Part III: The Vampire Squid

One of the cornerstones of Jann Wenner’s optimism, which hasn’t changed much since the inception of Rolling Stone, is the improvement of society through psychedelics.

“I was doing the Joe Rogan show… promoting [my] book, and he brought up… he thought that there would be a great benefit if everyone took psychedelics,” something Wenner agrees with.

If everyone took psychedelics, “from the top down,” there would be no more greedy politicians or oil executives, no climate denial, or other societal ills. “Can you imagine, after having such an experience, seeing a homeless person on the street and not wanting to help them?,” he said to Joe Rogan.

It sounds like “pie-in-the-sky, hippie nonsense,” he admits tonight, groovy naïveté on the wavelength of Timothy Leary or Allen Ginsberg, but he believes it. It’s something to think about, along with the fact that Wenner feels comfortable mentioning his interview with Rogan.

*

There’s a soft titter at the mention of Joe Rogan, in my corner of the room. The sound of people smiling… or smirking.

I recognize the quiet condescension, having begrudged it. The same way one might recognize Wenner’s response to certain topics on the Joe Rogan show: the excusal of glaring Democratic imperfections compared to the categorical evil of Republicans; the unwavering dismissal of a New York Post story about Joe Biden; the insistence on consulting NBC or NPR during the podcast—“there, that’s the real news”—to fact check the same story.

My personal convictions, until very recently, mirrored in Wenner’s responses to Joe Rogan.

Like Neil Young, who once shared a streaming platform with Joe Rogan; like many Americans in today’s epistemological crisis, for most of the last presidency I dismissed Rogan as a misinformative dunce.

Or worse (to echo the media), as a “threat to democracy.”

It was Rogan’s interview with Alex Jones, or the coverage of that episode, that did it. And it was Rogan’s interview with Dave Chappelle that undid it, knowing the comedian had been misrepresented by the same media that often misrepresents Rogan.

When Neil Young announced he was pulling his song catalogue from Spotify over Rogan—who interviews scientists, skeptics, authors, celebrities, conspiracy nuts, human paraquats, comedians, martial arts gurus, and the founder of Rolling Stone—many were faced with the irony that an anti-conformist grunge-daddy from the pages of Rolling Stone… was now boycotting what is perhaps the closest thing to a new medium of “counterculture” in the 2020s.

The streaming equivalent of AM radio in the 1950s, a podcast show. Where one of the few voices to question the status quo sincerely, or mainstream narratives about controversial figures such as Dave Chappelle, can speak openly.

Some were forced to reevaluate Rogan, along with the status quo, and whatever “counterculture” might mean in the 2020s, after the kerfuffles over Neil Young and Dave Chappelle (Young accused Rogan of spreading COVID misinformation on Spotify; Netflix employees accused Dave Chappelle of spreading transphobia in a comedy special).

If Wenner ever harbored previous reservations about Joe Rogan, he seems to have come to a similar conclusion about the podcaster, regarding him for the most part as a benign freelancer. A good-natured inquisitor, the mutant amateur of broadcast journalism, gone pro.

*

In lengthy interviews, it becomes apparent that Rogan is a surprisingly inquisitive student of human nature. A curious interviewer, willing to sit down with anyone—whether it’s colleagues like Dave Chappelle, his pop culture hero Jann Wenner, or a uniquely troubled individual like Alex Jones—to see what makes them tick.

Presumably, that list of shiny and broken toys would’ve included Michael Jackson. In his interview with Wenner, Rogan was stunned to learn the publisher had passed up a rare opportunity to interview the King of Pop in the 90s—for Wenner, a hopeless endeavor.

The debate was whether it was possible to interview a reclusive subject like Jackson, and extract anything meaningful from a such a carefully guarded, singularly tormented individual.

Rogan thought it was worth a shot. Wenner could have intuited something about Jackson’s hidden character from the interview, printable—salable—or not.

Wenner is infamously an entrepreneur, who no doubt approached The Joe Rogan Experience, and its astronomical listenership, as a publisher promoting his book. Yet he also has a keen eye for journalistic ability—the mojo required to penetrate a subject—and evidently regards the podcaster as a capable interviewer, if not a business and publishing peer.

