With Halloween around the corner, it’s as good a time as any to introduce a cartoonish subculture with surprisingly complex roots… and smuggle-in a brief history of the English language as well.

I live in Portland, where some citizens leave their decorations up year round, and others sport leather trench coats with Doc Martens in June—so publishing this a month before Halloween doesn’t feel inappropriate.

Most people associate the word “Goth” with teenage fashion choices like the ones parodied above, from Southpark’s “Dawn of the Posers.” This thespian, if you can believe it, was bullied for similar sartorial choices in high school.

If you’re familiar with Roman history, you recall the Goths were a group of Germanic tribes, one of which invaded Rome, leading to the downfall of the western empire in 476 AD. But how did we get from the dawn of the Dark Ages to Dawn of the Dead (or for that matter, “Dawn of the Posers”)?

The missing link between these seemingly disparate identities is a Romantic literary genre from the nineteenth century, Gothic horror—Dr. Frankenstein pointing the way to Dr. Martens. But let’s start with the youth fashion trend, which has its roots in a musical subculture.

The first recorded use of the word Gothic, as applied to pop fashion and music, occurred in the milieu of Mad Men (see Christina Hendricks above). A music critic named John Stickney coined the term gothic rock after meeting Jim Morrison, in 1967:

The Doors met New York […] at a press conference in the gloomy vaulted wine cellar of the Delmonico hotel, the perfect room to honor the Gothic rock of the Doors.

On the same tour the Doors were introduced to Andy Warhol’s Velvet Underground, whose 1967 release “All Tomorrow’s Parties” was later described as a "mesmerizing gothic-rock masterpiece," by Kurt Loder in 1984. The Doors-Velvets encounter has since been mythologized by Hollywood.

It’s not insignificant that these two prototypes of “Gothic rock” met in New York City, for more reasons than one.

New York, after all, is “Gotham City.” A moniker forever tied to Bill Finger’s Batman issue no. 4 (more on bats, and Batcaves, in a moment). Finger’s nickname for Manhattan actually goes back much further than a 1940 issue of Batman, to Washington Irving in 1807. The author of “Rip Van Winkle,” and the American Gothic classic “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow” (now synonymous with Halloween thanks to Walt Disney, on par with Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Raven”), called New York “the thrice renowned and delectable city of GOTHAM,” in a collection of essays. (Irving also coined the term “Knickerbocker”—as in the NY Knicks—in A History of New York, From the Beginning of the World to the End of the Dutch Dynasty ... by Diedrich Knickerbocker). Strictly speaking, the place-name “Gotham” comes from another tribe of Germanic barbarians separate from the Goths, the Anglo-Saxons—but that’s close enough, for now.

Gotham City was also the birthplace of a certain musical subculture from the lower East Side, named by “resident punk” Legs McNeil, after he started a fanzine with cartoonist John Holstrom and publisher Ged Dunn in 1975, Punk magazine. McNeil’s Please Kill Me: the Uncensored Oral History of Punk made the genealogy explicit between Jim Morrison and the Doors, Nico and the Velvet Underground, Iggy Pop and the Stooges, and what would later become known as punk rock, when he traced the lineage of these musical styles in 1996. The common denominator was often this man, Danny Fields, who managed all three.

Or you might say the common denominator was this towering German femme fatale, who slept and/or performed with members of all three.

If you combine the accoutrements of Nico, Jim Morrison, the Velvet Underground’s Lou Reed…

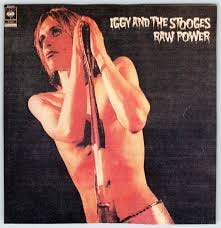

with Iggy Pop…

You’re halfway to “goth” without even traversing “punk.” If you add Richard Hell (a gothic name if there ever was one) - the man credited with turning ripped T-shirts and safety pins into fashion accessories…

