It’s funny the way most people love the dead. Once you are dead, you are made for life.

— Jimi Hendrix

Since the cult of Orpheus, music’s been linked with memory and the prospect of raising the dead. Since the songs of Homer, words and rhythm have served as mnemonic devices for the resurrection of heroes past. Now, as pieces of old music are combined with artificial intelligence, that power has been increased, perhaps cheapened, exponentially. The Beatles recently released the “last Beatles song,” decades after the demise of half the Fab Four, thanks to machine learning. As Mick Jagger recently told the Wall Street Journal, "You can have a posthumous business now, can’t you? You can have a posthumous tour. The technology has really moved on…”

That only works if something resembling the original music remains part of the equation, however.

For years, as a parade of increasingly successful pop-music “biopics” proceeded—from Your Cheatin’ Heart (1964) to The Buddy Holly Story (1978), La Bamba (1987), Great Balls of Fire (1989), The Doors (1991), Ray (2004), and Walk the Line (2005)—I awaited the day when the myth of Jimi Hendrix might be immortalized by Hollywood. In 2013, Jimi: All Is by My Side, directed by John Ridley (12 Years a Slave), starring Outkast’s André Benjamin in the titular role, was released.

An utter disappointment, despite the talent involved. Not because of failed acting or directing, or the fact that one of the more appalling scenes depicting domestic violence was denied by the alleged victim herself, Hendrix’s girlfriend Kathy Etchingham.

Jimi Hendrix’s music wasn’t part of the film.

No overdubs of classic songs, which might’ve been quite interesting, performed as they would’ve been by Atlanta rap genius André 3000. Instead, the film score leaned on milquetoast Hendrix-esque guitar noodlings, performed by studio musicians. This appears to be an issue with a number of Hendrix documentaries, too, and it has to do with licensing.

The executor of the Hendrix estate, who was nine years old when she became his adopted step-sister, often refuses the right to Hendrix’s music in films. Perhaps, in the case of the biopic, because of unflattering (and apparently untrue) depictions of the star engaged in domestic violence. Perhaps because Janie Hendrix herself wasn’t involved in the making of the biopic. Or perhaps she simply smelled a flop, and ensured it would become one without Jimi Hendrix’s music.

The history of Hendrix litigation is beyond byzantine, but one thing hasn’t changed since the guitarist’s death in 1970. Because he failed to secure a will, was notoriously careless about signing contracts, and created hundreds of hours of unreleased material before his death, a string of lawyers, promoters, and family members have tried to assume control of that unreleased material for over half a century, with Janie Hendrix succeeding in the end.

I won’t pretend to offer a balanced verdict any time soon; this is the beginning of a long, convoluted investigation that (maybe someday) culminates with a petition to settle this dispute in a manner that allows the Hendrix catalogue to be licensed respectfully. At least once—in a meaningful biopic about James Marshall “Jimi” Hendrix, featuring his own music. (If that sounds like a pipe dream—and perhaps it is—I know of others who’ve employed similar tactics, on this platform.)

The first journalist to dig beyond the surface of the Hendrix litigation was Jerry Hopkins, co-author of a book that cemented Jim Morrison’s legacy (although rather speciously) in 1980, No One Here Gets Out Alive (he also wrote a biography of Jimi Hendrix, before he passed away in 2018).

In 1976, Hopkins published a lengthy article in Rolling Stone, “A Piece of Jimi Hendrix’s Rainbow: How a calculating band of lawyers, promoters, cons and other vultures have plundered the grave of Jimi Hendrix.” At the time, the players attempting to profit from the Hendrix estate consisted of the guitarist’s managers and attorneys, and a pair of shady promoters selling everything from candy bars to rubber stamps emblazoned with Hendrix’s image, at a time when his posthumous worth was supposedly around $20,000 (due to errant book keeping, possible mob ties, money laundering, and embezzlement). The original figure quickly ballooned into the millions.

For enthusiasts, Hopkins’ article is worth the long read, though it’s easy to become overwhelmed by the sheer variety of parasites named in the first chapter of this sordid tale.

