Pandora's Box: a brief history of the "magic mushroom" in American pop culture

A few months ago, I spotted a peddler most strange. Like Jack going to market for to sell the family cow, I encountered a crier selling what might as well have been magic beans.

Or something equally unregulated.

Mushroom vendors are a staple at Northwest farmers markets this time of year, when chanterelles, which can only be harvested wild, come into their own. But as I waited in line for a breakfast burrito next to this mystical hawker, I noticed the accoutrements of the typical forager were missing—most conspicuously, the baskets-ful of oysters, chanterelles, porcini, and other fungus normally on display. This peddler sat behind an empty card table, casually thumbing a book, with little to advertise her wares. There was a small bag at her feet, hardly spacious enough to accommodate a bushel of beans, adorned with the laminated red-and-white mushroom emoji from Apple, Inc. As I collected my sausage-and-egg with hatch-chile salsa, I sauntered past her tiny formica tabletop, where curiosity got the better of me.

“What-ah… kinda mushrooms you got there?” I inquired, half-knowingly.

“Oh, you know,” she pierced me without batting an eye. “The fun kind.”

Peering into her bag, I noticed it shone like gold—filled with what looked like homemade Willy Wonka bars, each wrapped in the color of a golden ticket.

“Ah,” I understood, and went to consume my burrito.

A week later, the vendor was gone.

Strictly speaking, this sort of self-promotion remains illegal. Even in the state of Oregon, where much harder substances are in legal limbo. In November 2020, voters authorized the therapeutic use of psilocybin—the active compound in so-called “magic mushrooms”—to be administered in a clinical setting, when Oregon Measure 109 passed. On the same ballot, the ensuing Measure 110 decriminalized all drugs, including fentanyl, to arguably-disastrous consequences.

I have few reservations about the disappearing bean-saleswoman at the farmer’s market, whose advent I didn’t foresee; I have many more about the clinically-approved model to come. Here’s why (aside from the idea of combining all the fun of the therapist’s couch with hallucinogens, or adding to the smug self-certainty of patients who’ve “done the work,” the zeal of the psychedelic convert).

Clinically-approved articles like this: “Inside the Movement to Decolonize Psychedelic Pharma.” In which the author (from the same demographic that ruined the publishing industry) explains how, “As Western medicine brings psychedelics into mainstream use, a growing movement is innovating new business models grounded in reciprocity and inclusion.” What could be a happier marriage than “business models” and “decolonization?” With all the quirky, institutional language that united the ivory tower, corporate America, and DEI struggle sessions a few years back?

As “Decolonize Pharma” makes clear, psychedelic therapy is poised to be big business. Johnson and Johnson have their own proprietary blend of Ketamine. Compass Pathways, a psilocybin research and therapy company backed by venture capitalist Peter Thiel (PayPal, Facebook), earned a billion dollar post-IPO valuation. Sam Altman, recently ousted, then reinstated in a corporate power struggle at OpenAI, bet on one company devoted to reciprocity, inclusion, and Indigenous acknowledgement, Journey Colab—so that’s reassuring. Even former Texas governor Rick Perry, who once forgot the name of the government agency he was pegged to run, has gotten in on the so-called “psychedelic renaissance,” arguing for the use of MDMA to treat PTSD in veterans.

In a mental healthcare industry that’s made little progress in novel treatments over the past 50 years—and whose current treatments are generally agreed to be woefully inadequate—the market potential of psychedelic medicine is clear. The psychedelic drug market is projected to grow at more than 16% annually and reach $6.85 billion by 2027, with a potential $100 billion market opportunity.

—“Decolonize Psychedelic Pharma”

The industry that finally admitted another billion-dollar sector, Selective Serotonin Re-uptake Inhibitors (SSRIs), are worthless in the treatment of anxiety and depression (and may in fact exacerbate the problem) are now overseeing the mass production of LSD, MDMA, Psilocybin, Ketamine, and other psychedelic compounds. Genuflection, mindless platitudes, and reciprocity-and-inclusion committees have seemingly unlimited potential for growth.

