Part IV: The Uncensored History

To understand Jann Wenner, it may be helpful to resort to a fable Greil Marcus once told, about the first time he met Wenner in the spring of 1964.

Invited to a surprisingly-comfortable perch in the hills (not far from where we’re seated tonight at the Hass School of Business), young Marcus and Wenner were getting to know one another. Grooving to Mose Allison on the hi-fi, discussing music and politics in Jann’s off-campus apartment.

Marcus, quickly impressed with Wenner’s hip acumen, was then speechless to discover a clip from the society page of the San Francisco Chronicle…

A photo of Bay Area debutantes, pinned to the wall of Jann’s room.

Here was the future counterculture journalist, an aspirant rock-n-roll publisher, the protege of jazz columnist Ralph Gleason and a denizen of San Francisco’s underground music scene, smoking joints and soon-to-be dropping Owsley Stanley’s acid…

Crashing debutante parties and collecting the write-ups. Venerating the starch-shirted blue-bloods who kept him always at arm’s length, with pin-ups.

Wenner was “a hipster and a society boy, all rolled up into one,” according to one version of Greil’s tale.

A “dope-smoking liberal on the one hand, and on the other,” there he was, “with this glint in his eye—starstruck, I guess you’d say, begging for invitations to deb parties,” as a college friend put it. Buying his own dinner jacket in the hopes of joining the fetes of the elite on their grand estates.

Jann Wenner was Jay Gatsby, an outsider always trying to make it in.

*

Wenner thrived on the outside-in. Moved and had his being, in-between worlds.

A middle-class kid from suburban Marin whose parents, once divorced, seemed to want little to do with his upbringing. A motivated lonely-child who wanted to hobnob with buttoned-up aristocrats, and meet John Lennon and Mick Jagger all at once.

Someone who spent Saturday morning skiing the Sugar Bowl resort, and Saturday evening freaking at the Longshoreman’s Hall.

Someone who moved from debutantes to rock stars and on to presidents. Who ran with Jackie O., the Kennedys, and Manhattan socialites after Rolling Stone packed up its headquarters and moved to New York.

So he beat on, boats against the current, borne back east. To East Egg and further, to zip codes more prestigious: East Hampton, home of his Montauk estate.

Running in opposite directions, a walking contradiction. Like Elvis, or Gatsby, or his pal Hunter S. Thompson.

*

There’s a hint of Wenner’s liminal position alluded to during the “Free Speech” portion of tonight’s discussion, prompted by Greil Marcus.

Jann was there—was he not, on that fateful day when police came to arrest Jack Weinberg for distributing political pamphlets on Telegraph Avenue?

When a crowd of students placed their bodies around and atop the police cruiser in protest, “sitting in?”

“And you walked out of a class and you saw that, same as I did. And you sat down…”

Marcus trailed off, as if it were a question. Well?

“I’m not sure I sat down,” Wenner clarified, “…but I hung around for a good while,” the day the Free Speech Movement was born.

*

Wenner hung around, in his unique way.

According to Rolling Stone Magazine: The Uncensored History, Jann was not only hanging around, but reporting on the Free Speech Movement, pre-Rolling Stone.

Next to one of his early articles was a photograph of Free Speech leader Mario Savio, the General Patton of the protestors, “behind a podium, addressing a massive, passionate rally… and to Savio’s left, trench-coated, with a microphone in hand, at the very edge of the action: Jann Wenner, cub reporter.”

The scene is chronicler Robert Draper’s way of illustrating Wenner’s position on the Free Speech Movement: at the periphery. A position which elicited, unfairly sometimes, bitter remarks from friends at the center of the Movement.

Wenner’s coverage of the FSM was always insightful and sympathetic, his way of being involved. Besides, by the time people like Greil Marcus’ cousin got involved, “even debutantes were marching,” according to Draper, not just radicals and misfits. If “the whole purpose of the Movement was to encourage individual expression,” as Draper says, who could blame Jann Wenner for prioritizing journalism and personal vision over the activism of the crowd?

Wenner straddled not only the threshold of middle and upper class California, or the boundary between counterculture and the establishment, he was in-and-outside the politics of the FSM.

Richard Black, a scion of the Hearst family and, as Draper says, “one of Jann’s friends from the debutante scene,” said of the future founder of Rolling Stone: “Jann Wenner had absolutely no political beliefs whatsoever,” in those days.

“He was always a paparazzo in his heart. But Jann was motivated when none of us were. He had focus. Most of us were just hanging out…” Wenner was envisioning a rock-n-roll juggernaut.