Add some David Bowie from 1974’s Diamond Dogs tour,

Or campy vampire Bowie from Hollywood in 1983…

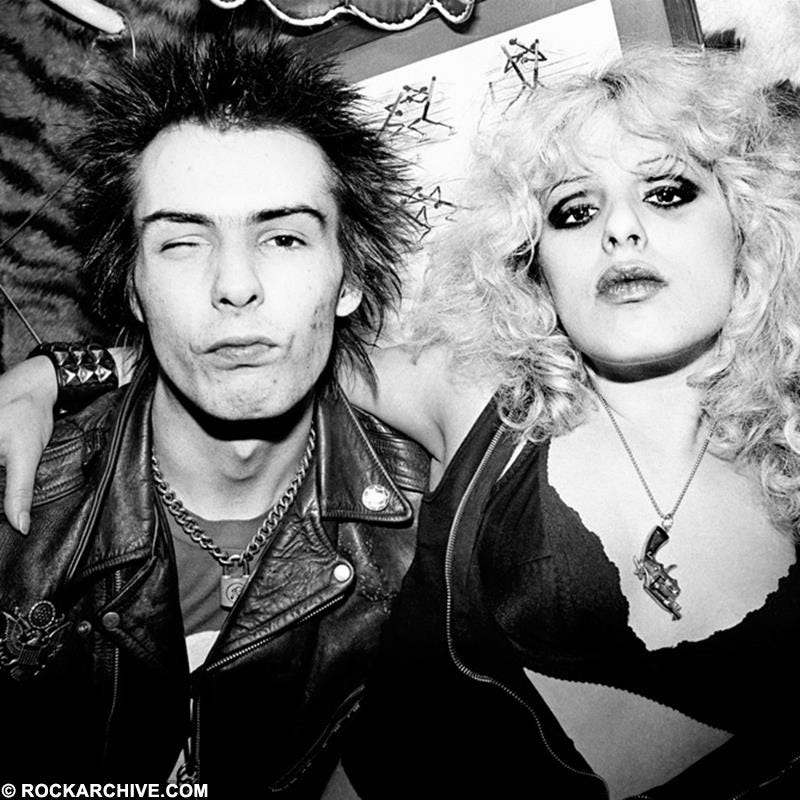

Throw in some Sex Pistols, and the more outrageous elements of punk fashion once the music crossed the pond, exploding as a popular class movement in the United Kingdom…

Paint it black, and punk starts to look like the first generation of goth rockers in Southern England, known as “Batcavers.”

The Batcave was a weekly club-night in London’s Soho district, originally hosted at the Gargoyle club, that began in 1982. It attracted the likes of Nick Cave, Siouxsie and the Banshees, the Cure, and Bauhaus. Siouxsie Sioux of the Banshees and Robert Smith of the Cure (who to this day looks like a cross between Edward Scissorhands and the Joker), are often cited as progenitors of goth fashion.

Jonny Melton of the Specimens described the early gothic rock scene at London’s Batcave:

It was a light bulb for all the freaks and people like myself who were from the sticks and wanted a bit more from life. Freaks, weirdos, sexual deviants ... There's people around who'll always be attracted by something shiny, glittering, exciting. At the time the Batcave wasn't a doomy, Gothy, droney grungey sort of place ... It was more Gotham City than Aleister Crowley.

Other bands in the UK’s post-punk, glam rock, and new wave orbit, such as Joy Division, were repeatedly characterized as “gothic” around this time. But the starting point of this musical sub-genre is generally attributed to Bauhaus’ first single released in 1979, “Bela Lugosi’s Dead”—named after Hungarian-American horror film star Bela Lugosi, whose most famous roles include Dracula (1931), and Ygor Frankenstein in Son of Frankenstein (1939).

That brings us back to the nineteenth century, to the Gothic horror of John William Polidori’s The Vampyre (1819), inspired by Lord Byron one stormy night in Switzerland, conceived in the same story-telling contest that begat Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (1818). If you lived through the end of the last century or the beginning of this one, you probably know the chronology of the story in the other direction.

B horror films, bat-shaped earrings, coffin necklaces, black lipstick, Marilyn Manson, Columbine, disaffected teenagers… that one kid from The Sopranos—a nebulous subculture that became a safe-haven for self-harmers and the neuro-divergent, or anyone else wishing to Live-Action-Role-Play outsiderdom, including Mad Men’s Christina Hendricks. An affectation ripe for “Dawn of the Posers” parody.

It’s easy enough to trace the connection between Gothic horror and goth subculture, from Edgar Allan Poe to the kid above—but what made nineteenth-century Romantic literature “Gothic” in the first place? What do melancholic English writers have to do with the marauding Germans who conquered Rome?

That requires a partial history of the English language. (If you desire a more comprehensive overview, I recommend The History of English podcast, which includes a gloss on Bauhaus’ “Bela Lugosi’s Dead.”)

Most English speakers are aware that their native tongue is considered a Germanic language (whatever that means). Perhaps they’ve heard it contrasted with the Romance languages of Italy, France, Portugal and Spain, derived from Latin. But fewer English speakers are aware that both Romantic and Germanic languages derive from the same linguistic family, one they share with Slavic, Sanskrit, Hindi, Urdu, and Persian tongues (to name just a few), called the PIE or proto-Indo-European family.

