Last week, a favorite historian published a tribute to his late friend and fellow critic, Scott Timberg.

Since I’ve mentioned him several times already, I’ll stop referring to this “favorite music historian of mine” by euphemism and just go ahead and tell you his name—Ted Gioia. (If you know me, you’re probably familiar with his name, or pieces of his work already).

Ted’s an interesting guy, who doesn’t really fit any preconceptions about what a music critic should look like—a jazz pianist (that part makes sense)—who subsequently spent years consulting for Fortune 500 companies and Silicon Valley. (In this he’s not alone—here’s another musician, the future VP of Sony tech standards, a formatter of the Blu-ray disk, on stage with the Stooges in 1974…)

Ted grew up in South-Central L.A. and graduated in Palo Alto and Oxford, with an MBA… and a philosophy degree. After school he went from gigging around the Bay Area to leveraging buyout offers, only to become a professional historian with eleven books in print, now turned Substack proselytizer. He’s a literary critic as apt to make market predictions about the streaming industry (he’s something of an oracle in that department) as he is to tell you the history of a medieval troubadour ballad. In some ways a conservative guy—never touched drugs—who writes about shamanism and mystical experience (refreshingly, without any of the New Age hokum). Like an abstinent version of Jimi Hendrix or John Coltrane—music is his drug. Someone who had dinner with Saul Bellow one night and breakfast with John Cheever the next morning when he was a kid at Stanford, and worked with sax icon Stan Getz along the way.

I’ll write more about Ted Gioia later, he deserves his own edition. For now, I’d like to focus on the colleague he was paying tribute to, Scott Timberg.

I only discovered Ted Gioia, and by extension Substack, through the work of Scott Timberg. By the time Substack rolled around, Timberg was no longer with us.

It’s a tragedy, because he would have thrived here. In fact, he would have been Ted Gioia’s partner at “The Honest Broker”—a unique newsletter for arts and culture with an incredible readership, spangled with some genuinely-famous music-and-lit personalities—composers, novelists, etc.

Unfortunately, Timberg succumbed to the plight of the publishing industry instead. As a composer, and someone who wrote about music, I suspect the decline of the music industry didn’t help. As I mentioned in a previous post, like many journalists during the rise of digital media, Scott Timberg was laid off from a newspaper.

After several years as a freelance creative struggling to make a living in this environment, he took his own life. In the back of my mind, I always assumed he must’ve been suffering from addiction or a depressive artistic temperament, like the ones he often wrote about in his work. It turns out he was just a homeless wanderer in the desert of arts and publishing. A writer who no longer had a venue for his craft.

As Timberg describes in his articles, there are certain kinds of historically-specific, complex civic environments necessary for the arts to flourish in a socially-meaningful way. Historically they differ, but these environments all constitute a support system between creators and audience, patrons, and society as a whole.

I’m reminded of fifth-century Athens. Elizabethan England, Aachen under Charlemagne, Reims and Chartres during the cathedral era, the Islamic Golden Age in Baghdad, the Two Sicilies, renaissance Florence (which Silicon Valley loves to hopelessly compare itself to), or Mozart’s Vienna. New Orleans and Harlem in the early-twentieth century, Belle Époque Paris, or mid-fifties Memphis.

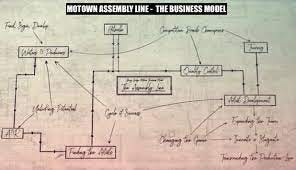

The civic environment documented in Hitsville: The Making of Motown, is another good example. In midcentury Detroit: strong public education, including music programs; “the most accessible orchestra on the planet,” the Detroit Symphony Orchestra, which staged free concerts attended by the future kings and queens of Soul; public works projects; and well-paying factory jobs in the auto industry at Chrysler, GM, and Ford, which inspired Berry Gordy’s business model at Motown Records—the hit factory, an assembly line for songs.

