Any city old enough to have been occupied by Rome is at least partially “underground.” From the northern edge of the empire in say, modern Vienna, to Rome itself: the past is always trampled underfoot.

After thirty years, on my first night in the Eternal City, I descended a Roman staircase into a restaurant cellar and realized we had front-row seats in the Theater of Pompey. Our children had a similar epiphany when they went to take advantage of the tiny pool beneath our hotel: they were swimming in theater history.

Naples, “The Underground City,” takes this concept to a whole new level.

Level “negative 3,” to be precise, on what my son calls the “hell-evator.”

Thanks to its unique history, geological constitution, and the age-old tendency of its inhabitants (the little devils) to go digging through mountains and looking for portals to Hades—half of Naples and its surrounding environs seem to be connected by grottos, or “caves.”

Cisterns, aqueducts, Stygian corridors, grottos, Greco-Roman foundations, ancient communication lines, and royal escape routes, all side-by-side—an underground highway.

Like the one below, connecting the early Greek settlement of Cuma, with its ancient Sibylline oracle, to Lake Avernus, the entrance to the spiritual Underworld.

Or the Piscina Mirabilis, where all the aqueducts of the empire once drained, filling the cistern below to the ceiling with fresh drinking water, cleaned and filtered by bottom-dwelling eels. To be collected by bucket, through the holes in the roof, then transported to the Navy above. The ships of the Roman fleet waiting in the Porto Julius nearby, in Puteoli (Pozzuoli).

On its way to the “admirable pool,” the same water was used to clean the basement of the local amphitheater. A prototype for the Colosseum in Rome (don’t mention this in the capital). Superior to its Colossal cousin in at least one feat of engineering: the chambers underneath the arena were designed to be periodically flooded, to wash away the gore and animal waste following each tournament. All the gladiatorial beasts of Africa and Asia, and quite a few men, passed through the strategic military and commercial port of Puteoli, en route to the arenas of Rome. Unless they died here.

Puteoli (now Pozzuoli) and Cuma were connected to patrician villas, later affluent modern residences in historic Pausilypon, via this tunnel, the “cave of Sejanus.”

A tunnel of equal length was used by all classes, connecting the port of Pozzuoli to downtown Naples…

The passageways of the piedigrotta and the Neapolitan Crypt: half a mile of shaft-ventilated, naturally-illuminated tunnels. The Grotta Vecchia or old grotto, was dug in the 1st c. BC to improve communications between Naples and the strategically-important Phlegraean Fields, or volcanic “fields of fire” surrounding Cuma and Pozzuoli.

A network of tunnels which leads from the Tomb of Virgil, through a mountain, to what is now the Estadia di Maradona. Connecting an ancient tomb, dedicated to the poet laureate of the Augustan age, to a functional soccer stadium named after Napoli’s twentieth-century soccer god, Maradona.

The tunnels of the grotto and crypt served as functional communication routes, wide enough to accommodate an oxcart, for over 2,000 years. Portions were finally closed to the public in the early 20th century.