*

As Rolling Stone grew, Wenner was on a fence.

Like Wenner, the magazine he envisioned would endure a long tug-of-war between art, business and journalism on the one hand, and politics on the other, throughout its adolescent history.

One wants to sympathize with Wenner, and Marcus: much of what Rolling Stone weathered in the 1970s sounds distinctly familiar to the story of journalism in the 2020s.

*

As the sixties suffered a sudden death at the hands of the Manson family and Altamont Hells Angels, Rolling Stone established itself as an independent voice, out-scooping the majors on a number of important stories.

Its “Special Super-Duper Neat Issue” on “The Groupies” phenomenon was so popular it was copied, poorly, by Time magazine in 1969.

The same year, Rolling Stone gave the lie to mainstream narratives about the deadly concert at Altamont, which the rest of the press blithely covered as another Woodstock love-fest.

Greil Marcus reported from the foot of the stage, fearing for his life—as the biker security force worked crowd control on their motorcycles, and bludgeoned the audience with pool sticks—escaping moments before the Hells Angels murdered Meredith Hunter.

In the wake of the Manson murders, while preparing to defend Rolling Stone’s hippie demographic with the headline “Manson is Innocent,” Wenner’s reporters investigated and discovered the horrible truth instead, the dark side of the sixties dream—the fear in it—winning further plaudits for honest coverage.

Rolling Stone was the first publication to unravel the mystery of Patty Hearst’s kidnapping in 1975, trailing the heiress and her SLA captors across the country while other newsrooms speculated from their desks.

Even the feds were clueless to Hearst’s whereabouts, up to the point of her arrest on being a suspected accomplice. The mainstream media beat a path to Rolling Stone’s door, flooding its ramshackle office with television cameras to report the “Inside Story” of Patty Hearst, secondhand.

In 1972, while Dan Rather sung his praises, an esteemed trade magazine for professional journalists, the Columbia Journalism Review, credited Rolling Stone for outstanding journalism:

In a very real sense, it has spoken for—and to—an entire generation of young Americans. It has given an honest—and searching—account of one of the deepest social revolutions of our times.

*

One wants to sympathize with Wenner because, along with the shortcomings of mainstream journalism, the general zeitgeist in the 1970s was also characteristic of our times.

Part of the anxious revolutionary spirit of the early twenty-first century, in fact, probably derives from the spirit of seventies Rolling Stone. Or aspires to.

At the dawn of environmentalism, Wenner begat a satellite publication devoted to ecological issues, Earth Times. The editor he pegged to run it came to his attention, in part for announcing that, due to ecological anxiety, she would never bring a child into this world—the posture of many would-be parents today.

Earth Times failed, in part for its dedication to pessimism, running doom and gloom pieces like “The Story of Oil: Let Them Eat Ethyl” and “No One Loves a Fly.”

*

Mostly, the spirit of seventies Rolling Stone was characterized by a tension between the Art of music and letters, and Politics.

Reflected internally in the evolution of Jann Wenner, a man torn between aesthetic impulses represented by his mentor and cofounder, Ralph Gleason, on the one hand, and political impulses represented by peers on his staff, on the other… including Greil Marcus.

And always in the middle, Jan Wenner, a man fixated on the business and glamour of running a magazine.

*

Ralph Gleason, a revered jazz columnist at the San Francisco Chronicle who cofounded Rolling Stone with Wenner (and advised him to name the magazine Rolling Stone rather than “The Electric Newspaper”), was a member of an older generation, who mentored and embraced the younger.

A fondly-repeated joke about Gleason, which Wenner indulges tonight, is that at the time of Rolling Stone’s founding, Ralph was “a thirty-six-year-old who couldn’t decide if he was three twelve-year-olds, or two sixteen-year-olds.”

Young at heart, Gleason was Wenner and Marcus’ hip uncle from the bebop era, now advising the hippies. When political tremors rattled the culture, however, fissures began to show.

Gleason stood firmly in the aesthetic camp—Art over Politics.

He was fond of invoking Platonic aphorisms about the primacy of art, like “music will make the government tremble” and “When the mode of music changes, the walls of the city will shake.”

Increasingly out of tune with younger colleagues, he declared in the magazine’s pages, “Politics has failed…the Beatles started something which is beyond politics,” along with Bob Dylan. He admonished “grim, joyless anti-poetic ideologues” at Rolling Stone and elsewhere, telling readers, “The music will set you free. We know this. We have tried it and it works.”