As a cautionary tale, I remind readers how psychedelic mushrooms went from limited ritualistic use in Oaxaca, Mexico to the world stage. Even in the hands of Western ‘colonizers’ whose sense of literary and cultural imagination dwarfs that of, say, Peter Thiel, Sam Altman, or Rick Perry, the consequences were disastrous for one woman at the mercy of a J.P. Morgan banker, the Mexican government, her own community, and the CIA.

I’m still tempted to argue the results were more creative than whatever Big Pharma, or the author of “Decolonize [Big] Pharma” have in store by 2027.

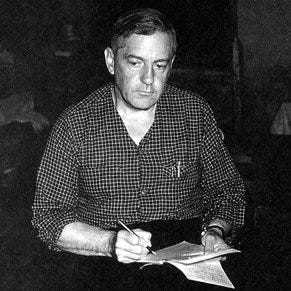

This is Robert Gordon Wasson, Vice President for Public Relations at J.P. Morgan. He hated mushrooms:

"Like all good Anglo-Saxons, I knew nothing about the fungal world and felt that the less I knew about those putrid, treacherous excrescences the better."

That is, until Wasson’s Russian-American bride, a doctor, took him foraging in the Catskills for their honeymoon in 1927, when Wasson became an amateur mycologist. He published a book on the subject with his wife, Mushrooms, Russia, and History, which ran in Life magazine in 1957.

The same year, Life released a photo essay by Wasson, “Seeking the Magic Mushroom”—whence the now-ubiquitous term, the brainchild of a Life magazine editor, “magic mushroom.” (Wasson objected to the term.)

In 1955, R. Gordon Wasson and his photographer became, in Wasson’s words, "the first white men in recorded history to eat the divine mushrooms" of Mazateca. When his account was published in Life magazine, a generation of thrill seekers and curious psychonauts—among them Timothy Leary and author Tom Robbins—became interested in the small town of Huautla de Jiménez in the Sierra Mazateca mountains of Oaxaca, Mexico, and the region’s “magic mushrooms.”