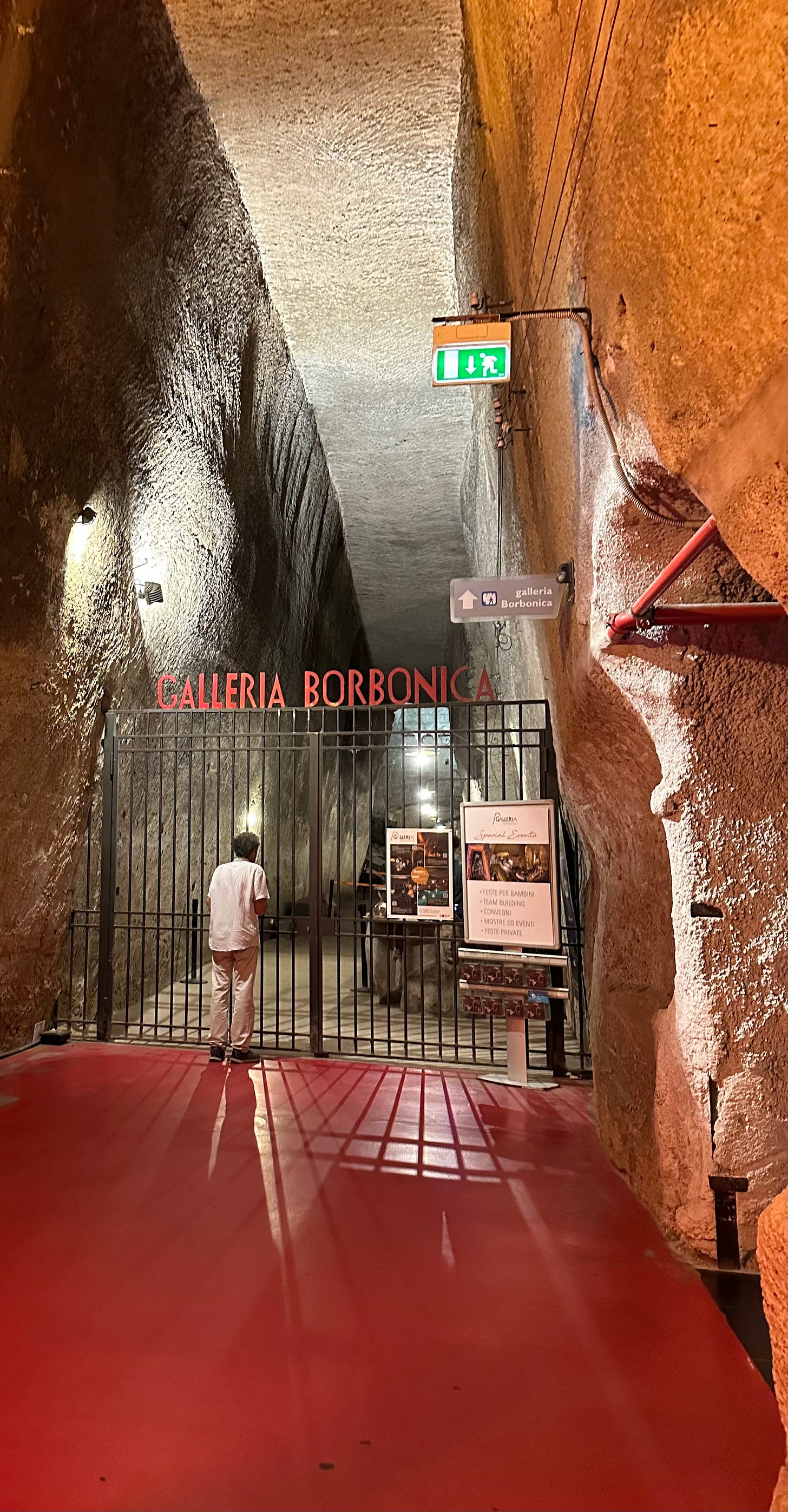

Then of course there’s the hell-evator, and the “Underground City” beneath Naples proper, still accessible from numerous entry points. We approached the underground through what I assumed was the Neapolitan version of a mall (it looks like hell, but that’s how I feel about most malls).

Before descending through a very strange ‘modern’ event space.

To arrive at the official gates of tourism, which were closed.

Fortunately our guide is friends with someone who once lived out on the streets, and now parks his car and the antiques he discovers and sells underground, who happened to be entering the expensive garage on level -3. He let us in for a self-guided tour. Afterwards he told us his story of upward (downward?) mobility, and showed us his priceless collection of pre- and post-war objects.

In the Galleria Borbonica, so-called because the final, Bourbon monarchs of Naples, outsiders from Spain, used these corridors as a royal thoroughfare. And, should the need arise, as a secret escape route. Beyond the touch of the lowly commoners.

One entrance to this subterranean network lies in the city’s historic quarter, the oldest and largest in Europe (ask any Neapolitan). Outside the doors of the Church of San Lorenzo Maggiore.

San Lorenzo itself is half-subterranean, as you can see through a section of glass floor paneling, revealing the ubiquitous foundations of a paleo-Christian church. Beneath that, a Roman market.

Above stands the church where the ribald, early-Renaissance poet Boccaccio (who unlike many of his contemporaries, loved Naples), is said to have first laid eyes on his beloved “Little Flame,” Fiammetta.

Here, or next to the Tomb of Virgil, at the entrance to the Old Grotto and Crypt—if you trust Boccaccio’s poetry.