Ralph Gleason had seen firsthand the way black music, adopted by white America, had transformed racial politics since the mid 1950s.

Greil Marcus was equally aware of the social power of music, and brought a stable of talented writers to Rolling Stone to critique it, including Lester Bangs (the critic played by Philip Seymour Hoffman in Almost Famous).

But Greil also had a political bent. As Draper describes young Marcus, the future historian had two loves: liberal politics, and Elvis Presley. He combined the two into his own curriculum at Berkeley, “American Studies,” the field in which he’s highly regarded today.

*

For many staffers, the turning point for political activism came on May 4, 1970, at Kent State. Memorialized by Neil Young: “Four dead in Ohio,” at the hands of Nixon’s National Guard.

A George Floyd moment, which Robert Draper did well to describe in 1991, a year before the riots over Rodney King.

After Kent State, “Outrage rippled across the nation…Moderates and the politically indifferent became instant protesters.” Campuses across the nation were locked-down— “trashed, boycotted, then hastily shut down by administrators for the duration of the semester.”

Rolling Stone captured the general feeling at the time with a quote from Richard Nixon on the cover: “On America 1970: A Pitiful Helpless Giant.”

There was a Tom Cotton, New York Times moment in 1970, as well.

In the summer of 2020, journalists at the New York Times demanded, and received, the ouster of their Times editor, who had published an Op-Ed by Senator Tom Cotton, “Send in the Troops,” which called for the National Guard to intervene if George Floyd protests continued to manifest violence. (An unsolicited opinion piece, not the editor’s views, it was still regarded as life-threatening by Black staffers.)

In 1970, there was a similar struggle for control of Wenner’s magazine (the only difference being that Rolling Stone employed no black writers at the time; little of their music coverage was devoted to black artists).

Furious about Kent State, and the lack of activism on behalf of certain colleagues, staffers outlined a manifesto. A list of demands and “principles to be affirmed.”

The staff would be given more authority. Ralph Gleason’s editorials elevating music over politics would no longer be condoned. Important social issues would hold sway. “Rolling Stone staffers began to speak of the magazine as theirs…In essence, Jann Wenner would cede control,” Draper reports.

Wenner would have none of this.

“We’re not the New York Times,” he admonished his employees (now surrounding him in the reception lobby). “We’re just a little rock newspaper,” he pleaded. “We’re not gonna turn into any big corporate bullshit. We’re gonna do our own thing.” He quoted the Beatles. “We have to Get Back, get back to where we once belonged.”

No more politics.

He was backpedaling, somewhat. A year earlier, Rolling Stone’s April 5 issue was dedicated to, “American Revolution 1969.” In the editorial section, Jann conceded to the revolution:

Like it or not, we have reached the point in the social, cultural, intellectual and artistic history of the United States where we are all going to be affected by politics…These new politics are about to become a part of our daily lives, and willingly or not, we are in it.

As Draper mentions, Wenner’s editorial sounds like it was written with a gun to his head. His “message to the left” had traditionally been, “Rolling Stone is mine, not yours or anyone else’s.”

That was still his message to staffers, even as he allowed the magazine to take a gradual L-turn into Berkeley politics in 1969.

*

It took the turbulence of history for Wenner to reluctantly arrive at his concession to “new politics” during the “American Revolution” of 1969… before backing off somewhat in 1970.

In response to seismic political events, more often than not, the magazine responded with pop culture coverage. As Draper points out, after the assassination of Martin Luther King, Rolling Stone published an obituary not of the civil rights leader, but of “Why Do Fools Fall in Love” singer Frankie Lymon. After the shooting of Robert Kennedy, Wenner shot down the new Cream album. In response to escalation in Vietnam, Rolling Stone turned out an article on American GI’s smoking great weed in Southeast Asia. Nixon’s election, a heartrending setback for the counterculture, was ignored in favor of John Lennon’s foreskin, in the pages of Rolling Stone.

Perhaps the political ideologues on Wenner’s staff had a point.

*

For a year or so after Kent State, Wenner adhered to Ralph Gleason’s belief that, in Draper’s words, “Manifestos were bullshit, like gathering moss.” “Kids spoke through music, not with ballots or bricks.”

Never keen on violence, Jann denounced the Yippies, led by Abbie Hoffman, for luring protestors to the Democratic Convention in Chicago in 1968—an event destined for violence.

