The Sybil is an Oracle. A fortune teller in Cuma, outside Naples, who speaks gibberish.

At least she did. It’s unclear whether she still hangs around, or not.

Why come here, chasing shadows? Who knows such things. I heard it in a story. Pieces I heard recently and others read long ago. Einstein’s words in a book my son is reading, three weeks after we left Cuma—the first paper book to engross him in moons… seem to have something to do with it.

The most wonderful thing we can experience is the sense of mystery. It is the source of all true art and all true science. Whosoever has never felt this emotion, who no longer knows how to stop and meditate and remain transfixed in fearful admiration, is like a dead man; his eyes are shut.

—Albert Einstein (epigraph to a book of Venetian Legends and Ghost Stories)

I wanted to touch fingers with the past. Where Greece touched Italy. To understand why so many have wandered here, and few any longer do. Actors, Romantics, novelists, screenwriters and directors, people playing themselves and others. Mythical wanderers from Greece and Troy, lost sailors looking for a way home.

I got myself a sort of one-man religion. I practice a faith long abandoned. Call it what you want. “Humanism” is one word, maybe. Fides quaerens intellectum, “the faith that seeketh understanding,” always out of reach.

And faith is neither the submission of reason, nor is it the acceptance, simply and absolutely upon testimony, of what reason cannot reach. Faith is: the being able to cleave to a power of goodness appealing to our higher and real self, not to our lower and apparent self.

—Matthew Arnold, "Literature & Dogma," 1873

That’s all I got to cling to. Appealing but not knowing, whether I’m coming or I’m going.

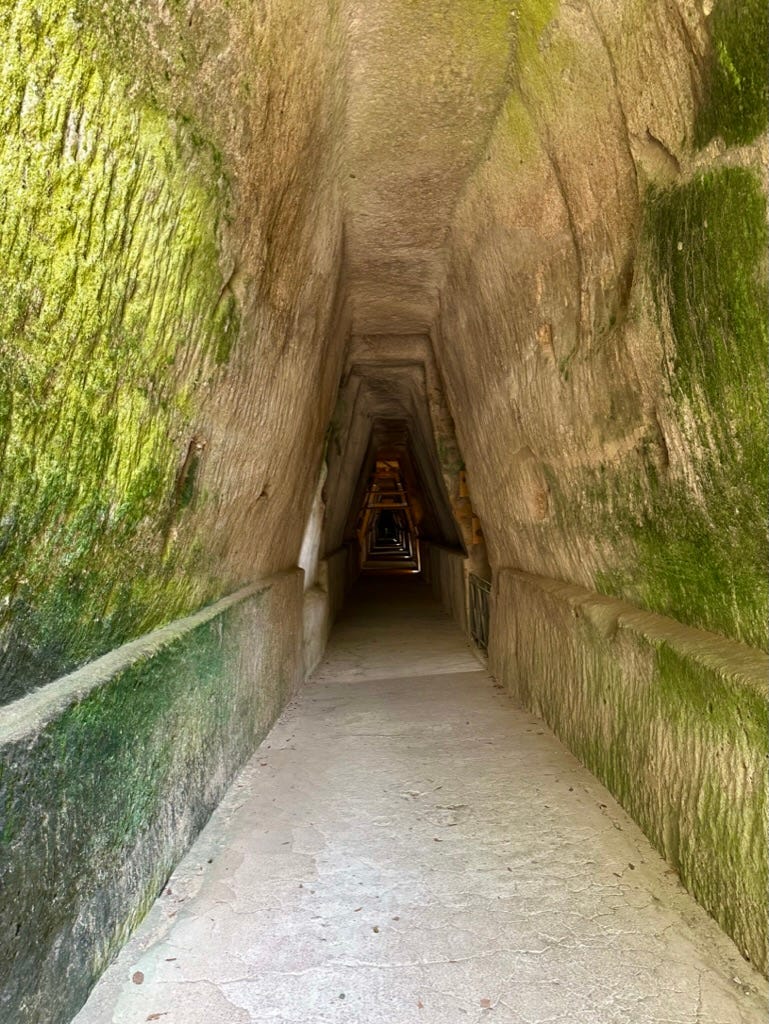

I came here on a pilgrimage—“from abroad.” To consult an Oracle who no longer exists. Visit a shadow called the Sybil. In an archeological site under the Temple of Apollo, in Cuma. To feel the Sun on the acropolis and listen for echoes of the soothe-sayer in her dark chambers below.

The two most important Oracles in the ancient world were at Delphi, in central Greece, and later, in Cuma. The first outpost of Greek culture on the Italian peninsula.

Both were home to cults of Apollo, Houses of the Sun. Priesthoods collectively known as “Oracles.”

Sisterhoods devoted to the god of truth and prophecy. Music, poetry and dance. Sickness and healing. Light and the Sun. Arrows. Deity of everything but disorder, Apollo.

The sole Olympian to shine under one name from Greece to Rome, Apollo.

From East to West. Many divinities or demigods specialized in various skillsets under Apollo’s aegis—music, healing, poetry, sunlight, truth, etc.