All of this has me thinking, in light of recent revelations about Petrarch (who ended up despising Naples and donating his personal library to the city where he died, Venice), and his own myth of unrequited loved, in the person of Laura. A figure I encountered in the Kunsthistoriches Museum in Vienna.

In Naples, I was informed Petrarch met Laura in Naples. Perhaps at the Church of San Lorenzo. Perhaps Dante visited the same church?

In Vienna, I was reminded that Petrarch met Laura in papal Avignon. Or perhaps in his mind.

All the creative posturing, the copying and artifice, the suppression of erotic themes in the history of the troubadours and Courtly Love, along with the—historically speaking—elite curation of official museum content, has me convinced that much of the history of art, like religion, remains obscure or hidden.

“Underground,” if you will, in grotto.

This is essentially the thesis of cultural historian Ted Gioia, with regard to the history of the troubadours and love songs. A thesis supported, in my opinion, by the extensive history of East-West exchange chronicled in Will Durant’s The Age of Faith…

The high-minded verses of Courtly Love, with its strange Catholic idolatry of Virgins on a pedestal, originated as erotic love poetry sung by women and concubines. From the seventh century onward, this tradition made its way from Arabia, Persia, Asia Minor and North Africa, passing from Mohammedanism to Christendom on its way to Spain, Southern Italy and France. Where it was finally adopted and reinterpreted by the early innovators of vernacular Italian: Dante, Petrarch, and Boccaccio.

The history of Western song and literature is “twice-born,” in the words of critic Leslie Fiedler, the oracle of 1960s literary counterculture.

The rest is just pieced together, if not downright “fake.” In the Neapolitan sense of the word—pezzotto—which I’ll come to in a moment.

Let’s go back into the tunnels, where I’ll try to explain what I mean. Let’s start with the “underground” part.

Outside the entrance to the Old Grotto, by Virgil’s Tomb (remember this is taken verbatim from an Italian translation on a historical marker):

Throughout the Middle Ages the Crypt was surrounded by a halo of mystery and magic, with an incredible mushrooming of legends linked to the name of Virgil. According to the account contained in the "Chronicle of Parthenope" (Naples) the poet-magus created the passageway through mountain by enchantment in a single night, to help Neapolitan travellers.

In the 16 century, a bas-relief was found in the gallery depicting the god Mithras, now preserved in the National Archaeological Museum in Naples.

This has suggested the presence in the Crypt of a place dedicated to the cult of this sun god, which was widespread in late antiquity.

Worship of the god Priapus has also been suggested by some who have identified the "Grotta Vecchia" (the Old Grotto, another name for the Crypt) as the place which Petronius, the author of the Satyricon, chose as the setting of the celebration of rites in honour of this deity.

(If you’re unfamiliar with Priapus, listen closely to the list of horrific side effects rapidly disclosed at the end of your next Viagra commercial.)

The plaque outside the Old Grotto continues:

The recollection of these cults of the mysteries has been handed down in popular memory, which has always looked at the Grotto as a magical and mysterious place, and it has been related to the festa of Piedigrotta, in which the behaviour of the populace has always recalled ancient orgiastic rites. The festa was celebrated between the night of 7 September and the following day, the birthday of the Madonna. Alongside the official celebrations were the popular festivities, with decorated floats which went to the Grotto, where people danced through the night.

In Boccaccio’s day, the “festa” or carnival attendees passed from the outskirts of the city in the port of Pozzuoli, through the Grotto to arrive at the Tomb of Virgil, where celebrations took place.

This is where the poet meets a fictionalized version of “Little Flame,” according to my guide Andrea, in the verses of Il Filostrato (“laid prostrate by love”)—Boccaccio’s version of a twelfth-century Roman de Troie. A Trojan romance, inherited through medieval France, set in the grottos of Boccaccio’s Naples.

Today, though the Old Grotto is closed, it sounds like revelers travel in the opposite direction, towards the port and soccer stadium. The Estadia was forced to reduce capacity by 30,000 spectators in 1997 due to structural concerns, because fans were creating seismic tremors through the combined force of their enthusiasm.

Long before soccer hooligans and human earthquakes, carnival was associated with riotous, dangerous behavior and the suspension of normal rules. A period of sanctioned lawlessness, when the common folk could let off steam, even assuming the garb of their social superiors. An “inversion ritual,” as one theorist calls it. A Black-Sabbath parody of official church conduct, where popular folk traditions prevailed over elite spiritual ideals.

