to the extent the form was derided as the “scribblings of women” by male competitors. To this day, bodice-ripper “Romances” are mostly associated with female readership.

In England, the genre of preference for many female authors was the Gothic Romance novel—tales set in the enclosed spaces of Gothic, or non-Classical-Roman structures, usually the ruins of castles or cathedrals. An architecture of confinement and horror suitable for expressing the sense of psychological confinement educated women felt in the nineteenth century. (There were women who parodied this genre as well, such as Jane Austen in Northanger Abbey, once Gothic Romance became conventionalized and ripe for satire).

By the time we get to Goethe and Romanticism—the modern Romantic movement which began in Germany and spread to England, as opposed to the proliferation of romance languages in the Middle Ages and early Renaissance—things get even more convoluted.

Romanticism was in many ways a rejection of the Age of Enlightenment and the Industrial Revolution, which was itself rooted in Classical ideals from the Renaissance. In other words, the first wave of Romantics rejected neo-Classical ideals (although second-wave English Romantics like Keats, Shelley and Byron were equally prone to obsessing over Classical Greco-Roman heritage).

Folk traditions, Grimm’s fairy tales, sublime Nature, nationalism, emotionalism, the Individual—these are the fruits of Romanticism, which sometimes overlapped with Enlightenment ideals about the individual, but were opposed to scientific rationalism, and often preferred medieval ideals to classical ones.

Gothic architecture, for example, derisively named after the “Goths” who sacked Rome, was embraced by Romanticism, and came to define Gothic Romance and horror stories like Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, or The Modern Prometheus.

A story, like the verse of Goethe’s Faust, about overstepping the bounds of nature. Goethe’s other greatest hit, The Sorrows of Young Werther, is a tale, like that of the Italians, of unrequited love. Its sensitive young protagonist, Werther, inspired a spate of imitative fashion trends and even some copycat suicides across Europe. (Goethe came to regret this youthful literary success, even denouncing Romanticism as “sick” in his later years.)

This is where we begin to approach the modern idea of the “hopeless romantic,” or the Promethean “Individual Genius,” which, I confess, was part of what brought me to the edge of that canal in Venice—a “romantic” predisposition.

Looking for solitude without the throngs of tourists, trying to get a better photo of Goethe’s house, which I just happened to stumbled upon. Thinking for a moment maybe I was standing under a building that had something to do with Petrarch, if in name only.

It’s also where medieval and early Renaissance ideals about love, chivalry and “romance” become conflated with nineteenth-century Romantic ideals about freedom, nature-over-civilization, emotion-over-rationalism, and individualism in the modern mind.

Idealism, is the common denominator. Something unattainable that doesn’t exist, maybe never will—doesn’t mean it’s not worth getting your feet wet over. Which I believe is where we left me. Drenched in humility.

If there’s anything to be said for the early Italians’ romantic obsessions, it’s an acknowledgement of the power of desire—which can be quite ridiculous.

Leslie Fiedler called it an “obsessed tone,” a “note of barely repressed hysteria,” which barely keeps it from seeming “a piece of highfalutin’ tomfoolery.”

Love is the required subject, of course, but not easy adoration or smooth sensuality[…]—rather a difficult love come on hard times, an unworthy or hopeless but irrepressible infatuation.

In my case, an infatuation with the past. A desire I learned the hard way not to fall for head-over-heels. Yet I can’t help thinking there’s a frisson of wisdom and creative impulse embedded in the Chivalric ideal of acknowledging desire while keeping it at arm’s length.

In Venice, the only thing at arm’s length was a rusty girder on the second stair. It slit my left hand open, but it allowed me to slither out of the canal under the Ponte dei Fuseri in two strokes. I wrung myself out to dry—shirt, phone, wallet, keys—grateful for the rare privacy of an early-morning Venetian back-alley. I walked around for two solitary hours, unencumbered by tourists, waiting for my shoes to stop squeaking so I could return to the hotel.

When I noticed my hand was bleeding, I wrapped it in a wet city map and nonchalantly approached the first open door I could find, a vendor just setting up for the day. Grabbed a handful of paper napkins.

A nice lady came out and gave me a mean look, then went back inside and returned with a bandaid to wrap around my thumb, once she grasped my predicament. I asked for some grappa, to cleanse the wound. She gave me vodka instead, then refused compensation. I used the last lick to cleanse my tongue.

Washed my face in a fountain running just down the street, adorned with the words of one “G.”

If Romanticism is “sick,” it takes about a week for the inoculation to run its course. By that time I was in the Kunst museum, with a tetanus shot.

Trey - you are a fabulous writer. Thank you for pix as well!