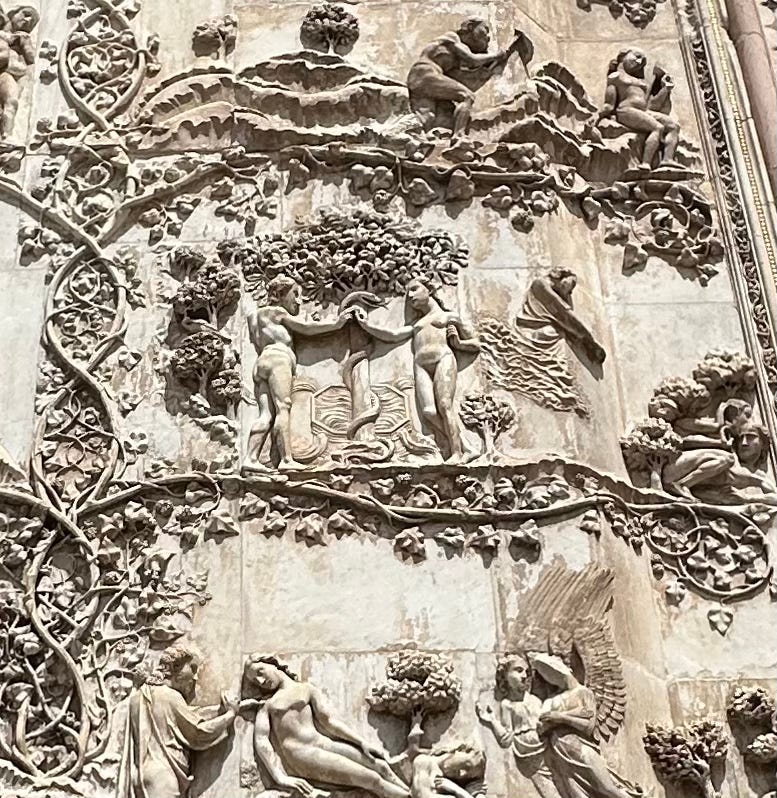

Many changed shape or names, from Egypt or Asia Minor to Greece. Mother goddesses, fertility figures torn to pieces, reassembled and resurrected. From Greece to Rome.

From Mt. Olympus to the Pantheon: Zeus became Jupiter. Hera-Juno. Aphrodite-Venus. Athena-Minerva. Artemis-Diana. Dionysus-Bacchus.

Apollo-Apollo.

The One Sun. Ra. Ripe for conversion to monotheism. Ready to absorb the old gods. But to every light there is a shadow.

Apollo’s prophet of note in Cuma, the Sybil who stands out in myth and literature, wasn’t exactly submissive to the Sun. And the prophecies of the Oracle sisterhood, the words of foresight uttered by the presiding Sybil in general, sound to me more like notes of chaos and disorder.

Music of another sort, beyond the confines of Apollo’s measured scale. The tones of Apollo’s philosophical and polar opposite, Dionysus.

Ecstatic gibberish spoken in tongues. Experimental music. Ancient pentecostal rock & roll, if you like. Freeform improv—the Sybil’s prognostic poetry.

If you ask me. Nietzsche maybe. Thomas Mann. James Douglas, Jim Osterberg, or Patti Smith.

The original Oracle, in Delphi, was centralized. Delphi was the omphalos, or “navel” of the world. Represented by this object. The bellybutton of Greece.

People from across the Mediterranean came to consult the priestess of Apollo in Delphi.

The Sybil of Cuma, unlike her centralized predecessor in Delphi, was extremely isolated. One of the reasons the Sybil seemed to speak in gibberish, my guide now friend Andrea theorized—other than being intentionally obscure, thus making her prophecies hard to disprove—was due to the fact that the priestesses in Cuma were so far removed from Greece, isolated and protected from the indigenous tribes by the surrounding mountains as well.

They may have developed their own dialect in Cuma, just as Latin would morph into the various romance dialects in isolation from the language of international trade and diplomacy, after the fall of Rome.

The Oracle of Delphi was said to derive her power of insight from inhaling the fumes of a decomposing serpent (“Python”), slain by Apollo. For this reason, the Sybil presiding over Delphi at any given time assumed the title “Pythias.” A trail of priestesses, in succession, under one name.

The snake whisperer.

Scholars and mystics alike have interpreted the fumes of Apollo’s “snake” beneath his temple in Delphi to be a form of Greek nitrous oxide—huffing geothermal gas. Inducing ecstatic visions, speaking in tongues, and foresight. However there’s less evidence of sacred gas in Delphi than in Cuma, today.

It’s more likely that in hyper-seismic southern Italy than in central Greece, the Sybil here in Cuma would’ve had access to intoxicating gas.

In the historical record, a “new mountain” arose next to Cuma in one day, and continued to grow for four more. So seismic is the area.

Flatland in the morning, hillside by evening, next to Cicero’s villa on Lake Avernus. This sort of abruption happens in south Italy; it happened in South America not so long ago, within living memory. People stand up next to a mountain, overnight.

Geothermal gas is beyond evident near Cuma. I breath it now, in the smell.

But la guida (Andrea, sacred guide of Naples) says “No.” Never heard that part of the story, the Sybil’s intoxicating gas. He has heard of other drugs—mushrooms, hallucinogens—

"Have you heard of Carlos Castaneda? You know Don Juan?”

Yes. And No. Don Juan was mostly a hallucination too, from what I understand. An imaginary medicine man dreamt up by a sixties shaman-conman, Castaneda, who had reason enough for desperate invention.