According the plaque outside the piedigrotta, it sounds like these sort of superstitious traditions—magic, sorcery, veneration of pagan poets, mystery cults—have always lurked in the tunnels, waiting to emerge. From the popular consciousness of the common man or woman, out into the streets. Or from the consciousness of elite connoisseurs into private collections or museums.

Which brings me to the “fake” part of cultural history—which is a misleading word. It’s no less fake than say, believing Virgil was a medieval sorcerer who dug a tunnel overnight. But it can be more insidious, and elitist, and I say that as someone susceptible to its charms.

Pezzotto is a new word for an old concept. I learned it from my Neapolitan guide, Andrea, while we were in the underground. Discoursing several hundred meters below the city surface.

Loosely translated, it means “fake.”

“Ah—fugazi?” I offered the Italian-American equivalent. A false one, it turns out, gleaned from Hollywood and popular music.

Andrea hasn’t seen Donnie Brasco, apparently, or heard of this word, fugazi. “Fake” is a misleading translation anyway.

He gave a fuller explanation, which is quite different. Wrote it down in capital letters, so I wouldn’t forget. One of those perfect Neapolitanisms, indicative of local character.

“PEZZOTTO” :

SOMETHING NOT ORIGINAL

PIECED TOGETHER

SOMETIMES FUNCTIONAL

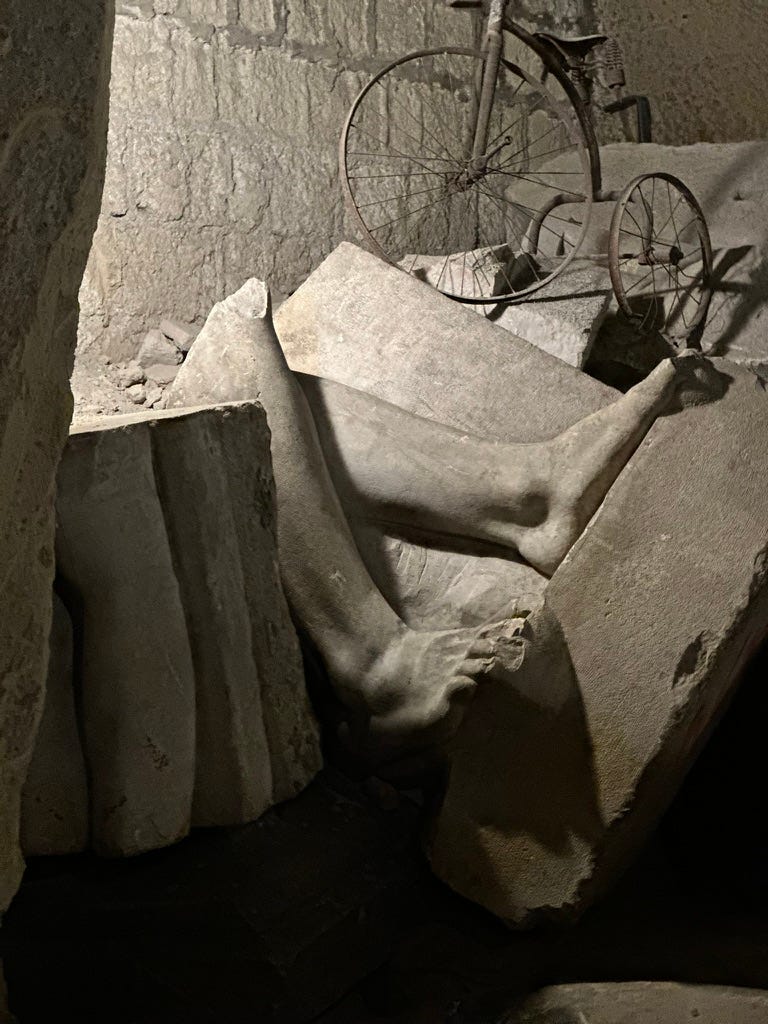

We were gazing at this marvel of engineering, in the Underground City. A product of improvisation, while the ancient system of grottos was being repurposed, under extreme duress.