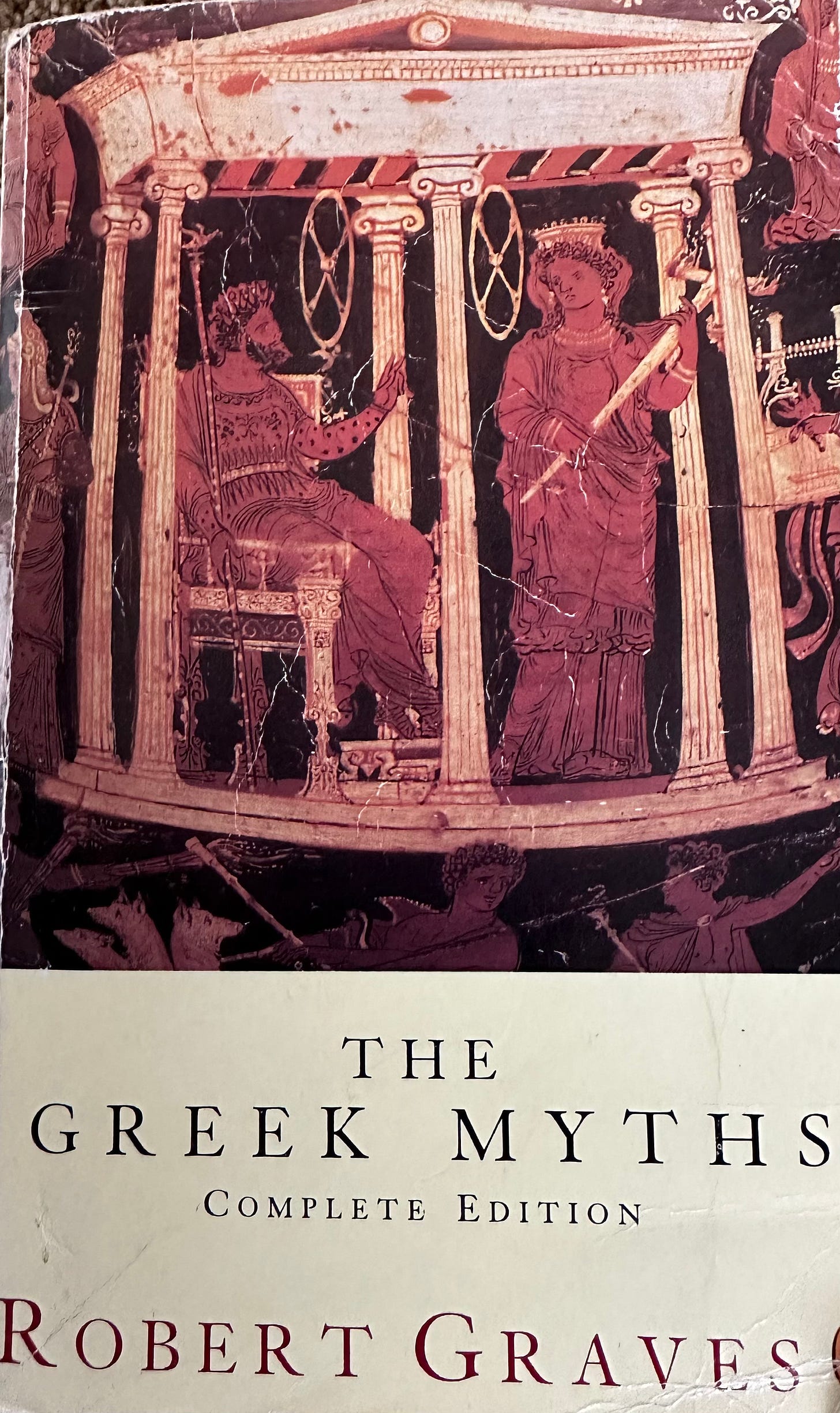

The Wassons—R. Gordon and his pediatrician wife Valentina, were alerted to the presence of psychedelic mushrooms in Oaxaca by the English poet and literary theorist Robert Graves. Graves, a bit of an eccentric, was a student of comparative mythology who wrote famous books like The White Goddess (about a recurring figure in myth, not white colonizers) and, after hearing from the Roman Emperor Claudius in a dream, a series of historical novels, I, Claudius—which remain a classic of 1970s television, in the adapted-for-TV miniseries.

Graves sent the Wassons a letter containing an article about the ritual use of sacred mushrooms by Mesoamericans in the 1500s, which eventually led to Wasson’s expedition to Oaxaca and his essay in Life magazine. Graves’ letter quoted Harvard biologist Richard Evans Schultes, now considered the father of ethnobotany.

Among other people, Schultes influenced E.O. Wilson, Aldous Huxley, William S. Burroughs, Allen Ginsberg, Timothy Leary, Carlos Castaneda, and anthropologist Wade Davis, a student of Schultes who went on to write a seminal study on the state machinations of Haitian voodoo that explained the phenomenon of zombiism by linking it to a neurotoxin derived from the pufferfish, The Serpent and the Rainbow: A Harvard Scientist's Astonishing Journey into the Secret Societies of Haitian Voodoo, Zombies, and Magic (1985).

Schultes, however, was often derisive of his unwanted countercultural step-children (lamenting that Timothy Leary couldn’t spell many of the Latin names for plant species he cited in his own work). When William S. Burroughs imparted to Schultes the metaphysical insights he’d experienced on ayahuasca, the Harvard botanist replied sardonically, “That’s funny Bill, all I saw was colors.” He was a character and an anglophile, beloved by his students, who often voted for the Queen in American elections because he claimed not to have supported the American Revolution. Schultes was the first to research the lost psychedelic mushrooms of Mesoamerica (lost to European knowledge, after their use was discouraged by Spanish monks). His best-known work, written with Albert Hoffman, the chemist who first synthesized LSD, was The Plants of the Gods: Their Sacred, Healing, and Hallucinogenic Powers (1979).