As for the Sybil’s jumpin’ jack flash—sometimes the locals don’t know their own legends. Or the legends attributed to them, which may or may not be hot air.

Whatever the source of their visions in Cuma and Delphi, the original Oracle of Delphi was in the middle of the action. The Delphic sybil heard news from far and wide, from people in high places. Which gave her an inkling of what was brewing geopolitically beyond the Aegean. From behind a ritualistic mask, which must have made quite an impression, she received the rumors and desires of her clientele, in their quest for enlightenment or self-interest—so Pythias had an advantage when it came to predicting, even affecting, outcomes with a straight face.

Insider trading, if you will.

In one account, according to Plato, the Delphic sybil flattered a famous philosopher. Informed a skeptical Socrates that he was the wisest man in Athens. Because of all Greeks, she told Socrates, the preacher of irony and dialogue, he was the only Greek to espouse: “I know nothing.”

In times like ours, or Socrates’; during the fall of Athens, Rome, or Europe. When a world is at its end:

The best lack all conviction, while the worst are full of passionate intensity.

Doubt is a virtue, and certainty a vice, as Yeats says here in so many words.

If the Hebraic serpent represents forbidden fruit, the consequences of Knowledge; the one rotting under Delphi poeticized doubt, in Plato’s account.

It’s one long snake, in my opinion. Tail in the East, head in the West. I see it everywhere I go. The same warning. From the ceiling of the Sistine chapel to the Pagan temples excavated under so many Catholic churches. To the echoes in my head: People tell me it’s a sin, to know and feel too much within…

The Sybil in Cuma was the Italian equivalent of Pythias in Delphi.

Like her Aegean counterpart, the Cumaean Sybil was the priestess presiding over “the Oracle,” a prophetic sorority dedicated to, and under the influence of, the god Apollo.

Another soothsayer-in-chief and fortune-teller, who told you what to think and what the future would bring, perhaps after the visionary huffing of geothermal fumes.

Originally Greek, the Sybil in Cuma was later adopted by the Romans, and became their preiminant prophetess, because of her proximity to the capital, and her role in Rome’s etiology (founding myth).

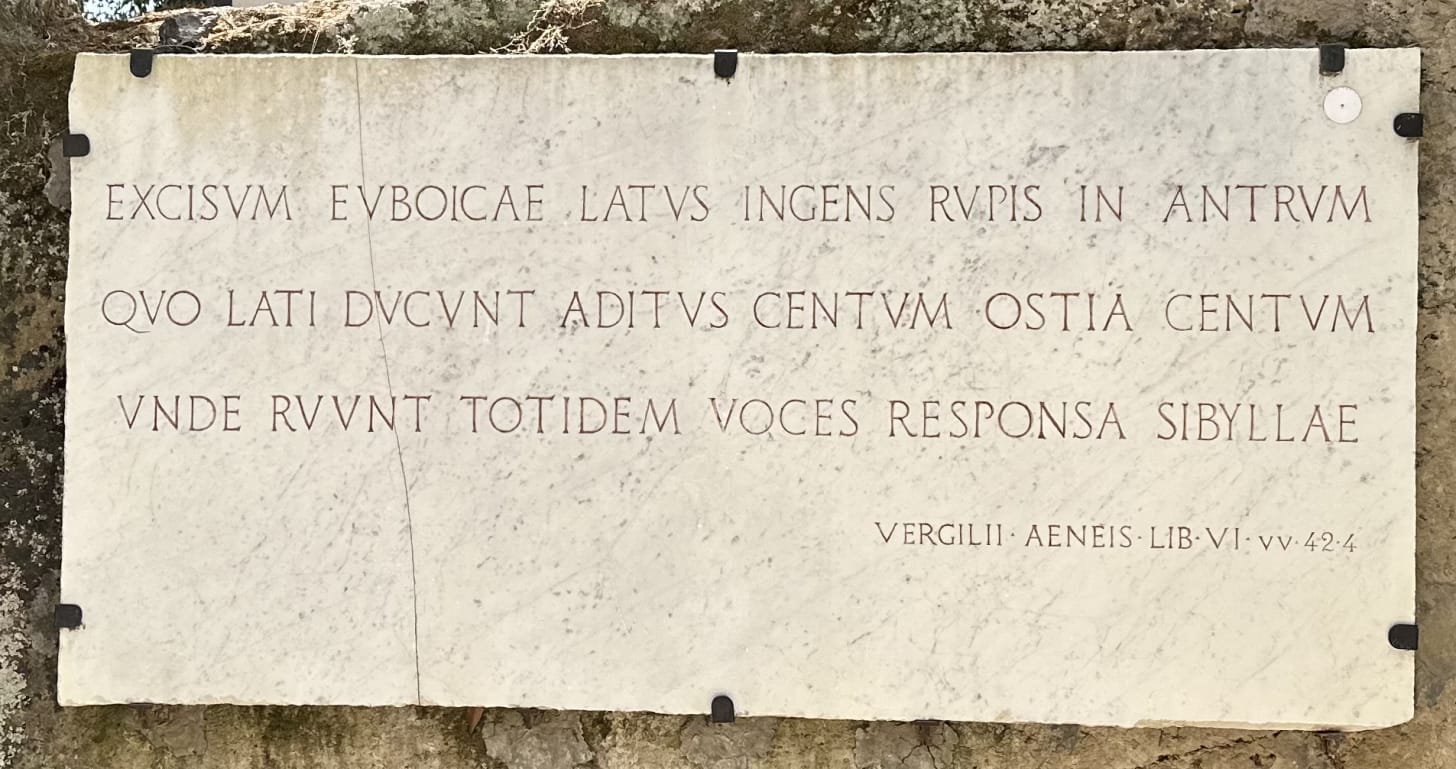

She appears in the epic poetry of Virgil’s Aeneid (29-19 BC).

