In the final installment on “#witchhunts,” I turn to the primitive origins of scapegoating for insights on imitation, victimhood, and the psychology behind one of humanity’s strangest practices.

(Part I constituted a case study in modern cancelation; Part II glossed the history of Early Modern witch hunts compiled in Charles Mackay’s Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds (1841). Part III looked at two of America’s great scapegoating texts, The Scarlet Letter and The Crucible.)

There were numerous figures in cancelation campaigns, high-profile and not, after the movement that seemed to inaugurate the cancel-culture era in 2017, #MeToo.

The first story I covered in this series (here) was localized (in Portland, OR), but it demonstrates how individuals can become engulfed by grander social movements—just as Europe was engulfed in a fever of witchcraft accusations that spread from the faculty of Cologne to the farmers of colonial New England. In the case of the local writer I covered, she was ensnared merely for observing and critiquing one aspect of such a movement—taboo at the time.

Covering the story of Nancy Rommelmann third-hand—writing about a journalist whose career in Portland, and her husband’s, were destroyed because she reported the story of dubious #MeToo spokesperson Asia Argento—I confess I felt a little tainted by association.

That story, like the ensuing cancelation of Rommelmann, was a petty, sordid affair; writing about it left me feeling somehow contaminated. And in fact, this is the functional metaphor and mechanism of ancient scapegoating: contagion.

Or, as the Greeks referred to the concept of infectious bad influence, “pollution.”

It’s no coincidence, I think, that the modern corollary to this sort of behavior reached a fever pitch during a global influenza—disseminated by the viral copying machine of social media.

Putting aside legitimate offenders brought to trials of public opinion during and after #MeToo, the viral contagion most feared by the deciders of what was right and good at the time was, the spread of poisonous, or “toxic” ideas.

Challenges to authority, or popular opinion—whether the accepted wisdom was about COVID-19, #MeToo, or a number of other social justice issues.

In Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds (1841), Charles Mackay, chronicling the history of “The Witch Mania” in the sixteenth century, wrote:

“From the best authorities, it appears that the Hebrew word, which has been rendered venefica and witch, means a poisoner and divineress, a dabbler in spells, or fortune teller.”

I’m tempted to think of the contingent of canceled, or ostracized, liberal-minded thinkers and journalists (many of whom inform these articles and inhabit this platform)—whose heretical observations during the pandemic are finally being legitimized by legacy media like the New York Times—as dabblers in written “spells” or “diviners” of future opinion, which is only now beginning to look like popular consensus.

But back to “poisoners,” and toxic “pollution.”

The earliest pre-Christian witch trial on record, circa 323 BC, concerned a woman named Theoris of Lemnos. In a trial speech delivered by the Athenian statesman Demosthenes, Theoris was described as miaros (“polluted”), mantis (a “seer”), and pharmakis (a provider of drugs or poisons). These descriptions comport with those given by Mackay, derived from ancient Hebrew, of “poisoner” and “divineress,” in Popular Delusions.

Theoris was also charged with asebeia, or “desecration and mockery of divine objects.”

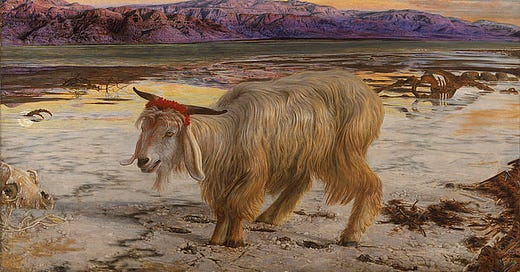

What we see in these descriptions is an overlap between Greek and Hebrew, and between Early-Modern conceptions of the “witch,” such as those we encounter in the sixteenth century, and an earlier predecessor, the scapegoat (also from a Hebrew word, in the book of Leviticus, describing an actual goat, ritualistically exiled into the wilderness, with the sins of the community written on pieces of parchment attached to the animal).

As I’ve discussed elsewhere (here), the concept of the scapegoat - a figure sacrificed for the good of society - as far as ancient Greek is concerned, revolves around a root word, pharma.

Pharmakon, as linguistic philosopher Jaques Derrida famously applied to the act of writing, is a slippery term that means both “poison” and “cure.” In the record of her trial, Theoris of Lemnos is described as a pharmakis, variously accused of poisoning, or trying to heal, someone with drugs.

Pharmakeus means “healer,” or “magician”—a medicine man (or woman - or as was often the case, someone symbolically in-between).

Pharmakos means “victim,” a ritual sacrifice, or exile from the community—a scapegoat.

The only way to reconcile these three sets of meanings under a single heading is to connect the scapegoat to a related figure, the shaman—the first instance of hierarchy and specialization, a social role distinguished from the rest of society. The shaman, by virtue of this distinction, is inherently an outsider. In addition to charges of impiety, and being a pharmakis, Theoris had the added sin, and prerequisite, of being an outsider—someone foreign to Athens, from Lemnos.