Millenia ago, before the end of the last major ice age, PIE speakers dwelt on the Eurasian steppes north of the Black and Caspian Seas. As the glaciers receded (perhaps causing the Great Flood that is universal in the comparative mythology of these people’s descendants), PIE speakers, who led a nomadic pastoral lifestyle (making them some of the earliest Homo sapiens to develop a tolerance for the animal milk that sustained them), branched out from the steppes.

Steered by geological barriers like the Caucasus mountains, following game migrations and seeking pasture for their animals, some wandered southeast into Asia Minor and the Indian subcontinent, spawning the Indo-Iranian languages. (Modern Persian, or Farsi, is surprisingly easy for English speakers to pick up—except for the fact that the Persian tongue was combined with the Arabic alphabet, making it difficult for Europeans to read and write). Some PIE speakers migrated southwest, into the Balkan peninsula, where their language morphed into archaic varieties of Greek. Others migrated further west, into the region of the Italian peninsula, to speak the Italic languages that would evolve into Latin, and after the fall of the Roman empire, the Romance languages. A broad swathe extending across central Europe north of the Italic regions as far as the British isles belonged to the Celtic language family, which included the language of the Gauls in modern France, Gallic (or Gaulish)—until the Gauls were subdued by Julius Caesar, and Latinized. North of the Rhine PIE evolved into the Germanic languages, which included Old Norse and German, the language of the Angles on the Jutland peninsula (modern Denmark, the hooked shape of which gave a name to the Angles, the country of England, and fishing, or “angling”), and the language of the Saxons. When the Angles and Saxons invaded Britain, Britain became “Angle-land,” and proto-English became an Anglo-Saxon or “Germanic language” (this is a bit reductive, however, as I’ll address in a minute). Another sub-variety of the Germanic languages that developed in southern Scandinavia and eventually migrated south (like Norse-speakers, in the following centuries), was the language of the Goths.

As Gothic speakers migrated south, they splintered into further sub-varieties—the Visigoths, who eventually settled on the Iberian peninsula (where they mixed with Latin speakers as part of Roman Spain), and the Ostrogoths northeast of the Italian peninsula, many of whom became part of Roman society as well. The Ostrogoths starving on the borders of the Roman empire, however, pressured by the invasion of the Huns farther to their east, were the “Goths” who were eventually compelled to invade Rome in the fourth and fifth centuries AD, mostly out of desperation.

Around the same time, the Germanic Anglo-Saxons invaded and settled much of Britain, with the exception of a few Celtic holdouts like the Picts and Scotts, and parts of Ireland and Wales, which remained predominantly Celtic or Gallic. The only reason these regions spoke Celtic languages instead of Latin in the fifth century was because these were the regions north of Hadrian’s wall, or beyond the reach of Roman Britain, which was originally Celtic-speaking, and then Latinized, again by the conquests of Julius Caesar (and later, Emperor Claudius).

In the ninth century, Germanic Norse speakers began invading Ireland, England, and the coast of modern France. When these “north-men,” or Norsemen from Norway—the Vikings— conquered the northwest coast of France, they gave their name to a region, Normandy. As a former part of the Roman empire (Gaul), the region they conquered was heavily influenced by Latin. In 1066, William the Conqueror, a Norman duke, invaded England during the Norman Conquest, and infused Anglo-Saxon England with a flood of Latinate words from France—one of the reasons English has such a plethoric vocabulary: it retains words of both German and Latin origin, the latter of which were added to the English language by (confusingly) a man descended from Germanic conquerors, or Vikings—William the Conqueror. In addition, as a former Roman colony, half of Britain had already been exposed to Latin words a millennium earlier. Thus, English is a “Germanic language,” but sixty percent of our words come from Latin.

So what?

All of this linguistic science is a product of English and German scholars from the late-eighteenth and early-nineteenth century—the exact time period and literary culture that birthed Romanticism and Gothic literature in these two countries. In 1786, during the first wave of Romantics (Wordsworth and Coleridge) William Jones, a British philologist living in Bengal, noticed the similarities between Sanskrit and English, and caused a sensation when he hypothesized the common origin of Sanskrit, Greek, Latin, Persian, Celtic and Gothic languages. In 1822, during the second wave of English Romantics (Byron, the Shelleys, Keats, and the man who introduced The Vampyre to English literature, Polidori), German philologist Jacob Grimm (of Grimm’s fairytales), established Grimm’s Law, systematically demonstrating sound changes across the PIE linguistic groups that were too consistent to be mere coincidence, all but proving their common origin. By the Victorian era, when Bram Stoker’s Dracula was published, Indo-Europeanists had refined Jones’ and Grimm’s observations into a science of linguistics.