Much of tonight’s material, in fact, is familiar from Rogan’s three-hour podcast with Jann Wenner: Hunter S. Thompson, the social benefits of psychedelic medicine, the decrial of private wealth, the calls for government regulation of energy, emissions, and… the Internet.

The last topic offers an interesting comparison between Joe Rogan’s medium, and the volatile effect the internet has had on Jann Wenner’s—the business of publishing.

Which, as the Dean of Business already made clear in her opening remarks, is what we came here to discuss: “the intersection…of business and publishing.” That nexus, according the dean, is where we should look for urgent solutions to current social dilemmas.

*

A Dean of Journalism now opens the floor to Q&A. The first question goes to a well-heeled gentleman in the front row, whom the dean defers to by name.

“So I’m going to ask the first question,” she says in a quavery voice, “and then we’ll open it up to… Oh, Michael, would you like to ask the first question?”

The Chris Boskin Deans’ Speaker Series is named in honor of Michael’s wife, and endowed by her husband.

One gets the impression it could have easily been Michael Boskin, rather than the cousin of Greil Marcus, complaining that, “I came here to go to business school, and all we do is talk about this goddam Free Speech Movement!” Boskin earned his bachelor degree in economics from Berkeley in 1967, another business student who was here for the birth of the FSM in 1964.

That was before Boskin went on to: profess at Stanford; serve as director of ExxonMobil and Oracle; advise for Shinsei Bank and Vodafone telecommunications; and become an economic advisor to both Bushes and one Schwarzenegger.

“Counselor to presidents and governors, Boskin is one of the most prominent members of that elite group of economists who work the terrain where theory meets the real world,” according to SFGATE.

He is a go-to guy for Republicans—and, from time to time, Democrats as well—when it comes to making decisions on how the government should tax, spend and borrow. A forceful advocate of low taxes and limited government, he’s sat at the table as budgets are drafted and tax bills written.

To the shock of no one, Michael asks the Pope of Rock n’ Roll a business question.

*

Wenner has weathered recessions, inflations, the pitfalls of rapid growth, Boskin says. Does he have any economic advice for the business students in the audience tonight? (Or, you know, the students of journalism?)

After some opening remarks about starting small and surviving rapid growth, Wenner warms up to his real subject.

As Greil Marcus would later remark about this portion of the evening, for those watching it on Youtube: “The best of it comes during the Q&A at the end. Outside of Jarett Kobek’s novel I Hate the Internet, more reasoned or vehement denunciation of the internet and the rule of law you won’t have heard.”

Addressing an economics advisor to governors and presidents, an oil and internet executive seated next to a powerful influencer in broadcast journalism who consults for tech and media companies—Chris Boskin, the wife whose name is on the marquee—one gets the feeling we are working “the terrain where theory meets the real world,” right here in this room.

Wenner speaks to a literal “intersection,” or marriage of business and journalism, the power couple seated in the front row.

“I begrudge the internet,” he states candidly. “Very deeply,” and quite understandably. The internet decimated print media like Rolling Stone, “ended it, brought the end of the magazine business.” Because of the internet, he no longer has money to fund deep dives or long-form, hard-hitting journalism.

He begrudges its effect on the press and our faith in journalism.

The internet was created by the Defense Department, Wenner reminds us, “not Silicon Valley.” We paid for it with our tax dollars. “This institution belongs to the people,” not a handful of warped billionaires.

It needs to be cleaned up, taxed and regulated—a call for government intervention that elicits hums of approval in the audience.

Sure it’ll be expensive, “but they can afford another fucking billion dollars!”

And, “rule 820…maybe it’s 420…” exempts internet companies from obeying the law! “It’s reckless and it’s unnecessary and it’s destroying the public discourse. It should be brought back under the rule of law.” (Applause).

The dean moves to field the next question, but Wenner has hit his stride. “May I just, finish that question? What the internet did with all those privileges, to my business…”

As a publisher, Wenner recognizes the obvious advertising advantages of digital over print media, he says. He won’t fight technology. But, the internet “took away our income, abruptly….without conscience.” He remembers the way tech companies “used every trick in the book” to siphon the intellectual property of Rolling Stone and monetize it for themselves. These “bloodsuckers”—tech companies like Apple—have “bled dry” the very lifeblood of publications like Rolling Stone.