These factors are all related—an ecosystem. In smaller, less-analog ways, I’m hoping Substack, created and soon-to-be owned by writers, will provide a simulacrum of these support systems, for the art of letters. It’s modest, and digital—it’s not Detroit in 1959—but it’s something. It’s only a matter of time before someone extends this business model to music publishing—again. (Bandcamp succeeded admirably. Until they sold out to a $28 billion gaming company.)

I didn’t know it when I first encountered his work, but Ted Gioia’s late friend, Scott Timberg was a critic for the L.A. Times—by all accounts a phenomenal one. To hear Ted tell it, Scott was engaged in nothing less than a love affair with the city he wrote about. If you reside in the City of Angels, you may find it worth your time to dig up his old articles for posthumous insights into the city’s culture scene. Curious about a storied venue, museum, or any other L.A. institution… an artistic cohort of the past several decades? There’s a good chance Scott wrote something insightful about it.

Just last week, in fact, I stumbled across one of Timberg’s L.A. Times articles quite by accident—a book review of an anthology edited by Greil Marcus (the moderator and music critic I described in “Gathering Moss,” the first reviews editor at Rolling Stone).

The book was A New Literary History of America—which long ago became a source bible for the material in these columns. The reviewer happened to be the man who changed my conception of art and the people who create it… years ago, right around the time the world lost its collective copus mentis.

In 2016, I was in grad school. A little older than most of my cohort, a little younger than the rest. I was taking a course lectured by a mad Scotsman at Portland State University, a fish out of water at that institution, who turned me on to some crazy ideas I would rediscover later in the work of Ted Gioia.

Some of the ideas came from a Frenchman named René Girard, who happened to have been a professor at Stanford while Ted Gioia was a student (though he never took his courses). Other ideas were the brainchild of an Australian ethnologist named Michael Taussig, who unlike Ted Gioia, had definitely taken drugs—field work, don’t you know. The rest came from an American music critic named Scott Timberg.

I’m still applying the ideas of all three to the cultural history of America documented in Greil Marcus’ New Literary History. Much of this newsletter thrives on it.

At the time, as I mentioned elsewhere, there was an exciting new periodical circulating, in print and online, called Radio Silence.

The RS concept, plastered on the logo, was “Literature and Rock & Roll.” Two art forms, I was quickly learning—music and language—that have been intertwined since the beginning of humanity.

During the death of print, not willing to distract readers with pop-up ads online, the magazine was doomed to failure. The editor all-but knew this, but he made a last-ditch effort anyway. Do not go gently into that good night. Rage, rage, against the dying of the light, as Michelle Pfeiffer said. Or was it Rodney Dangerfield?

It was a labor of love, a Gift. It brought the people who worked on it, often for free, together. And it must’ve had the hippest audience since the salad days of the Paris Review or Rolling Stone.

Radio Silence received plaudits and/or literary contributions from the likes of Greil Marcus, Ted Gioia, a man best known by the pen name “Lemony Snicket,” and the various rock & roll musicians who wrote for the magazine—real articles and essays, no celebrity fluff—pieces about literature and rock & roll. The guitarist for the Submarines, writing about her great-grandparents, for example—Zelda and F. Scott Fitzgerald.

It was the organ for a community of musicians and writers who staged loft parties and music events around the Bay Area, as well as various contributors from around the country, who funded arts education in schools. Though it was based in Oakland, as the editor told me last week, its roots were in my hometown. Portland, where the founder, Dan Stone, had migrated from.

The article I remember most from Dan Stone’s passion project was called “The Origins of the Creative Class,” Parts 1-3, by Scott Timberg. It chronicled the history of the people who make and support art, and has become a part of my repertoire ever since.

Since I promised Ted Gioia I would do my small part to contribute to the memory of his friend; because his friend’s ideas are indispensable to the theory of art and culture I’m rolling out in the pages to come, this week is an opportune moment to introduce readers to “The Origins of the Creative Class: Part 2” by Scott Timberg.

Maintain Radio Silence. Stay tuned.