However it came to pass that R. Gordon Wasson, a J.P. Morgan exec, received a letter from an eccentric English poet named Robert Graves, referencing the work of pioneering ethnobotanist Richard Evans Schultes, Wasson was intrigued. He and his wife set out for the hills of northern Oaxaca, with financial assistance from the Geschickter Fund for Medical Research. What Wasson didn’t realize was, the Geschickter Fund was financed by CIA psychedelic research, the agency’s “mind control” program, MK-Ultra—which would eventually, and unwittingly, inspire much of the countercultural revolution in the U.S. through a series of volunteer Guinea pigs that included author Ken Kesey, poet Allen Ginsberg, Grateful Dead lyricist Robert Hunter, and most terrifyingly, perhaps Charles Manson. There were countless involuntary MK-Ultra test subjects as well, including American prisoners, and unsuspecting subjects drawn from the agency itself.

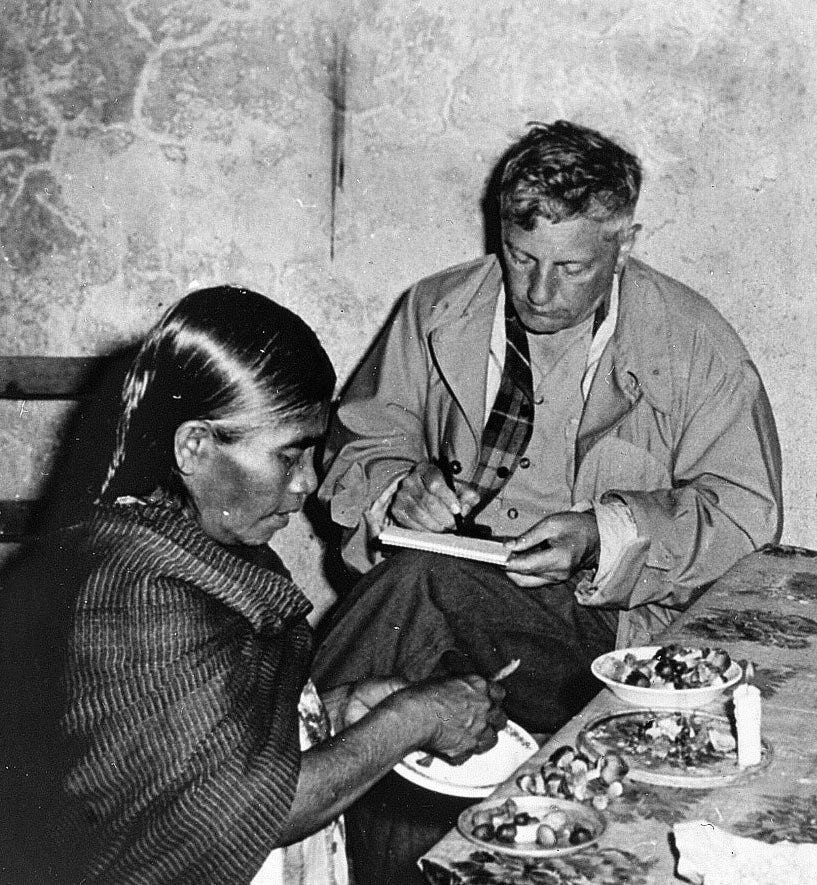

Wasson’s contact in Oaxaca was a campesino woman named María Sabina, an illiterate peasant curandera, singer, and oral poet practicing indigenous Mazatec medicine, who used psilocybin for healing purposes (she also, according to some accounts, combined Mazatec spirituality and mushrooms with the veneration of Jesus, Mary, and Catholic saints, in an instance of religious syncretism reminiscent of the Eucharist, which is precisely what disturbed Spanish monks in the 16th c.).