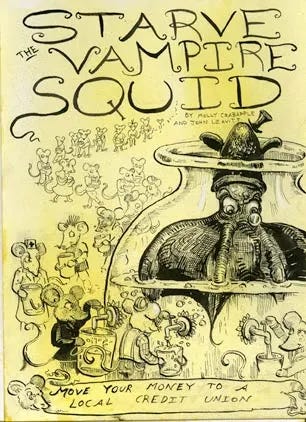

“I mean really it was like a vampire… dragon squid! With all these tentacles that had iPhones at the end of it, sucking us all dry!”

The last remark gets a lot of laughs, and more applause. It’s a nod to one of the last great writers to come out of Rolling Stone…

.Before Wenner sold his controlling share of the company in 2016, Taibbi earned a name for himself in the most famous series of articles to come out of Rolling Stone since the era of Hunter S. Thompson and Tom Wolf, covering the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis.

There, Taibbi described the world’s largest investment bank, Goldman Sachs, the way Wenner is now describing Apple—as, “a great vampire squid wrapped around the face of humanity, relentlessly jamming its blood funnel into anything that smells like money.”

Taibbi’s name is conspicuously absent from tonight’s discussion, aside from the stilted reference to his most celebrated body of work. He’s often cited, accurately or not, as the successor to Hunter Thompson.

The two share an outlaw drug history, for one thing, though Taibbi has long since cleaned up. More significantly, each writer defined an era of journalism that placed Rolling Stone in the first ranks of American publication, covering major developments outside the field of music.

Like Thompson, Taibbi also assumed the mantel of campaign trail reporter, giving candidates like Sarah Palin and Donald Trump the Nixon treatment.

Like the millennium’s catchiest metaphor for Wall Street greed (the “Vampire Squid,” now used ubiquitously by reporters covering financial fraud), the author who penned it is surely on Wenner’s mind tonight.

But Taibbi’s former editor seems to hedge a little, perhaps uncomfortable with his allusion, by embellishing the image with a personal touch: a great “vampire…dragon squid.”

Of the many attendees tickled by the thought of this hybrid creature, if any recognize Wenner’s mixed-metaphor (and surely some do), no one acknowledges the original creator.

Which is odd.

Wenner is generous about citing other quotations; he appears to distance himself from this one. “Matt Taibbi” sounds like the perfect rejoinder to Wenner’s final comment in response to Michael Boskin:

“Where is the thought journalism that’s going to tell us how to run our country, that’s going to determine what our policy should be? Sorry [about the diatribe], thank you.”

*

If Wenner is reticent, he may have a reason.

It may be because across the bay tonight, in the office where he sleeps, the eccentric new owner of one tech company is collaborating with Matt Taibbi and others on a story emerging from Twitter headquarters in San Francisco, at fiber-optic speed.

The biggest scoop of Taibbi’s career, more tentacular than Rolling Stone’s Vampire Squid on the face of humanity, and just as sucky—known as the “Twitter Files.”

Rather than breaking at a countercultural heavyweight like Rolling Stone, or Wenner Media, the story is spooling out of the social media platform itself, in a thread of tweets.

The ramifications of the #TwitterFiles leaks are then expanded and interpreted in independent newsletters and podcasts—like Taibbi’s Racket and “America This Week” with colleague

. These are hosted by yet another internet monster feeding its tentacles around traditional publishing, Substack.Perhaps the closest thing to hey-day Rolling Stone in the twenty-first century—depending on how readers curate the variety of authors on the self-publishing platform, Substack is arguably the home for “countercultural” journalism, as well as mainstream (and former mainstream) voices disillusioned with the current state of media politics.

An online orphanage, for dropouts and misfits.

And Greil Marcus.

*

Having purchased the Twitter behemoth at an inflated price, Elon Musk moved swiftly to disclose the communications records of the previous administration (“he paid 44 billion dollars to become a whistleblower at his own company,” as Taibbi said).

The CEO enlisted a handful of investigative reporters to comb through the so-called Twitter Files, and disclose them. The only condition being that reporters initially “publish” their findings on Musk’s newly-acquired app.

