They must tell you the truth in steps, otherwise you cannot accept it.

—La Guida

La guida is “the guide.”

Odysseus had guides, in the myths of Homer. Aeneas had the Sybil, in Virgil’s Aeneid, his Roman imitation of the Greek Odyssey. Dante’s Italian guida was Virgil, in The Inferno. Mine was named Andrea, in the Underground City.

He lit a volcano with a joint, for Rick Steves. Once upon a time.

Mystery is initiation. The nature of life and mortality, human nature, must be revealed in stages. To swallow it at all at once is indigestible. Awful and terrific.

Sad and beautiful.

We tell our children small lies about the truth, in stories and legends. Santa Claus, the Easter Bunny. We tell ourselves as well, while we slowly recall, or forget, their origins.

Symbols of what is real but unspoken.

Death and vegetables, rebirth. Blood and sacrifice. Resurrection. Connections between people, and the world.

Many mystery cults, in Greece. Initiations in Italy. Cults across the world. This is one step in mine.

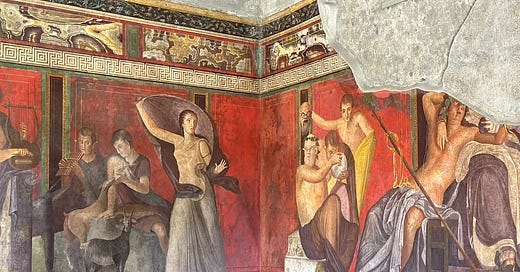

In Pompeii, outside Naples, inside a villa. On the walls of the Villa dei Misteri, or House of the Mysteries, the sacred rites of Dionysus are depicted—taboo. Such rituals were penalized by death, in turbulent 1st c. BC-AD Rome, by decree of the emperor.

Too subversive.

Beyond the long arm of of the law, legal or not by state decree, the rituals were always secret to begin with. From Athens to the Orient. Not to be told. Let alone frescoed.

Yet here they are in a former Julian villa (the dynasty of Caesars who criminalized such cults)—in a house inhabited by freed slaves. In beautiful succession. Perfectly preserved, immortalized by destruction—the petrifying ashes of Mt. Vesuvius in 79 AD.

This is one corner of a large room.

There’s an important piece missing, in the architecture and this story, which will remain un-shown. Or told.

I like this corner because it reflects something a friend said in the Villa (if you look closely), and I knew to be true.

The Guide:

“All religion begins with music.”

In Greek, in Hebrew, in Persian. All cultures. In the Book of John, “In the beginning was the Word.”

Andrea (la guida) described the fresco in historical poetry, as I recorded him. Half-way through his unique soliloquy, I noticed the camera wasn’t rolling.

Probably for the best. I remember what he said inside, and wrote down something he mentioned on the way out. “Poetry is a need”—for him, beginning at age 15, to process love.

For anyone, in it’s various forms, to process life, condensed in music—whatever inspires you. A thousand-thousand years in Words.

Mystery is initiation—segreto. Half of Pompeii is housed miles from the ancient city, in modern Naples. In the National Museum. Untrammeled by the crowds of Pompeii.

Inside the museums, infinity is going up on trial. Voices echo, this is what salvation must be like after a while.

The profanest “secrets” of Pompeii—not necessarily profane, but beautiful—remained locked in the “Gabinetto segreto,” behind the gates above. Viewed only by royalty and decadent aristocrats, until it was finally opened to the public in 1968.

(Auspicious year, that. For music and culture.)

Few are prepared for the forbidden room.

This Cabinet of Secrets has little, but something, to do with the fresco rituals depicted in the Villa of the Mysteries.

Most are merely comical, the forbidden contents of the museum cookie jar. Others are freakish. The most bestial display, normally inside, was missing the day we visited.

He’s “Fucking on tour,” Andrea joked about the infamous statue of Pan and the Goat—on loan for exhibition in Germany.

An empty pedestal in Naples.

Certain contents beyond the gate of the Gabinetto segretto in the National Museum are indeed sacred, or related to the sacred.

Thin line, sacred or profane. One defines the other. Watch your step on the way in.

Initiation rites, no matter the cult, are closely kept. For some reason, two brothers, former Roman slaves, dared to depict these rituals on their Villa walls in Pompeii, in fresh paint, after they became successful tenders of the olive and vine.

Perhaps they dared depict these secret rituals incognito, in disguise. They represent a innocent wedding banquet, according to one unimaginative historian. An encrypted death and fertility procession, says another.

They represent everything.

That’s the end of that story, for now.

Where I left Andrea, in the excavated ashes of Vesuvius, at the gate. A side exit to Pompeii. Where my son was happily waiting in the air conditioned car, while we discussed human philosophy and mythical history for a few moments. Before slowly stepping towards my ride to Rome.