A mechanical centaur. Half motorcycle, half reefer-box. Pezzotto. Fake isn’t exactly the word. It was all too real, and despite Andrea’s definition, wholly original, if cobbled together from pre-extant parts.

Like London’s modern subway system, the ancient tunnels of Naples served as a mass air-raid shelter during World War II. A subterranean sanctuary, servicing the first Italian city to revolt against both homegrown fascists and Nazi occupiers, in the grass-roots popular uprising known as the Four Days of Naples, in 1943. When the Allies finally landed, they didn’t know what to expect, friend or foe. They found the city had mostly liberated itself.

Afterward, the tunnels became a scrap yard for used parts. The post-war pieces of pezzotti to come.

I’d call this bricolage, the word Claude Levi-Strauss applied to myth. A hodgepodge of bric-a-brac components, reassembled into something new and useful—to whomever fashioned it, at least.

Bricolage, in art or literature, is the construction or creation of something using a variety of available materials and found objects. This, I think, is closer to the full meaning of pizzatto.

“A patchwork” quilt. A “rag rug.”

Here’s a more distinguished example, from the Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Napoli (MANN):

Hercules. A greater image of strength, unity, and functionality is hard to find—this one happens to be ten feet tall. The Habsburgs adorned much of royal Vienna with neoclassical images of this ancient strongman, as an emblem of State. Likewise, the family of popes and cardinals who excavated and preserved this statue would tie their cultural and genealogical history to Hercules (pezzotto!).

In this context, the hero appears a little less reliable, or original.

In the scene above, he’s twice tricked Atlas into performing his labors: stealing those three apples he’s hiding behind his back from Atlas’ daughters, and the serpent guarding the tree. He’s also just conned Atlas into taking the weight of the world on his shoulders a second time. (“Here, hold this for a second while I adjust the straps. Careful you don’t drop it—later.”)