In the mythological verse of Ovid’s Metamorphoses (8 AD).

In the bizarre verse-and-prose mixture of Petronius’ Satyricon (1st c. AD, an early antecedent of ‘the novel’)—the account of a slave-cum-aristocrat who takes decadence a little too far, once he’s an aristocrat.

And in David Chase’s The Sopranos, among sundry other texts.

The Aeneid is Virgil’s account of the defeated Trojan, Aeneas, and his wanderings after the fall of Troy, culminating with the hero’s establishment of Roman ancestry after his victory over local Italian tribes—Homer goes to Italy. Words and music by Virgil.

Through Aeneas, Virgil expressed a very real cultural link between Greece and Rome, part of which occurred here, when Greek colonists landed in Cuma. Colonists who brought with them not only Homer’s Odysseus, but ironically, the Greek’s defeated Trojan rival Aeneas—a wanderer in Italy, like themselves.

Part of a long and convoluted process of turning Troy into Greece, Trojan sojourners into Greek colonists, and vanquished Trojans into Roman victors. Long before Virgil, Greeks in Italy identified themselves with Aeneas.

Just as Virgil would identify Romans with Hellenized Trojans. After the fall of the Roman empire, much of Latin Europe would mythically identify itself with Greece-Troy-and-Rome, via their own founding myths, or “romance” epics (stories passed down in corrupted Latin, the romance languages of Italy, France, Spain, et al).