Wenner did have foresight: Hunter S. Thompson was mentally scarred for life on the streets of Chicago, and even with a press badge, received a bully stick to the gut while politicians were safely ensconced inside the convention’s amphitheater.

Wenner was right about the Yippies as well.

Abbie Hoffman, the pied piper of protest, was a “clown,” as Wenner still laments to this day, to Joe Rogan. Someone who advocated burying your weed and letting it rot for a few days to achieve “a killer grass high,” in Hoffman’s words. An attention-seeking nuisance, whom Pete Townsend axed when he tried to commandeer the Who’s stage at Woodstock—the guitarist bludgeoned him with his instrument.

Echoing Pete Townsend and mentor Ralph Gleason, to his warning about not attending the 1968 Democratic Convention, Wenner added, “Rock and roll is the only way.”

*

A confrontation between Berkeley protesters and Governor Ronald Reagan’s National Guard was another turning point, closer to home, a year before Kent State.

“If it takes a bloodbath,” Reagan menaced, “let’s get it over with.”

Guardsmen leveled buckshot at protestors, killing one and injuring dozens more, in the skirmish over a community garden occupied by hippies on a strip of land coveted by the University, known as People’s Park.

The incident deeply disturbed staffers like Greil Marcus, and coincided with “American Revolution 1969,” the issue in which Wenner conceded to “new politics…part of our daily lives.” The notion of Wenner writing his editorial concession with a gun to his head is perhaps more than metaphorical, given the shootings at People’s Park.

Yet even after the “American Revolution” issue, the word from on high, according to one reviews editor at Rolling Stone, was still clear: “Don’t talk about the politics of a record. Just write about the music.”

*

The internal struggle in Jann Wenner’s consciousness, between politics on the one hand, and art, business and journalism on the other, was frustrating for staffers on both sides of the issue.

Gleason and Marcus both chastised Wenner for his inattentiveness to details during the conflict. At first he seemed receptive to the criticism… “But after a while he began to appear thoughtful,” Marcus said, “which is not Jann’s normal mode.”

While younger staff looked up to Marcus for his political leadership, and Gleason grew concerned about the magazine’s aesthetic mission, Wenner was preoccupied with the glamorous life of rock and roll stars. According to Draper, it seemed to Marcus that, “the boy would not be denied his rightful spot at the debutante ball of rock and roll.”

*

John Morthland, a reviewer for Rolling Stone at the time, captured the aesthetic consequences of the political turmoil: “The year 1969 has not been a very good one for rock and roll.”

At the mercy of events “bizarre beyond the imagination,” Morthland wrote, “Art suffers at the hands of Reality.”

The same could be said for the art of journalism, and Greil Marcus’ career at the magazine. The argument over the direction of Rolling Stone simmered for a month after Kent State… until the release of Bob Dylan’s Self Portrait.

Marcus penned an unflattering review of Dylan’s album (a musical example, perhaps, of Art suffering at the hands of Reality). Wenner was not amused—it was not his policy to denigrate the heroes he worshipped in the pages of his magazine; they paid the bills. Many of them were friends. The glamorous debutantes of rock and roll—Jagger, Lennon, Dylan—were sacred, and Wenner had already fired Lester Bangs for failing to write sanctimonious stories about rock stars.

His irritation over the review wasn’t helped by the political tension simmering between himself and Greil Marcus.

“To this day, Jann will say I quit,” Marcus told the Guardian in 2012. “I’ll say I was fired.”

Fortunately for Marcus, the permanent vacation from Wenner’s magazine worked out to his advantage. He used it to produce the seminal work, Mystery Train: Images of America in Rock’n’Roll Music, for which he is best known today.

Political tensions with Marcus aside, since the end of 1969, Jann Wenner had begun to accept a shift from the Art of business to the business of Politics. “If there is any hope left,” he aspired to readers, “I think that before the next two years are out, the culture we represent will make a serious effort at and succeed in taking for itself the political power it represents.”

*

One of the miracles of Rolling Stone was the rag’s ability to convert itself to riches, subverting the Scarface maxim—“First you get the money…then you get the power. ” Wenner had been adept at leveraging the magazine’s cultural capital into revenue, ever since he convinced John Lennon and Yoko Ono to appear naked on the cover in 1968, the year of Nixon’s election.

But in 1970 Wenner found himself in dire straits financially, again. Though he had taken to reimagining his “little rock and roll newspaper” as a Hearstian empire, promising stockholders, “When I take this company public, we’ll all be millionaires,” the company was hurting.