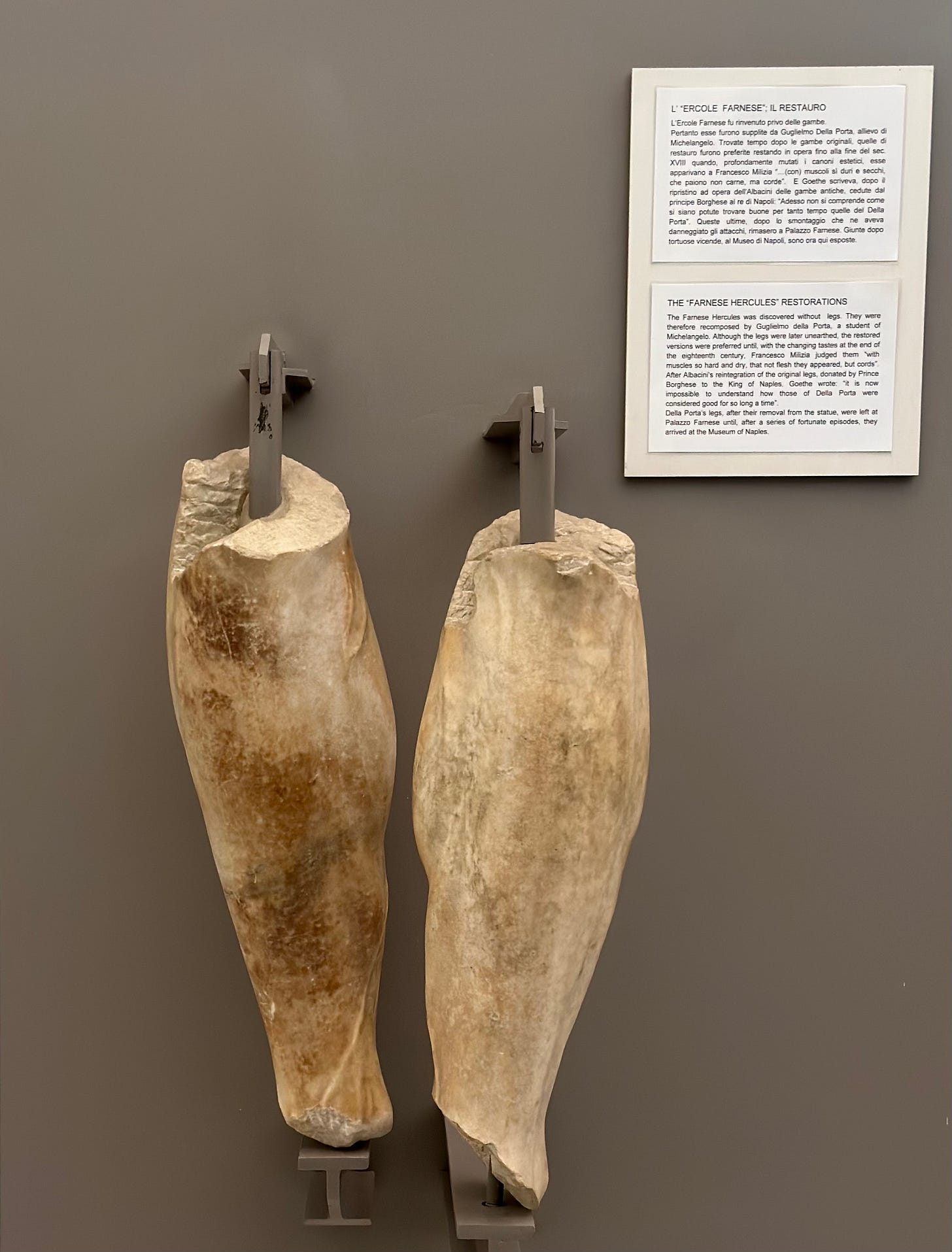

Mythology aside, Hercules at rest (the Farnese Hercules) is a Roman copy of a Greek original. For two centuries, the hero didn’t have a leg to stand on. He stood on a pair of pezzotti.

The Farnese Hercules—named after the family that produced Pope Paul III, a key patron of the Roman Renaissance—the ten-foot sculpture now exhibited in Naples, was unearthed in Rome, without legs.

Paul III was excavating materials for the construction of St. Peter’s basilica, the navel of Christendom, when his workers stumbled across what’s now considered a masterpiece of classical statuary. The Pope behind much of the Renaissance was all too happy to add a colossal Hercules to his pagan art collection.

A pair of prosthetic limbs was constructed, by a student of Michelangelo—Paul III’s chief architect, the designer behind much of St. Peter’s basilica and the Sistine Chapel—an apprentice named Della Porta.

For about two hundred years, long after Hercules’ original legs were unearthed, Della Porta’s recreations were preferred. By the Pope, by the Farnese dynasty, and just about everyone else—anyone swayed by papal opinion from the mid-fifteenth century onward.

It’s good to be the Pope.

Aesthetic tastes finally changed towards the end of the eighteenth century, several decades after the extinction of the main Farnese family line in the 1730s. A critic deemed Della Porta’s legs “so hard and dry, that not flesh they appeared, but cords.”

Describing how Hercules got his legs back, around the turn of the nineteenth century, Goethe mused:

…it is now impossible to understand how those of Della Porta were considered good for so long a time.

It depends who’s supporting those legs supporting Hercules.

In the 1450s, it was the Farnese clan of Paul III. By the 1730s, it was the Bourbons, who had come to rule the Kingdom of Naples and Sicily, along with much of France and Spain.

Thanks to the intricacies of royal intermarriage and dynastic succession, with the withering of the Farnese family line in 1731, their vast ancient art collection, which for centuries had been used to buttress the family’s image of power and sophistication in Rome, passed from Elizabeth Farnese, Queen of Spain, to her son Charles of Bourbon, the new King of Naples.

Charles’s successor, Ferdinand IV, then undertook an elaborate diplomatic effort to export the collections from the Farnese properties in Rome, which the new Neapolitan monarchy hoped to incorporate into the royal collections to bolster their ever-growing prestige in Europe.

—MANN, The Guide

Just as the Farnese had used its classical art collection to bolster the family’s ever-growing prestige in the mid-fifteenth-century Papal States.

Just as Caracalla, the Roman emperor, had commissioned these colossal copies of ancient Greek statues in the early 3rd c. AD—to impress the Roman public with the emperor’s prestige, when they adorned the site of Caracalla’s public baths. Where Pope Paul III would dig them up some 1200 years later.

Between 1786 and 1800, the Roman Farnese collections were moved to Naples and, combined with the “Vesuvian collection”—the artifacts first systematically excavated from local sites like Herculaneum (1738) and Pompeii (1748)—formed one of the largest, most renowned collections of ancient statuary in the world.