Using subterfuge—telling María Sabina he and his wife were trying to locate a missing son—Wasson convinced the shaman to allow him to participate in a healing ceremony that included the ingestion of psilocybin. He also vowed not to identify María Sabina or disclose the particulars of her practice, an unkept promise he came to regret.

In the years following the 1957 publication of “Seeking the Magic Mushroom” in Life, a wave of spiritual seekers descended on Huautla de Jiménez—including, by some accounts, members of the Rolling Stones, the Beatles, Bob Dylan, and Walt Disney. Wasson’s ‘discovery’ led to the synthesis of psilocybin by Albert Hoffman in Europe, and proselytization of the drug by Timothy Leary in America.

The genie was out of the bottle.

As America and the West turned-on, María Sabina suffered. The Mexican authorities, overwhelmed by rucksack wanderers, accused her of drug trafficking. The locals accused her of selling out their cultural secrets. Her house was burned down, and her son murdered. The pharmakeus (healer) became pharmakos (scapegoat). And the erstwhile cure, psilocybin, was now regarded as poisonous to the local community—pharmakon.

Today María Sabina is regarded as a regional hero, and a cautionary emblem of cultural exploitation.

R. Gordon Wasson, the former banker, went on to postulate the use of psychoactive mushrooms in Russia, in Siberian shamanism, in the Vedic scriptures of India, and in the ancient Greek fertility cult of Demeter and Persephone—the Eleusinian Mysteries. In 1978, he published a tract coauthored with Albert Hoffman of Sandoz laboratories and Boston University classicist Carl A.P. Ruck, The Road to Eleusis: Unraveling the Secret of the Mysteries, suggesting that the ecstatic initiation rituals of Eleusis involving the potion “kykeon,” mentioned in Greek texts from Homer onward, were contaminated with Ergot, a naturally-occurring fungal version of LSD. Tests of ancient Greek drinking vessels have since confirmed the presence of the compound in several places.

Robert Graves, the English poet who alerted R. Gordon Wasson to the ritual use of hallucinogenic mushrooms in Oaxaca, hypothesized that the Eleusinian Mysteries involved the use of psychotropic mushrooms eighteen years earlier, in 1960.

There were unintended consequences to the unveiling of psychedelic mushrooms in Oaxaca, Mexico, and their exportation to the world at large, to say the least. A banker and his wife mixed-up in the CIA’s mind-control program. A curandera poet suffering the loss of her son, community, and home. A “generation of permanent cripples, failed seekers, who never understood the essential old-mystic fallacy of the Acid Culture: the desperate assumption that somebody... or at least some force - is tending the light at the end of the tunnel,” as Hunter S. Thompson put it.

That was the fatal flaw in Tim Leary's trip. He crashed around America selling "consciousness expansion" without ever giving a thought to the grim meat-hook realities that were lying in wait for all the people who took him seriously... All those pathetically eager acid freaks who thought they could buy Peace and Understanding for three bucks a hit.

Still and all, it sounds better than paying Johnson and Johnson $590 for a hit of Spravato, its Ketamine-derived depression treatment, when the generic version costs $11.99.

And I’d rather have Robert Graves, Richard Evans Schultes, María Sabina, or even a reformed J.P Morgan exec, tending the light at the end of the tunnel than Sam Altman, Peter Thiel, or the author of “Decolonize Psychedelic Pharma.” At least the former proved these substances exist across cultures, rather than belonging to a select beleaguered few, whom the new gatekeepers appeal to as they take exploitation public.

In short, when it comes to pop spirituality, give me botanists, anthropologists, poets and musicians. Leave the biotech, AI engineers, and venture capitalists to Wall Street.