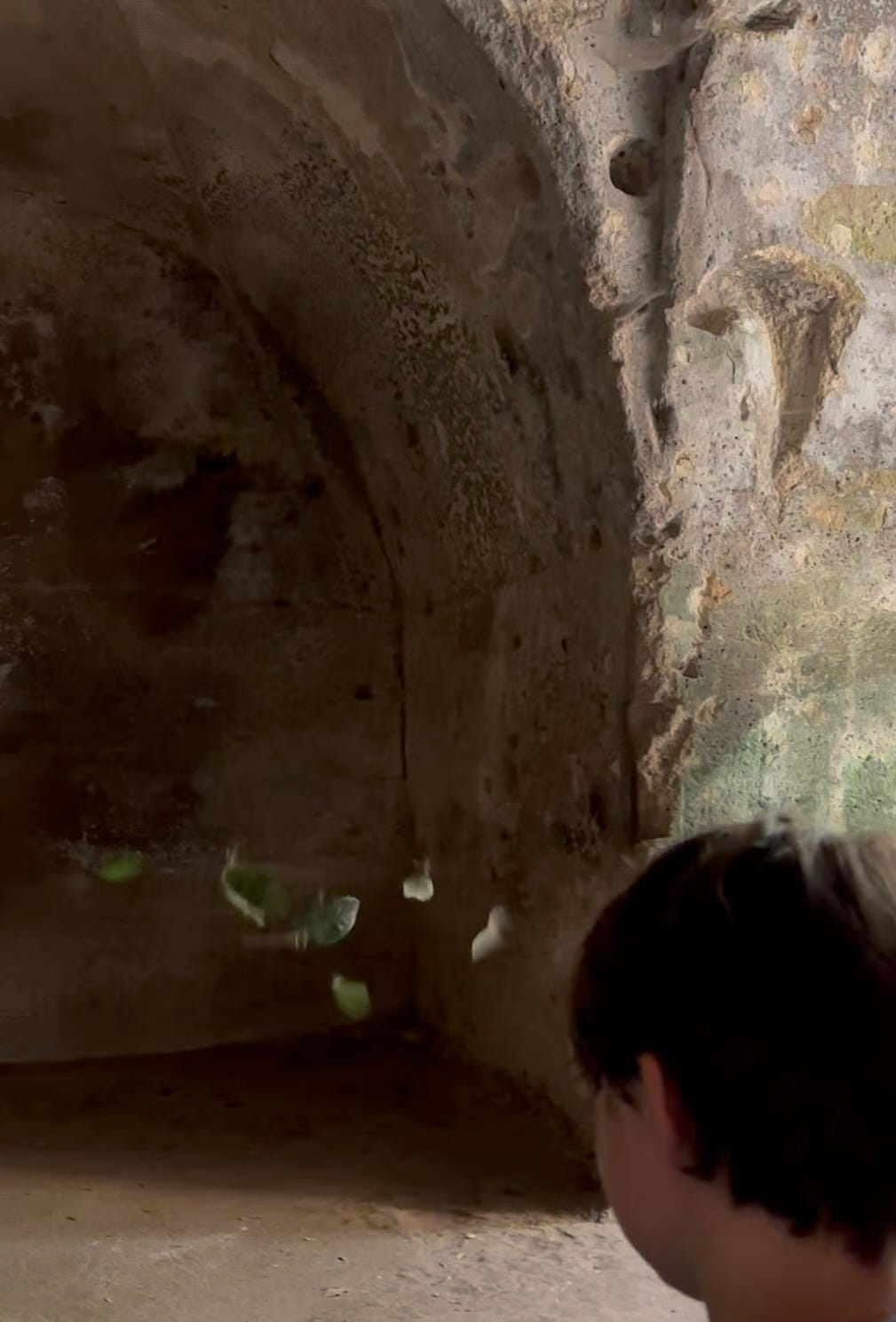

In the Aeneid, the Sybil of Cuma prophesies by “singing the fates,” and writing her words down on oak leaves. Often the leaves were scattered by the wind at the mouth of her cave, into a jumble of mixed-up words, which the Sybil refused to rearrange and interpret a second time.

After that it was up to the listener to make sense of nonsense. The answer blowing in the wind.

“The breeze in the trees,” la guida Andrea said as these thoughts ran through my head.

“Cuma” means.

He corrected himself, confessing to poetic interpretation, the license to rhyme. The etymology of “Cuma” is closer to: “the sound of the waves reverberating off the mountain”—one hypothesis, but la guida’s translation is better.

(The guide is a poet himself, in private, he later revealed. He tricked me. Reciting his own verse in the tomb of Virgil, as if it came from Virgil or someone else. Because it could have, because like all music, it does.)

In the Aeneid, the Cumaean Sybil serves as the hero’s guide to the underworld, where Aeneas visits his dead father for advice.

The entrance to Hades, according to Virgil, lay at the nearby crater of Avernus, (which explains the belief that the Cumaean Sybil’s prophecies, like the Delphic Pythias’, came from visionary gas).

Odysseus (Ulysses) also visited Avernus for the sake of prophecy. Odysseus carried a sacred coin in exchange for advice from Tiresias—the central prophet of Greek myth, who symbolically derived his foresight from snakes.

In one of many versions of the Tiresias myth, he sees two snakes copulating on the ground, which he strikes with his staff.

Hera, queen of the Olympians, was incensed by this act. She either blinded Tiresias on the spot, or turned him into a woman for seven years as punishment. Depending on the version.

Regardless, these were part of the Tiresias cycle, the symbolic source of his wisdom—disability and liminality. He was a psychopomp, like the Sybil: a mediator between the living and the dead for Odysseus.

After seven years, Tiresias encountered two snakes coupling again. This time he left them alone. The curse was lifted.

As one who’d experienced both sides of humanity, Tiresias was granted the dubious honor of settling an argument between Zeus and Hera, divine king and queen: Who derives more pleasure from sex, man or woman?

Each claimed the other did. Tiresias responded with some version of:

“When the ear itches, what feels better after the scratch, the finger or the ear?”

The ear. Who was incensed about losing this argument. Hera rewarded knowledge with punishment again—let’s say blindness, since the myths are many, and Tiresias remained blind for life, robbed of sight while gifted with foresight, while the gender spell was temporary.

The only archeological evidence of prophetic activity in Cuma, besides myths and caves, Andrea says, is a coin devoted to an oracle of Hera—this was news to me. Conflating the myth of Odysseus and Tiresias with that of Aeneas and the Sybil.

A relic from Homer’s Odyssey, and the hero’s visit to Tiresias at the entrance to Hades, the crater. Avernus.

The crater has been filled with water since Virgil’s time.

Lake Avernus, whose name translates to “without birds”—because birds auspiciously avoided the area. Probably due to toxic gas or frequent eruption.

When we arrived, Lake Avernus was an aquatic aviary dotted with floating seagulls.

In Virgil’s account, the Cumaean Sybil acts as a bridge between the land of the living and the the dead. She teaches the hero, as Virgil would later guide Dante through his Inferno, what Aeneas needs to know in order to survive his trip to hell and back.

The descent is easy,

Virgil’s Sybil says…

All night long, all day, the doors of Hades stand open.

But to retrace the path, to come up to the sweet air of heaven,

That is labor indeed.

The Sybil provides Aeneas with “the golden bough.”

A branch of golden oak which the poetically-influential mythologist Sir James George Frazer, in the nineteenth century, thought was plucked from a sacred oak grove of Diana at Nemi. Another crater, now a lake—Lake Nemus.

Frazer’s Golden Bough was a sacred stick of “holy wood” (Nemus). In mythical tradition, the golden bough granted a slave a right to the throne, through mortal combat with an aged king, should he pluck it and become victorious.

The leafy symbol of overcoming death, and rising above, that golden sprig of oak.

The archeological ruins of Diana’s temple, presumably the site of her sacred oak grove in Nemus, are outside of Rome. Another place I’d like to visit, but couldn’t.

As fate would have it, there is a sacred oak grove of Diana’s in Cuma… After a fashion.