It also created an institution to house these artifacts in 1816, and boost Bourbon prestige. The Real Museo Borbonico (Royal Bourbon Museum)—the future national museum of archeology in Naples (MANN).

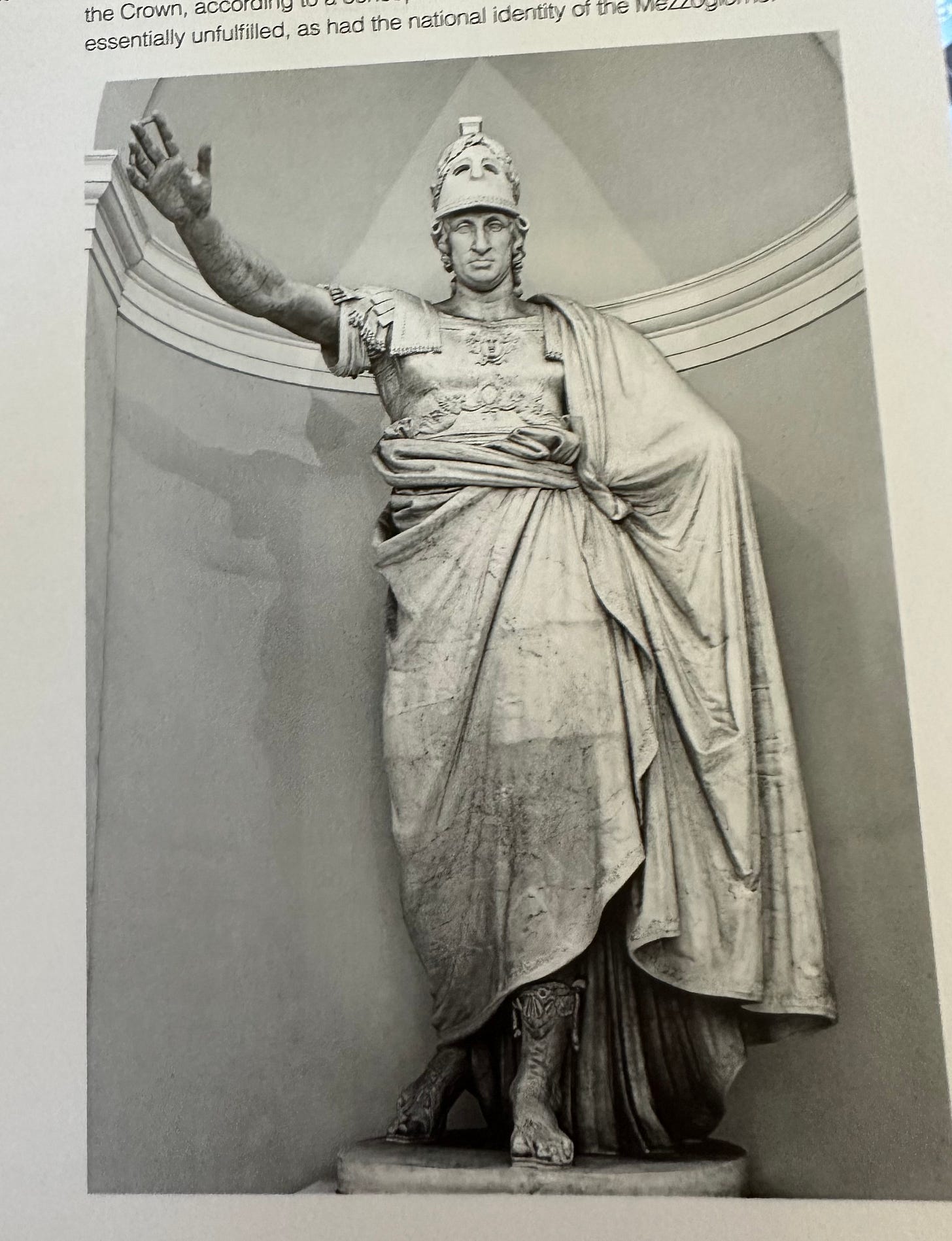

The Royal Bourbons created some interesting pezzotti of their own, despite restoring Hercules’ real legs. Here’s the head of the Bourbon king most responsible for transferring the Farnese collection to Naples, resting atop the body of the Roman Goddess of Wisdom.