A pharmakeus, or shaman, performs music and dance, administers drugs or potions, and purports to heal a community through magic rituals, most of which are based on imitating the desired results of these rituals through art—a dance signifying rain, a mask or painting representing animals desired for food and resources, etc…

Or, a figure representing the toxic evil to be expelled from a community during times of hardship. Even a human being.

The shaman and the scapegoat converge in the act of supposedly healing society. In times of duress—plague, scarcity, or violent unrest—either figure could be relied upon to solve the problem through divine intervention, or at least pretend to, with the complicity of their community.

In some cases, the shaman literally becomes a scapegoat, or victim.

Franz Boas, one of the pioneers of modern ethnography, while studying the Kwakiutl Indians of British Columbia in 1966, observed that, a “great part of […] shamanistic procedure is based on fraud”—on artifice and illusion. As author Stanley Walens, also observing the Kwakiutl in 1981, noted, while these “shamans are admired for their legerdemain, if a shaman bungles one of these tricks, he is immediately killed.”

A clumsy pharmakeus (magician), in other words, quickly becomes a pharmakos (victim).

In the last installment, about Arthur Miller’s The Crucible, I mentioned Tituba, a Barbadian slave who conducts a magic ritual in the forest with the girls of Salem, which sets in motion the Salem witch trials. Tituba, an outsider to the Puritans based on a historical figure (originally Native American), was among the first to be accused of witchcraft in Salem.

As some musicologists have argued, the entire Early-Modern notion of “witches” was likely directed at individuals, especially women, practicing earlier, pagan rituals, outside the scope of the church—many of which concerned love and eroticism, and involved music. In Arthur Miller’s screen adaptation of The Crucible, appropriately enough, Tituba’s all-female aphrodisiac ceremony is accompanied by drums, dancing, and partial nudity.

The pharmakeus, that ancient predecessor to the artist or performer, like the pharmakos or scapegoat, occupies an ambivalent place in the public imagination—a marginal, or “liminal” figure, as anthropologists describe such individuals, including that mythical troublemaker, the oldest literary archetype known to man, the Trickster or troublemaker.

The scapegoat, in ancient Greek, as the trial record of Theoris illustrates, was routinely described as miaros, “polluted,” a profane contagion to be expelled. At the same time, paradoxically, the scapegoat is also revered as sacred, the food of the gods (ambrosia), who heals the community through their death or expulsion.

“The cause of, and solution to, all of life’s problems,” in the words of a popular animated series, describing another pharmakon, alcohol.

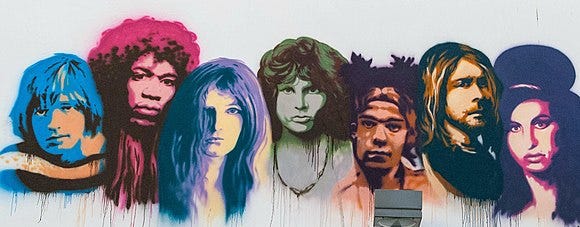

In similar fashion, modern society ambivalently reveres its popular artists, only to celebrate their premature demise—most often, through the artist’s pharmakon of choice.

Some of these inebriates are even pretentious enough to consider themselves “shamans.”

Pretension, of course, is the whole point: pretending - or reaching - for something that isn’t there, something beyond ourselves—one definition of the sacred, according to religious historians like Mircea Eliade and sociologists like Émile Durkheim—the reason we celebrate these self-destructive icons most, in spite, or because of, their buffoonery and disfunction.

The sacrificial-artist trope is so ingrained that another popular animated series parodied it, in an episode that aired after Britney Spears’ paparazzi downfall, during the ascension of her replacement, pop star Miley Cyrus.

More directly, South Park was parodying Shirley Jackson’s macabre short story The Lottery (1948), in which a victim from small-town America is chosen at random to be the annual human sacrifice ensuring that year’s harvest—which, if you’ve read any of The Third Ear, you may recognize as the symbolic framework for various world religions: fertility rituals around a dying and resurrected god.

On a more literary note than South Park, Franz Kafka’s animal allegory Josephine the Singer, or the Mouse Folk (1924) depicts Josephine, a singing mouse uneasily revered by her community (which alternately loves and mocks her histrionic performances), who then disappears from the face of the earth so that the rest of the “mouse folk” may prosper. Kafka was describing his own Jewish community in the years before World War II, scapegoats sine qua non, but the way he describes Josephine, she could easily be a stand-in for Britney Spears—just try googling images for “Josephine the Singer”.