The legacy of these incredible discoveries is fraught. Like the Romantic movement which it influenced, nineteenth-century linguistics was fodder for nationalism—the German fairy tales catalogued by Jacob Grimm were regarded as quintessential northern European culture, over and against the classical influences of Greece and Rome. Hitler derived his theories of racial purity from specious interpretations of scholarship similar to the work of Jacob Grimm—the Aryans, ironically, were a PIE linguistic group from the Indian subcontinent. The Germans were derided by the Allies as “Huns” after Kaiser Wilhelm made a stupid comment likening his German troops to the Asiatic conquerors who pressured the Goths into a desperate situation, the Huns, forcing the Gothic invasion of Rome—also based on an abuse of this history.

The Romantics were fed up with classical eighteenth-century Enlightenment ideals and the Industrial Revolution, and turned to medieval lore and the natural landscape of their native countries for inspiration, which tracked with Grimm’s fairytales and local folk traditions, particularly Germanic ones. Because “the Goths” were the antithesis of Rome, any product of culture—particularly Gothic architecture—not derived from classical influences was derided by Italians, and eventually embraced by northern Romantics, as “Gothic." The setting of so many works of Gothic romance and horror were Gothic architecture and spooky natural surroundings—ruinous castles and gargoyled cathedrals, moonless moors, midnight roads, or dark forests recalling the Middle Ages. It is this sense of the macabre, the terrifying, the supernatural, the grotesque—blood and bats, vampires and Frankenstein monsters, etc—that would come to define “Gothic rock” in the twentieth century. The Victorian era, heavily influenced by Romantic tropes, was equally influential on the sartorial affectations of goth subculture.

Outside of England and Germany, in America, one of our earliest novels, Weiland, or the Tranformation (1798), is regarded as the first work of “American Gothic” fiction, with a distinctly German title. The author, Charles Brockden Brown, kicked off a genre that would come to include “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow” (1820), and Poe’s “The Raven” (1845).

The connections between the postmodern goth and ancient or medieval Gothic are best understood as a constellation of recurring symbols with shifting meanings, as opposed to a strable trajectory from the Ostrogoths to Southpark’s “goth kids.” Yet the persistence of these symbols is often remarkable. Nico was characterized as a German amazon invading America. Jim Morrison was obsessed with the philosophy of Friedrich Nietzsche, an existentialist staple of punk and goth, malappropriated by the Nazis before that. Bauhaus (the band) was named after the German school of design, which became a movement after it was forced to relocate to the U.S. during World War II (Bauhaus means “building house” in German, almost invoking Gothic architecture when paired with Dracula and Bela Lugosi). The punks, whose influence on goth culture is so direct, were infamous for ironically incorporating Nazi symbolism for shock value, as evidenced by the Dead Boys, Ron Ashton of the Stooges, and so many others. Joy Division, another “gothic” band, was ironically named after a Nazi army division dedicated to… sexual reproduction of the Aryan race. (Remarkably, from a 2023 perspective, these cancelation-worthy faux pas, like the minstrel lyrics of certain Rolling Stone songs, go mostly unmentioned.) The Banshees were named after figures from Celtic, as opposed to German, mythology—but in a culture derived from Romantic influences where “Gothic” simply meant “not Greco-Roman,” we might put screaming banshees in the Gothic category as well.

Goth style has been likened to bricolage—the opportunistic use of mixed media and found materials to cobble an expression together in a work art. In a subculture, like punk, defined as nihilistic and “anti-” everything (Richard Hell and the Voidoids’ “Blank Generation”), the antagonists of Roman civilization are a fitting emblem. As I’ve argued elsewhere, rock and roll is essentially a form of primitivism, which is always a critique of one’s own civilization in favor of one that is supposedly less-civilized. As Tacitus argued in Germanicus after confronting these tribes: Yes, “the Goths” were primitive barbarians—but, he sometimes suggested, weren’t these imbeciles in some ways morally superior to the decadence of Rome?

Perhaps… up to a point.

Happy early Halloween from Portland, where it’s always Halloween. If the goth kids come to invade your doorstep next month, give them Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Tell-Tale Heart,” narrated by Iggy Pop (illustrated by Ralph Steadman).

It’s better than candy.