The gist is this: Hopkin’s account ends with Al Hendrix, Jimi’s father, nominally assuming some form of control over his son’s estate in 1976—though it sounds more like a yearly allowance in the form of lifetime annuity, set up by his lawyer. This allowed the elder Hendrix to continue working as a self-employed gardener, leisurely servicing a handful of clients, providing him a modest residential estate, where he could sip beers from his basement wet bar as he transitioned into semi-retirement, where he was interviewed by Jerry Hopkins:

“Doesn’t matter,” Mr. Hendrix added. “It’s just money that come to me. I still have my gardening.”

One gets a sense of where his son’s disregard for financial arrangements originated.

The lawyer who brokered this arrangement for Al Hendrix was alerted to the case by Jimi Hendrix’s valet, who had previously worked for Nat “King” Cole, and was appalled at the prospect of his former employer’s estate being valued at a mere $21,000 at the time of his death in London. When he escorted Hendrix’s body from London to Seattle, the valet brought the case to an attorney named Leo Branton, known for representing celebrities, including Nat Cole, and working pro bono to defend 13 members of the Black Panther party, as well as Angela Davis.

While the elder Hendrix was happy enough with his allowance, Branton and his associates took advantage as the de facto executors of the Hendrix estate, “raking the money in,” in Al Hendrix’s words, through a recording facility Jimi had designed with his manager, Electric Lady Studio. Al Hendrix expressed no interest in the enterprise, initially: “Well, hell, I don’t need no studio . . . Everybody likes to get his finger in the pie . . . Leo [Branton, Angela Davis’ lawyer], he told me I was well fixed for life.”

In 1974, Branton convinced Al Hendrix to transfer his son’s catalogue to a Panamanian corporation, started by Nat King Cole, Presentaciones Musicales, which served as a tax haven. The rights were subsequently transferred to two Bahamian tax shelters, until Branton sold the Hendrix catalogue to MCA in 1993, which finally caught Al Hendrix’s attention. He was still under the impression the rights belonged to him.

Paul Allen, late founder of Microsoft—a Hendrix fan who, according to Quincy Jones, could play the guitar almost like his idol (perhaps he should’ve been enlisted for the biopic soundtrack)—offered his financial assistance to the Hendrix family in reacquiring the rights to Jimi Hendrix’s music. With the threat of a financial juggernaut backing Al Hendrix, Branton opted to settle out of court for an undisclosed sum. Al Hendrix officially assumed control of his son’s recorded output, unreleased material, photos, film, and the right to exploit his image, a catalogue valued at $80 million in 1994.

This arrangement continued until his Al’s death in 2002, when a legal battle between Jimi’s half-brother Leon and his adoptive stepsister Janie Hendrix emerged. There were a few entanglements with the former members of the Jimi Hendrix Experience, Noel Redding and Mitch Mitchell, in the early nineties as well (the most recent lawsuits, in 2022-23, involved the heirs of Redding and Mitchell, contesting Janie Hendrix’s Experience Hendrix, LLC and Sony Music)—but the most contentious battle, the one that I suspect explains the subpar soundtrack on Hendrix’s biopic, has been between Jimi Hendrix’s half-brother and his adoptive stepsister, Janie.

It’s a family feud, and a sad state of affairs. Clearly, Al Hendrix intended his stepdaughter to become the rightful heir to the Hendrix estate. But what would Jimi Hendrix think of his only surviving, legal blood relative receiving a single gold record as his inheritance?

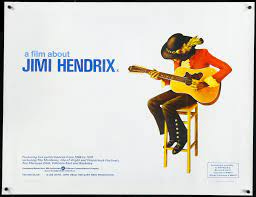

Over the years, I’ve watched my share of Hendrix-related documentaries, and nothing is ever quite as it seems. Perhaps the most candid—and moving, because it features actual live performances by Hendrix himself, in addition to testimonials from contemporaries like Mick Jagger, Lou Reed, and Little Richard—is 1973’s Jimi Hendrix.

Even in 1973’s Jimi Hendrix, Al Hendrix comes across as a soft-spoken, sweet old man who raised two sons by himself—the elder Jimi from the age of ten—following his mother’s death. In Jerry Hopkin’s article, he likewise appears as a laidback, non-litigious heir who just wants enough money to supplement his small gardening business and beer drinking habit.