On their way to constituting the core of the National Museum in Naples, the Farnese and Vesuvius collections, first housed in the Royal Bourbon Museum, were used to foster Italian national identity during the Risorgimento (the national unification of Italy, 1848-1871), and to support the main propaganda machine upheld by the archeology of the Fascista regime in the 1930s, which celebrated the 2000-year anniversary of Caesar Augustus’ birthday in 1937.

One can easily imagine Benito Mussolini’s head atop Athena-Minerva. Or the body of Caesar Augustus or Marcus Aurelius.

Or maybe here, after his fall from power.

Where the head of one tyrant (some say Achilles, abducting the young prince of Troy slung over his shoulder), has been replaced with the head of another: mean Emperor Commodus.

In any museum, any cathedral, half of what you see has likely been cobbled together from various pieces—a nose here, finger there—repainted or restored since its inception. Nothing past a certain age is completely “real” or original.

Refreshingly, I learned much of this from one of my favorite guides (besides Andrea; a woman named “rebirth” in Rome; and a pair of Austrians, a vintner and an art restorer)—the National Museum itself.

From a book named “la guida”:

Gone are the days (one can hope) of museum collections varnishing the official image of papal, royal, or state power. The Guide book offers a self-reflexive and critical account of the role museums play in fashioning these images, having struggled with conflicting narratives about the past for over two centuries of administration, both liberal and reactionary.

La Guida also reveals as much about the nature of museums in general, as Aphrodite (also from the Pope’s collection) reveals of herself on the cover.

The reason I was forced to go looking for tiny portraits of Petrarch and Laura in the coin collection of Vienna’s Kunst museum, for example. And why I discovered images of modern celebrities like the Beatles and Mozart when I reached the numismatics section.

Coins were often the only images available for connecting literary descriptions of ancient celebrities to a name and face. They were also the most-widely circulated. Sort of like album covers.

Antiquarians dedicated their entire existence seeking to give a face to these “celebrities” of the past who so dominated the collective imagination, studying countless texts and other materials, primarily from two distinct categories of antiquities collections—coins (see Numismatic Collection) and gems (see Farnese Gems).

An anonymous Roman statue excavated by the Farnese family, for example, was often given an identity based on the images found on such treasures. Just as often, false identities were misattributed to suit the purposes of the Farnese elite, “which explains the practice of affixing false [inscriptions to unlabeled statues] to substantiate a given, desired identity.”

Surrounded by modern frescoes of the Farnese family painted by Renaissance masters on the walls, a classical statue of someone arbitrarily deemed to be Alexander or Hercules, Athena or Augustus, linked the Pope’s family to the pagan heroes who proceeded them.

In this, the family of the Pope was merely emulating their Roman predecessors, who were fawning over Greeks instead of Romans.

At other times […] the inscriptions are original, carved in Roman times on portraits of celebrated Greek politicians, philosophers and writers. Such pieces were produced specifically for the Roman elites, who were steeped in Hellenic culture and anxious to acquire Greek portraits to decorate their homes.

What this amounts to is nothing less than a cult of Hellenic antiquity, that began in Roman antiquity—a weird sort of syncretic cultural religion fostered by none other than the family of the Pope himself, which I’ve been calling “humanism.”

It is that—veneration of the past, of human connection, the frailty and mystery of life—but it’s also tied to a quest for status, driven by exoticism and prurient interests, that began during the Renaissance and reached peak fervor in the eras of neoclassical Enlightenment and Romanticism to come.

In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, when National Museums were founded, and scientific excavations in the shadow of Mt. Vesuvius produced new treasure troves of antiquities waiting to be vampirized, fetishized and collected by the courts and newly-minted nation-states of Europe.

Next week, I’ll explain how these same impulses—exoticism, mystery, a quest for social mobility and enlightenment—provided a welcome outlet for the rest of society, including serfs and slaves. Going back to the time when many of the artifacts now collected in the national museums of Europe were being used and manufactured, in places like Pompeii and Herculaneum.

And—why foreign Mystery Cults exerted such a strong pull on the popular imagination, low and high.

It’s not the orgies.

It’s something unoriginal. Pieced together. Sometimes functional. Created out of sight. Grotto pezzotto.