A subversive irony, as far as goofy tech billionaires are capable of such things: a Twitter CEO using Twitter to expose its own malfeasance.

Musk, however, has been accused of his own brand of malfeasance when it comes to “fixing” the platform, such as allegedly boosting his own Tweets, or lashing out when he disagrees with the journalists he hired to report the Twitter Files (as happened with Free Press founder

).Regardless of the CEO’s mind-state or methods, Musk has enabled an important exposé of government manipulation on social media, reported by Taibbi and other independent journalists.

*

Employing his experience as the “Vampire Squid” reporter, Taibbi—the journalist who once taught himself to translate financial fraud into plain English for Rolling Stone, is now learning to interpret the jargons of administrative Tech and State: executive Twitter-speak, and terms-of-art used by the Departments of State and Justice to interfere with the platform since 2017.

Terms like “shadow-ban” and “deamplify.” “Conspiracy” and “Mis-dis-mal-information.”

It hasn’t been pretty (due to Musk’s precondition, news is initially released in Tweet form, so readers are better off waiting for reporters to exposit in prose or podcast)—but it has been groundbreaking.

Among other things, Taibbi et al revealed that the FBI, CIA, DHS, members of congress, and a fake think tank known as Hamilton 68, have all put their thumbs on the Twitter scale, leveraging hapless Twitter execs to control the flow of information through the social media giant on its way to major news outlets.

*

The FBI wielded a particularly heavy thumb, compensating Twitter $3.4 million for its services. (It also warned Facebook about Russian interference ops that turned out to be, well, inconvenient American journalism.)

Described as the government’s “bellybutton” to Twitter, the FBI provided umbilical access to the platform for a variety of state and local actors. The Bureau’s favored modus was alerting Twitter executives to breaches of their own Terms of Service contract—breaches interpreted by the FBI and applied to accounts it deemed threatening.

Everyone from liberal actor Billy Baldwin to a Stanford Medical Professor opining (correctly, it turns out) about COVID policy—who were then deactivated, “shadow-banned,” or censored by the company’s algorithm.

By the time Taibbi and another journalist, Bari Weiss, began looking into the issue, they discovered that former FBI lawyer James Baker had been hired as Deputy General Counsel for Twitter, helping the company litigate its Terms of Service, to assist the Bureau’s “Foreign Influence Task Force”—designed to root out bad actors.

“Bad actors” like Billy Baldwin.

Unbeknownst to Musk, Baker was still on the payroll after the acquisition, still determining what records to withhold from the journalists Musk hired to investigate the company. (Baker has since been let go.)

Contemporaneous with its social media maneuvers, the Bureau was up to more traditional tricks, familiar from the days of COINTELPRO and Bush-era counter-terrorism: employing undercover agents, snitches, and good-old-fashioned shady characters.

In addition to Twitter, the FBI has made itself a nonconsensual bedfellow of far right nationalists and social justice warriors alike. As the Justice Department recently acknowledged, five agents were embedded with Oath Keeper goons prior to the Jan 6. Capitol riots. Ten out of twelve suspects in the alleged plot to kidnap Michigan governor Gretchen Whitmer have now been revealed as undercover agents. Proud Boy “chairman" Enrique Tarrio was long ago identified as a reduced-sentence informant. In February, the Intercept reported, “The FBI Paid a Violent Felon to Infiltrate Denver’s Racial Justice Movement” during the summer of 2020, recruiting a half-assed American mercenary from the Kurdish freedom fighters to encourage BLM protestors to acts of violence in the hopes of entrapment.

*

On the social media front, the impact on major news outlets downstream of the FBI’s Twitter project has been staggering. But not as staggering as the utter silence of those same news outlets in response to the Twitter Files.

Taibbi, a former darling of the #OccupyWallStreet movement, is now derided as a rightwing conspiracy theorist, Russian agent, or “threat to democracy” by the establishment left. His latest accusers include the FBI, NBC, clueless congressional Democrats, and scores of fellow journalists who repeatedly fell for the spook-doctored news sources he’s now debunking.

Which is a travesty in the oldest sense of the word: a Reversal.

An Inversion of norms.