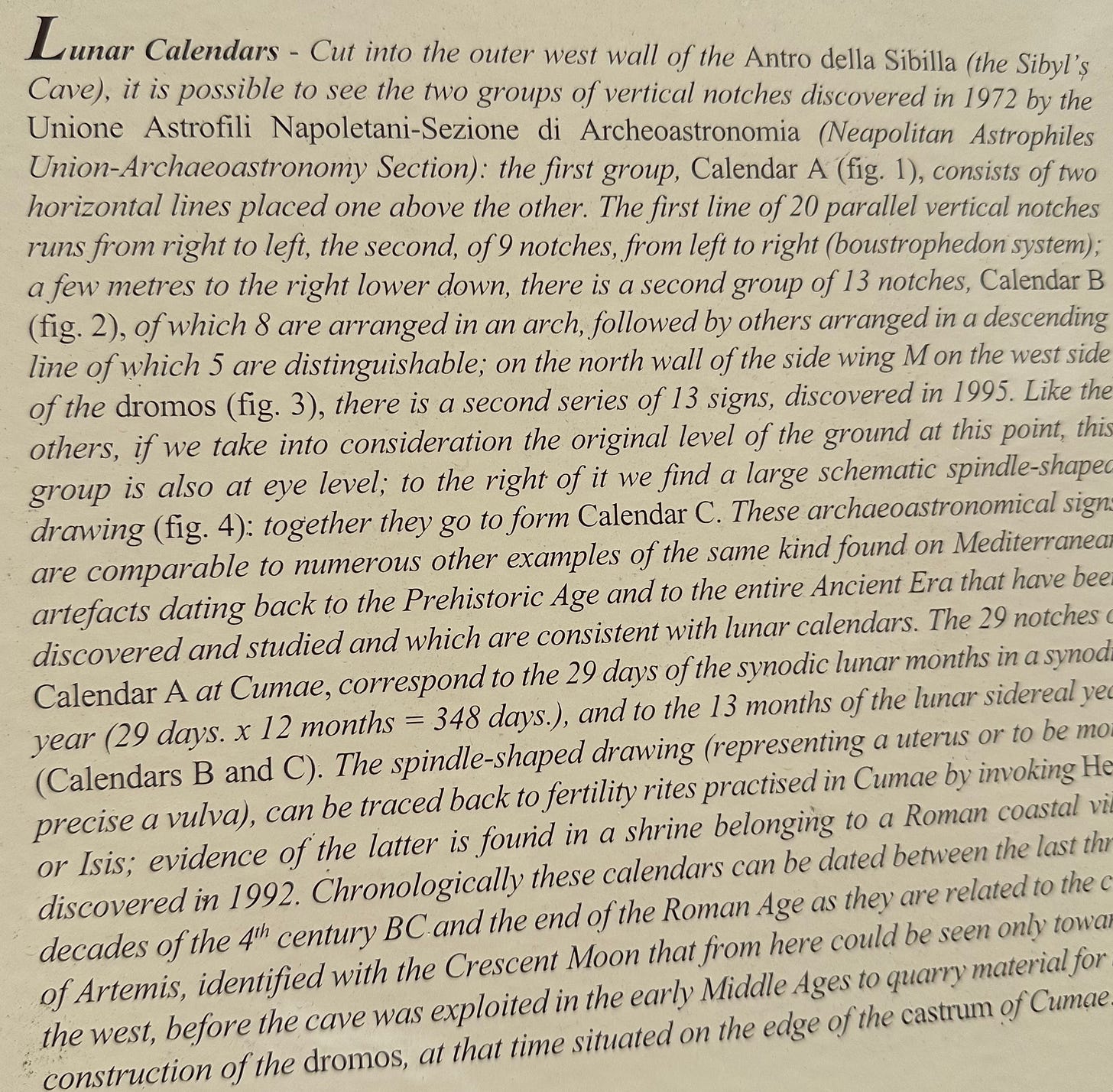

In the 1970’s—a century after Frazier’s Golden Bough—archeologists unearthed a lunar calendar outside the Sybil’s cave, suggesting the moon goddess, Diana (the Roman version of virgin Artemis), may have been present here as well.

Like Lake Nemi, Cuma is also surrounded by oak trees, and a volcanic crater lake, the one “without birds.”

In the verses of Ovid’s Metamorphoses—the book of changes—the Cumaean Sybil is granted one wish, by her patron deity Apollo, in exchange for her virginity.

Holding aloft a handful of sand, the Sybil wishes to live for as many years as there are grains of sand in her palm—then doesn’t hold up her end of the bargain once Apollo grants her wish.

Here the Sybil myths strangely overlap with one version of the Tiresias myth, during his seven years as the other sex. As a female prophet, Tiresias also refused the advances of Apollo.

In the end, the foreseer lacks foresight. Apollo takes his revenge by granting the Sybil’s wish, allowing her to live for a thousand years without sacrificing her virginity…

While her body grows old and decrepit. Because the Sybil forgot to ask for eternal youth as well as longevity.

The Sybil withers away, to the point she must be bottled in a jar to keep her shrunken bits and pieces in one place. At the end of her thousand-year lifespan, only her bottled voice remains.

The epigraph to T.S. Eliot’s poem The Waste Land, which was heavily influenced by James George Frazier’s Golden Bough, and partly inspired Bob Dylan’s “Desolation Row” in turn, quotes Petronius’ Satyricon:

“For I indeed once saw with my own eyes the Sibyl at Cumae hanging in her jar, and when the boys asked her, ‘Sybil, what do you want,’ she answered, ‘I want to die.’”

“‘Siri,’ what do you want?,” I want to ask.