I found myself a true guida. A translator and oracle.

Let us return to our beginning.

The first place Andrea took my son and self, was the Castel dell’Ovo. Across the street from the Hotel Vesuvio.

I’d researched the legend behind the name of Castel dell’Ovo, but Andrea tells it better.

The Egg Castle yarn.

And the humanitarian ethos behind mythology and oral tradition.

“On that island, you see the Castel?”

Beneath that castle, is a basement. In the basement, is a cage. Inside the cage, a box. Inside the box is a jar.

Before the year zero, a Roman poet named Virgil placed an egg inside the jar. They say as long as the egg is safe, so is Napoli.

According to medieval legend. Which made a Christian prophet out of a pagan poet—because Virgil mentioned something like the Messiah, in his verse. Virgil’s characters adorn the roof of the Sistine Chapel, and Raphael’s “School of Athens” inside the Vatican’s Apostolic Palace. Other pagan revelations reside in the Vatican Museum, in shades of marble, porphyry and stone.

Virgil’s bones are said to be buried inside the Castle of the Egg, along with his mythical Ovum. His remains can also be found at the Tomb of Virgil. Which Andrea assures me is not the real tomb of Virgil.

It doesn’t matter. The castle stands, as do Virgil’s stories, as does the island beneath, as does Naples.

That island has stood many stories, beginning with the history of Megaride. The isle, now a tiny peninsula, where Greek colonists first landed in Naples. After they made their earliest excursions into the western Mediterranean, outside their eastern Aegean home in Greece, to settle in fertile Cuma. (Towards the right, northern edge of the Bay of Naples, opposite Mt. Vesuvio on the sinister side, to the south below).

I’ve been on an odyssey to Cuma all my life. Ever since I heard the legends of Aeneas and the Sybil, told by Virgil and others.

Before I heard the stories, I realized after Naples. Breaking bread and taking wine one afternoon outside of Rome. Since I was a boy my son’s age, and sat in a restaurant named after the prophetess of Cuma. A restaurant on the grounds of the Temple of Vesta, on the outskirts of Rome. Home of the Vestal Virgins, secluded priestesses like herself, who later became nuns, as the temple became a church.

The Sybil was seeded, I now think, in my mother’s favorite restaurant, La Sibilla. Implanted long ago. Thirty trips around the sun. We were headed to Cuma later that day in Naples, it turned out, one earthly rotation ahead of schedule. To watch them sprout.

We were improvising. “We make our own story,” Andrea said, “You tell me what you like to hear. What interests you?”

La guida already knew what I wanted to hear. He was inquisitive about the ensuing generation. My son’s.

“Arri-son, what do you like?”

Ferrari. Lamborghinis. Fast cars.

To my still ruins and old myths.

Andrea explained that when the Greeks landed in front of Naples on the tiny isle of Megaride, now a fishing village and castle connected by peninsula to a seaside street called Partenopei in front of our hotel, the mariners arrived with many tales. Embellished sailor stories. The wind-blown Hellenes endured sundry exotic experiences, actual and terrifying, along the way. But they took poetic license with their encounters with fate across the waves.

The first travelers told their stories to others, who added their own embellishments, who passed them down to further generations still, ad infinitum. Tongue to Ear.

“Like a game of telephone,” my son aptly put it, when asked if he understood the concept of myth and oral tradition.

The egg, which Virgil laid inside the Castel dell’Ovo, is fragile. Andrea expounded, in this ring of fire and tremors. It’s also a symbol of life, “the fer-til-ity.”

The myths, they are not true, exactly. And the Greeks, they knew this. But they tell us something true, about Napoli character. About ourselves. The forces surrounding us, the wind and mountains, the sea—you know?

Sí, Andrea.

The myth of the isle of Megaride and seaside Naples is that it sits on the back of “a huge mermaid,” as Andrea slowly introduced the concept for my son’s sake, step by step.

“Actually,” he wagged his finger, “not a mermaid, more like a Siren—you know this word?”

I reminded Arr-ison of Odysseus, stuffing his ears with wax and binding himself to the mast to avert their irresistible spell, the beautiful songs. The locals call Sirens the Partenopei. The name of Napoli’s seafront, and their football team. Roma are Il Lupi—the wolves. After their own founding legend, of Romulus and Remus’ suckling she-wolf.

“You see this rock?” the guide caressed a brick in the guard-tower wall.

Tufa. Compressed volcanic ash. Soft and stable, easily carved, yet resistant to seismic shock. “All of Napoli is built of volcanoes.” The Phlegraean Fields of Fire, where we’re headed.

To Cuma.

To consult an Oracle. Predict the future, and touch fingers with the past.

“I take you.”