Employees watched in dismay as the owner redecorated his office and cavorted in limousines, while cutting staff and other expenditures to staunch the bleeding.

To the rescue came an unlikely angel investor. In today’s parlance, adjusted for inflation… a tech billionaire.

Max Palevsky (now known as the tech pioneer who seeded a chipmaking startup called Intel), had designed an early computer system, and formed a profitable electronics company, Scientific Data Systems. In 1969, he sold SDS to Xerox for nearly a billion dollars.

With the windfall, a computer geek from Los Angeles reinvented himself as a hip venture capitalist, a generous contributor to liberal politicians (though according to his obituary, “Palevsky later soured on politics and focused on art”).

With Rolling Stone about to face the music, ready to pay the piper to the tune of $250,000, Palevsky’s investment of $200,000 (with strings attached, in the form of stock-options) saved the magazine from ruin in 1970.

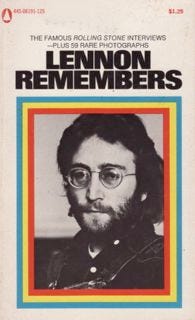

That, along with a groundbreaking interview with John Lennon, conducted by Jann Wenner. In which the frontman dished to the editor about his divorce from the Beatles, and many other juicy tidbits, for the first time in public. One of the pivotal moments in rock history: the “Lennon Remembers” exclusive.

Not content with record-breaking sales, however, Jann allowed Lennon’s interview to be put up for bid, as a book, against the Beatle’s wishes. The Beatle wrote him an angry letter:

As your company was failing (again), and as a special favor (Two Virgins was the first), I gave you an interview, which was to run one time only, with all rights belonging to me. You saw fit to publish my work, without my consent—in fact, against my wishes, having told you many times on the phone, and in writing, that I did not want a book, an album or anything else made from it.

“Two Virgins” was the nude cover of John and Yoko, which put Rolling Stone on the map and rescued it from obscurity in 1968. The 1970 “Lennon Remembers” issue (along with Max Palevsky’s tech capital), revived it a second time. Lennon was also on the cover of the first issue in 1967. You might say Wenner owed part of his success to the Beatle.

Lennon offered Wenner a chance to redeem himself—if he publicly confessed. “Print the letter, then we’ll talk,” he wrote.

Lennon never spoke to him again.

“That was one of the biggest mistakes I made,” Wenner admitted in 2017, “I chose the money over the friendship."

*

What could be done? “Print a famous foreskin and the world will beat a path to your door,” Wenner said of the “Two Virgins” cover. Print a famous interview against the wishes of that foreskin, and gain the world a second time. What profiteth a man, and a magazine…

One couldn’t always listen to conscience, nor to the John Lennons, Ralph Gleasons, or Greil Marcuses of the world—Idealists, who never considered that if Rolling Stone always took the high road, the company would’ve been bankrupt and its writers without a home. Revenue was high.

Rolling is easy, but only from the top.

*

Where is that inscrutable man of contradictory visions tonight? The man whose business sense, as his first chronicler said, “blended hippie morality with a door-to-door salesman’s flair for improvisation.”

Certainly no longer apolitical—Wenner and his magazine have endorsed Democratic politicians since the heartbreak of Nixon-McGovern in 1972.

Although there are rumors that, like most of the electorate, Wenner voted for Ronald Reagan after Rolling Stone became disillusioned with its “Rock & Roll President”—the man Wenner had boosted (then been snubbed by) in 1976, Jimmy Carter.

“Reagan has done a decent job in some ways,” Jann told Mother Jones in 1986, though he remained offended by the president’s militarism.

According to Robert Draper’s sources, former employees of Rolling Stone, Wenner voted for Reagan once, possibly twice. When discussing his falling-out with a more recent biographer, Joe Hagan in 2017, tonight Wenner denies any Reagan sympathies. If not for himself, at least for the magazine: “I said, Reagan, are you kidding me? Have you read the magazine?”

Six years before the Carter campaign, and two before McGovern’s, in 1970 Wenner was already offering what sound, in hindsight, like unintentionally Reagan-esque, even Trumpian, sentiments: “What we need is a good business executive, well-motivated, who can run the business of the country…Our foreign policy should be, ‘Let’s take care of ourselves’.”

Spoken like a proud business owner, or presidential candidate.

In 1971, on the occasion of the magazine’s fourth anniversary, Wenner announced to readers, “Rolling Stone will be a capitalist operation,” run by “businessmen and journalists.”