This is all reminscant of a dystopian TV series (Black Mirror) riffing on Trans-humanism—the utopian tech religion that aspires to make humans immortal by preserving our memories and consciousness digitally—where humans find themselves imprisoned for all eternity in digital urns.

“‘Alexa,’ what does ‘Sybil in a Jar’ mean?”

The verses of Ovid’s Metamorphoses were composed just after the year zero, around the time proposed for Christ’s birth, alongside the ascension of Caesar Augustus—the first emperor of Rome.

The poem describes, through a series of pre-extant, re-worked myths, which all pertain to the theme of metamorphosis, the history of the world. From creation to the apotheosis of Caesar into a god.

(Ovid was subversive, but he wasn’t stupid. Flattering the emperor as divine was a career move.)

Ovid’s Metamorphoses is a book of wonders, suggestive of Darwinian morphology, keenly aware that the only constant in life is change.

Yet even amid the Heraclitean fire and flux, and the transfiguration of evolutionary biology, Ovid recognized that the old gods keep resurfacing in new forms.

Like Ovid rearranging ancient Greek myths into updated Roman ones, the particulars change, but their basic themes and relational structure remain the same (although the myths sometimes assume updated significance in the poet’s hands, in a new cultural context).

Like a transposed piece of music, the notes are altered, but their relation to each other remains, more or less, the old familiar melody in a new key. The Song Remains the Same.

Ovid was quite successful in his own time, as well-known as Virgil. Shortly after he completed his Metamorphoses, he was exiled to a small outpost on the Black Sea, by Augustus Caesar himself.

In Ovid’s own words, the offense for which he was canceled was, carmen et error, “a poem and a mistake”—as he wrote in his sorrows from abroad, the Tristia.

The particulars of that “poem” and that “mistake” are up for debate, but many believe that Ovid’s Ars Amoria (the “Art of Love,”), a poetic pick-up guide that celebrated adultery, probably had something to do with his exile.

The Julian Marriage Laws had recently been implemented, which codified monogamous marriage, to boost the Roman birth rate, making adultery a serious offense.

In his verse, Ovid also may have inadvertently insulted Caesar’s granddaughter Julia, who was not a strict adherent of monogamy herself (and was also exiled, for various potential reasons, including sedition as well as promiscuity).

Whatever the offense, Ovid lived the rest of his life in sorrow and exile, while his elder contemporary Virgil remained the Poet of State.

Virgil may have been influenced by Hebrew texts, according to the Roman historian and general Tacitus.

Constantine, the first Roman Emperor to convert to Christianity (and by extension, to convert the empire itself), cited the whole of Virgil’s pastoral Eclogues as a reference to the coming of Christ, and quoted the Sibylline prophecies in Virgil’s poem as evidence, during his first address to the Roman assembly.

In later years, the Cumaean Sybil and Virgil continued to be regarded as prophets predicting the coming of Christ, since the fourth book of Virgil’s Eclogues appears to contain a Messianic prophecy, which medieval Christians interpreted as Jesus.

By writing about a mythical prophetess, Virgil inadvertently became a “prophet” himself, influencing the future of religion and art. (This happens later with St. Augustine, the first confessional autobiographer, who added the concept of original sin to Catholic doctrine, and Dante, who invented purgatory in The Divine Comedy.)

This is one reason Dante Alighieri chose Virgil to be his guide through the Inferno in the Divine Comedy, just as Virgil had chosen the Sybil to be Aeneas’s guide to the underworld:

“Poets are the unacknowledged legislators of the world.”

—Percy Bysshe Shelley

During the Italian Renaissance, Michelangelo featured the pagan Sibyls of Delphi and Cuma prominently among his Old Testament prophets on the Sistine Chapel ceiling.

I saw them the other day, pagan fortune-tellers floating above me in the mecca of Christendom, flanking the Tree of Knowledge. Among the throngs of people, the only solace was mandated silence for Mass, concluding with an English translation in the Sistine Chapel:

“World without end, forever and ever, Amen.”

The Sybil keeps reappearing: in the twentieth century, in T.S. Eliot’s Waste Land; in Robert Grave’s fictionalized history of the Julio-Claudian dynasty, I, Claudius (1934) (and the 1970s made-for-TV series adaptation). In Sylvia Plath’s semi-autobiographical novel, The Bell Jar.

In The Sopranos, one of the most literate and entertaining television series from the turn of the millennium, Anthony Soprano takes a business trip to Naples, to network with the Cosa Nostra, only to discover that the mafia’s male capo di tutti i capi have all killed each other off or gone to prison.

The New Jersey mob boss slowly realizes he must negotiate with the last remaining Neapolitan boss, who’s gone senile, through his beautiful but spooky wife, who is de facto the only surviving mafia Don(na).

The Bella Donna fully subscribes to magical superstitions about imitation and contagion; Tony watches her collect her own toe nail clippings, ordering her pedicurist to burn them after she clips them, because she doesn’t want anyone using these pieces of herself against her.

She takes Tony to the Sibylline caves, and explains how the prophetess breathed the vapors to induce visionary insights, standing over the volcano vents at the gates of hell in all her dark, pre-Raphaelite beauty, a surrogate Sybil in millennial Naples. Like the secular modern version of a priestess—the psychiatrist—she reveals to Tony what he can’t see and may not want to hear.

She reminds him of his mother. (“Livia,” who shares her name with Caesar Augustus’ wife.)