Times have changed since the dawn of the internet, when (as Jann Wenner noted) it was the Defense Department who created the online environment, not the Departments of State and Justice. When it was the left who promoted a hands-off, freedom-of-information approach to internet regulation, while the right rattled-on about controlling freedom of speech online. When gadflies of state were promoted by liberals, not defamed.

Today, groundbreaking journalism covering shadowy government manipulation online is derided by so-called progressives in media and government, or else scrupulously ignored. Shamefully, the findings of Taibbi and other liberal journalists covering the Twitter beat are trumpeted mostly in rightwing media.

The closest thing to Hunter S. Thompson at Rolling Stone or Woodward and Bernstein at The Washington Post in the twenty-first century—the journalism of Matt Taibbi on Substack and yes, Twitter—is met with cries of heckling conspiracy. Or worse, more ominous still, with orchestrated silence…

An eerie chorus of crickets.

*

Of the few mainstream liberal voices to chirp-up in support of Taibbi’s recent reporting, Bob Woodward is one—the journalist who exposed Watergate. The other is Jeff Gerth, a veteran of the New York Times.

Gerth was recently a nonresident-fellow at the Investigative Reporting Program at Berkeley’s Graduate School of Journalism. There, he wound up debunking much of the infamous Steele dossier while conducting preliminary research for an HBO documentary, which the Investigative Reporting Program was helping to produce, Agents of Chaos (2020).

Gerth—who, incidentally, worked on the 1972 McGovern campaign while a student at Berkeley—quotes Bob Woodward in his recent autopsy of the news industry: “The Press vs the President,” a four-part article making waves in the Columbia Journalism Review.

Woodward goes on record in Gerth’s article series, urging newsrooms to “walk down the painful path of introspection” for extensively-bad reporting during the Trump-Russia era. Reporting which left readers “cheated,” Woodward said, of the kind of thought journalism now sorely missed by Jann Wenner.

Like Matt Taibbi or former Atlantic writer Walter Kirn, like former New York Times reporter Bari Weiss, Joe Rogan, or anyone else who dares to question mainstream narratives, Jeff Gerth has been largely ignored or derided by left-leaning media. With the notable exception of the CJR and and independent newsletters, Gerth’s autopsy has been taken up almost exclusively by the right.

A New York Times and Berkeley alumnus, who once worked for the same Democratic campaign that Hunter Thompson championed in Fear and Loathing on the Campaign Trail in 1972… mocked by his own.

(Ironically, the man being celebrated tonight as the tragic hero of Rolling Stone once literally, if drunkenly, embraced Tucker Carlson: Thompson gave Carlson a hug, and a souvenir pack of Dunhills, after the two dined together towards the end of Thompson’s life.)

Another shame, another travesty.

When the Washington Post comes for the man who broke Watergate, the inversion will be complete.

*

How Jann Wenner feels about this new form of thought journalism, particularly Taibbi’s Twitter-based reporting, is inscrutable.

He still regards Matt Taibbi favorably, as “a great journalist,” comparable in certain ways to Hunter S. Thompson—a purveyor of big stories woven with dark imagery and humor, as Wenner said on his episode of Joe Rogan (which aired pre-Twitter Files).

He also dismissed Taibbi’s “conspiracy theories” to Rogan—that the left is waxing as authoritarian as the right when it comes to tech and media censorship, and groupthink. One of the reasons Taibbi left Rolling Stone for Substack in 2021, five years after Jann Wenner turned the magazine over to his son.

More inscrutable still is Wenner’s vehement diatribe against the internet, in favor of Democratic politicians over and against Big Oil and Tech, effected though taxes and government regulation… addressed to a Republican economist known for promoting the opposite strategy while director of Exxon and Oracle (the company tasked with, and failing, the regulation of TikTok).

Whose wife, on the other hand, is a registered Democrat with major pull in media and publishing, a consultant to tech companies, Chris Boskin.

Mrs. Boskin is also a founding member of the Institute for Security + Technology (IST), which funds research initiatives with Orwellian names like “Geopolitics of Technology” and “Digital Cognition and Democracy.”

Initiatives which cite the founder of Hamilton 68—the dubious think tank started by former FBI agent Clint Watts, and exposed by Matt Taibbi.

Jambo mambo? “What is happening,” here? To whom is Wenner speaking—and what is he saying, if anything, between the lines?