In other documentaries, according to Jimi’s younger brother Leon, his father consoled two young sons after their mom’s death with a tall glass of 7-and-7, and little else. He also put up his other children for adoption. Later, he married a Japanese woman with a daughter named Janie, adopted her as his own, and eventually transferred Jimi Hendrix’s estate to her.

It’s tempting to dismiss Jimi’s estranged brother Leon as a troubled pretender to the family fortune, given their difficult relationship, Leon’s struggles with substance abuse, a stint behind bars—and his association with this man. “Cannabis consultant, Mentor,” and “Radio Talk Show Host,” Andrew Pitsicalis.

Pitsicalis is a serial infringer who’s been sued more than once by Janie Hendrix and the Experience Hendrix LLC, along with his business partner Leon, for attempting to “hijack trademarks and copyrights for their own personal gain," according to one court filing. As the operators of HendrixLicensing.com and Purple Haze, LLC, Pitsicalis and Leon Hendrix have hawked a variety of products featuring Jimi Hendrix’s likeness, including cannabis, food, alcohol, and ‘medicine,’ as well as “T-shirts, posters, lights, dart boards, key chains and other items designed to capitalize on the fame of the rock legend,” according to the Hollywood Reporter. Purple Haze Properties represents: “the greatest guitarist in Rock 'n' Roll history, 'my man,' Jimi Hendrix"—according to Pitsicalis.

According to Leon: "I know my brother would have been a huge fan of the things that we have been doing with Purple Haze Properties. His creative spirit lives on in everything we do."

(Ahem.)

In 2014, the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals awarded “a victory to famous dead people,” per the Hollywood Reporter, when it reversed a 2011 ruling that found that the state of Washington’s generous likeness statutes, which give greater control over the use of postmortem images than many other states, were unconstitutional. The 2014 reversal granted control over the use of Jimi Hendrix’s image to the official Hendrix estate, at least in states like Washington, where Janie Hendrix resided and Jimi Hendrix was born. There, “the heirs of famous people can sue . . . to protect names, likenesses, voices, mannerisms, images, gestures, signatures and more”—to their own benefit. And to the detriment of jilted would-be heirs like Leon Hendrix.

As the legally-adopted heir to the Hendrix estate, Janie Hendrix has the imprimatur of Hendrix’s respected sound engineer, Eddie Kramer. She speaks on behalf of Jimi Hendrix often, weighing in on his death and other matters, and enjoys the benefit of mainstream press coverage.

However, many of her recollections of Jimi Hendrix, from when she was in elementary school, sound roseate. According to Janie, Jimi “would call home all the time,” and “have these family forum discussions where we would all sit in a circle in the living room,” playing Monopoly late into the night.

Jimi Hendrix visited his hometown of Seattle for the first time since 1961 in 1968. According to contemporary reports, it was an awkward homecoming—he did play a show, and drunken Monopoly at home, then appeared at his old high school hungover, shy and barely able to speak. As he left he told the assembly at Garfield High, “Right now, I’m going to say goodbye to you, and go out the door, and get into my limousine, and go to the airport. And when I get out the door, the assembly will be over.”

Two years later, he was dead.

Though Hendrix had a rocky relationship with his half-brother, he recorded two songs about Leon towards the end of his life, expressing regret for having to turn his brother away, and deny his requests for money: 1969’s “Shame, Shame, Shame” and “It’s Too Bad.” After a Washington state judge reduced Leon’s share of his brother’s inheritance, in 2002, to a single gold record his father had given him, Janie Hendrix had this to say:

"Jimi wrote a song about Leon and it was called, 'It's Too Bad'. The lyrics to that song are what this is all about."

That may to be the case. The song also laments Leon’s disdain for his brother not being “black” enough.

Jimi Hendrix’s songs, under his stepsister’s aegis, have been licensed in numerous films and commercials. The right to the posthumous manipulation of his image and music—the right to raise the dead—resides with her. Previously unreleased and repackaged Hendrix recordings appear almost annually.

But one has to wonder: why so little in films about Jimi Hendrix himself? Especially a Hollywood biopic, starring a musical genius, from an Academy Award-winning director?