The Sybil even time travels to the end of the twenty-first century, from the beginning of the nineteenth.

In the introduction to Mary Shelley’s post-apocalyptic novel The Last Man (1826), the author claims she derived her story from a visit to the Cumaean Sybil. The bones of her future novel were supposedly discovered on painted oak leaves, during a visit to Cuma eight years earlier in 1818.

Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley, who conceived Frankenstein at the age of eighteen—a prophetic tale about the unforeseen consequences of scientific hubris—spent several months around Naples in 1818.

“A paradise inhabited by devils,” she called the city. A quote misattributed to herself, to the father of German Romanticism, Goethe, to many others, and no one in particular.

Who knows such things. The true source doesn’t exist in any one place. The phrase “Napoli è un paradiso abitato da diavoli” is common knowledge in Italy. Depending how one feels about “devils.”

Shelley came to visit the shadows of Cuma’s Sybil in a state of loss and chaos, after the death of her two children with husband Percy Bysshe Shelley (1792-1822). She descended into depression, driving the libertine Romantics apart for a time.

As her husband sought the agreed-upon solace of another’s arms, Percy wrote:

My dearest Mary, wherefore hast thou gone,

And left me in this dreary world alone?

Thy form is here indeed—a lovely one—

But thou art fled, gone down a dreary road

That leads to Sorrow's most obscure abode.

For thine own sake I cannot follow thee

Do thou return for mine.

By the time The Last Man was published, Mary’s husband had been dead four years, drowned off the coast of Tuscany in a shipwrecked storm. His remains and relics are in Rome, along with those of another Romantic, John Keats.

Edited into the first-person narrative of a man living at the end of the twenty-first century—our time, coming soon to a theatre near you—Shelley’s Sybilline vision in The Last Man proves to be the end of humanity, after a plague.

Remember, there are many Sybils. The name is a titular position, like “bishop” or “priestess,” as well as a recurring mythical figure hiding behind various names that are too heretical to mention now… (one of them shares a first name with the author of Frankenstein).

Ingrid Bergman tread these same halls. As Katherine Joyce, a woman drawn to local museums and ancient ruins like the Sybil’s. Transfixed by a disturbing fascination, finding herself in communion with Italian art and history, she’s introduced to another way of life, on her journey to Italy.

In 1949, while filming Stromboli (set on the volcano for which Woody Guthrie wrote her a song), Bergman fell in love with director Roberto Rossellini. She became pregnant, and divorced her husband to elope with the Italian auteur. Both were married at the time, and left to make arthouse cinema together for five more films.

A major scandal in the American press. Bergman was denounced by Hollywood, the Senate, and even Lucky Luciano (in a 1953 interview with the exiled mobster conducted at the Hotel Vesuvio).

Bergman spent the next six years in self-exile, making auteur films with her new husband, sacrificing Hollywood success to experiment with Italian neorealism.

In 1954, the Italian-American couple shot Journey to Italy, a film about an English couple slowly drifting apart as they tour the peninsula. Three years later, the actress and director drifted apart themselves, and Bergman returned to the good graces of Hollywood.

Some of the visitors here are real, some are characters. But every hopeless romantic with the means-and-inclination has visited the Sybil’s chambers, and the ruins of Apollo’s Temple above, since before Romanticism was a twinkle in Goethe’s eye.

Including Aeneas, of course, who wandered here after the fall of Troy, consulted the Sybil, plucked a golden bough of oak to protect him on his descent to Hades, then returned safely from the land of the dead to sail north and lay the mythical genes of Rome.

So the story goes. According to the Eggman, Virgil, in his imitation of Homer’s Odyssey, The Aeneid.

Even the Sybil in a jar is long gone. The woman who lived for a thousand years died two thousand years ago. So my guide Andrea and two Italian donne I bumped into at the cave entrance will have to do.

There are two potential sites for Apollo’s Temple, unearthed so far. Andrea and I dragged my son halfway up the acropolis, to the first. The climb nearly killed him, so I suggested the guide slowly escort my son to the mouth of Sybil’s cave in the shade, while I ran up to the site above.

Both sites were ancient Greek temples, then Roman ones, then Roman-Christian churches. The tombs below are likely from post-Constantine churches.

In ancient Italy, usually the lower a structure is, the older. But in Cuma the higher one had the buzz. Aswarm with bees and oak—the tree of Jove (i.e. Jupiter, who, it turns out, this latter site is identified with, not Apollo). For my purposes at the time, it was the One closest to the Sun.

Unlike the lower temple ruins, the upper site contains a sacred circle.

Uncertain of its vintage or creed, Greek or Roman, pagan or Christian, I laid my hand to it, and said something lost in the breeze of the trees.

On the way out, plucking a spray of oak, I passed through the portal to meet my guides below.

In the Hallways of Always. Where Andrea and my progeny were waiting in the cool corridors beneath the Temple of the Sun.

One Sybil approaches below—one of two of Italians I passed on the way in, who asked me to take their photo.

It was cool inside. The air smelled sweet and strange, but it was still. Nothing to scatter oak leaves. I let my son play the breeze.

After I laid my own to the floor.

According to la guida, the Sybil’s obscurant fortune-telling sounded something like this. Andrea playing Virgil, in a game of telephone between one generation and the next.