*

In the summer of 1974, while Rolling Stone was hemorrhaging money on a new Washington bureau, Wenner began courting D.C.’s power elite. An expensive courtship—the power-brokering, the wining-and-dining, was much to the distaste of Rolling Stone’s chief publisher at the time, Larry Daroucher.

He called Wenner “terminally starfucked,” for pinning a letter he received from conservative commentator William F. Buckley to the office bulletin board.

“You are a sham as a journalist,” the letter read, “and a failure as a human being.”

It mattered not to Wenner that Buckley was rude, or an arch-conservative—his pen pal was famous, a public intellectual.

He had a similar admiration for famous public servants.

A political correspondent for the magazine said of this era, “When Jann said politics was the rock & roll of the seventies, it was clear he thought of politicians as rock stars.”

Wenner’s dream was to consort with rock stars… if not become one.

The same year, he enthused to his financial officer after a successful board meeting, “When I see all these good people we have, it really makes me think about being President.”

*

Jann Wenner never made it to the White House, not yet. But, Draper says, he was already “in the company of presidents and popes…among the industry’s ‘power elite’,” at the age of 24.

He was invited to Time Inc.’s “Meet tomorrow’s leaders” luncheon, an invitation he snubbed—Time had poached Rolling Stone’s “Groupies” issue, after all.

He had screened the Beatles’ Let it Be in a deserted movie theater, with only John and Yoko for company, before the fallout with Lennon.

He would hobnob with the surviving Kennedys on their estate, interview every Democratic president from Carter to Obama, and shake Gorbachev’s hand. Win a National Magazine Award for his issue featuring photographs of Ronald Reagan, Barbara Jordon, and George Bush, in 1976.

A capitalist revolutionary, a hippie used-car salesman with a million dollars in the bank. A man who seldom read books, but edited and published some of the great prose stylists of the twentieth century and beyond: Tom Wolfe, Hunter Thompson, Grover Lewis, Lester Bangs, P.J. O’Rourke… Matt Taibbi.

He would play a version of himself in a Hollywood movie, with John Travolta and Jamie Lee Curtis as costars—Perfect.

The access, the power, the ability to influence—it’s all connected. You know, it’s a big voice. I want a big voice. I’ve always wanted it. And to take it away from me—I would miss it terribly. It would take me out of the center of the things I like, and that so many of my friends are connected with, which makes me more a part of their lives and in the swing of things. Like any journalist wants, desperately: to be in the middle of the action…

He said from his Montauk estate, in the summer of 1991.

*

Tonight, he is speaking to the charitable donor, Michael Boskin, who is a “go-to guy for Republicans—and, from time to time, Democrats as well,”—when it comes to making decisions on taxes and government. A consort to governors and presidents, when it comes to the regulation of wealth, climate, and the internet… to whom Wenner is decrying the various villains of all three: Republicans, Oil Execs, Tech Billionaires, etc. Which raises a host of unanswered questions, when it comes to the Pope of Rock and Roll’s response to Michael Boskin.

Is he protesting Berkeley’s wealthy benefactor, haranguing him from the stage; or working the terrain "where theory meets the real world”—trying to influence the powers that be? Hoping to effect real policy change, or sidling up to wealth and power?

Was he predicting future protests against neo-McCarthyism on the left; or more “Un-American Activities” hearings against anti-democratic Trumpists on the right… when he mused about 1960s McCarthyism struggles: “we’re gonna have them again, by the way”?

Bemoaning the internet’s effect on public discourse because his former magazine is now unrecognizable as a Free Speech organ (spending its political energy as it does, censuring Gwen Stefani for cultural appropriation, publishing editorials on “Why Cancel Culture is Good for Democracy”); or bemoaning the internet’s effect on the 2016 election, and at the Capitol on Jan. 6?

Is Matt Taibbi writing good thought journalism and policy-making reporting by airing government censorship online; or is the FBI’s manipulation of Twitter precisely the type of government regulation we need?

Subtly alluding to the Twitter Files when he applied the words “vampire squid” to tech companies; or avoiding Matt Taibbi’s name?

Is Wenner authoring his own vision, in his diatribe directed at Michael Boskin, or simply reading the room?

Having his cake, or eating it too?

The truth, if history is any indication, rides somewhere on the edge, cycling in-between. Dancing there in front of me, in the space between Chris and Michael Boskin’s chairs. In the Republican economist and the Democratic tech-and-media guru, in a marriage “at the intersection” of politics, “business and journalism.”