This is all to say that, as a society, at the scale of the crowd, we have a conflicted relationship with ‘artists’ (loosely speaking), or celebrities, which borders on love/hate. They become scapegoats for any number of societal ills—gun violence and gangsta rap, Marilyn Manson and Columbine, heavy metal and the “satanic panic”of the 1980s, spring to mind.

But of course, one needn’t be an artist to embody the scapegoat. One could just as easily be a journalist, a politician, or a fool.

Along with The Crucible, in the last installment I discussed Nathaniel Hawthorne’s The Scarlet Letter. How the lowly scapegoat Hester Prynne—renowned for her artistry with a sewing needle, someone whose craftsmanship is coveted by Boston’s upper crust—becomes the center of attention on “Election Day” in Boston.

Because of her adulterous past, the townspeople ridicule Hawthorne’s protagonist, who wears a bright red mark of shame. At the same time, they find Hester a bewitching spectacle they can’t avert their eyes from. Hawthorne’s crowd is similarly mesmerized by other “sinful” social outcasts, like drunken sailors and “heathen” Native Americans, who visit Boston from the hinterlands on this one day.

The entire climax of “Election Day” is an example of the carnivalesque, a literary mode based on actual medieval Carnival rituals, which were in turn based on earlier pagan “inversion rituals,” as anthropologists describe such festivities, such as Roman Saturnalia—a midwinter holiday designed to ensure the coming of spring and the emergence of plants from the ground, in which the lower classes switched places with Roman elites for the duration of the holiday, in imitation of this seasonal inversion, the death and rebirth of vegetation, and return of the sun.

In Rome, slaves symbolically traded places with masters. Catholic Carnival boasted a “Boy Bishop,” or symbolically placed a Fool on an imitation of the King’s throne. In one celebration, it’s even rumored that an ass was led the pulpit to deliver a sermon.

In The Scarlet Letter, an ostracized Hester Prynne trades places with her secret lover, the esteemed Reverend Dimmesdale, who then dies of guilt for their sins. And of course, this substitution takes place on Election Day, when one patriarch steps down, and another ascends, to rule over the township of Boston.

Scapegoating, like its gruesome predecessor human sacrifice, is also an inversion ritual, in which a polluted victim is raised to the level of sacred offering, and a revered figure is brought low by death or exile.

In sublimated, symbolic form, such as Saturnalia or Carnival, the sacrificial inversion ritual is a form of provisional, controlled chaos, ultimately designed to reinforce the social order after it’s concluded—in the case of the latter, it was traditionally presided over by a “Lord of Misrule.” But symbolic violence and chaos can quickly slip in-and-out of the real thing, in a carnival atmosphere where rules are suspended and “Fools” hold sway.

It was jarring to say the least, when, looking for examples of scapegoating and the carnivalesque in literature, I happened to re-read the climactic event of The Scarlet Letter—“Election Day”—shortly after the midwinter events of Jan. 6, 2021. To recall that a rickety gallows—regicidal? a joke?—was erected for the Vice President, while its constructors howled “Hang Mike Pence!” That a protestor put his boots up on the Speaker of the House’s desk. That the media’s Lord of Misrule, clownishly dubbed the “QANON Shaman,” mounted the Senate dais, where he delivered an impromptu sermon, in what was, in his words, “like, the sacredest place.” It was an event characterized by politicians and media from both sides of the political divide, for competing reasons, whether to denounce or downplay the chaos, as a “carnival.”

Call it cosplay, call it a coup, it’s hard to ignore the parallels between Carnival and this half-conscious inversion ritual around “Election Day”—by nature, a transitional period of instability and uncertainty—when members of the maddened crowd usurped the place of America’s ruling class for several hours, as leaders huddled on the House floor. The president of the Senate climbed a symbolic scaffold in effigy, while a “shaman” sank behind his desk in the Senate.

The fact that Americans still can’t agree on how to categorize this topsy-turvy event—insurrection? protest? photo op?—speaks to its ambivalence, the thin line between carnival/violence. But as both the Vice President (the “Traitor”) and the QANON Shaman (the media emblem of Capitol-riot prosecution) must know by now, in such an atmosphere, one can easily go from being loved to hated, or vice versa.

To put it another way, in a carnival atmosphere, one can easily become: the scapegoat.

A similar ambivalence is documented in The Witch Trials of J.K. Rowling—a podcast produced by another erstwhile-canceled journalist, the co-creator of The New York Times’ “The Daily” podcast, Andy Mills.

By now it should come as no surprise that Rowling, the author of Harry Potter, is most vehemently denounced by former super-fans of Harry Potter. She is simultaneously among the best-selling and most-canceled authors of her time—some of her protesters display the palimpsest of Harry Potter tattoos. The reason Rowling is denounced, to put it as delicately as possible, is because she violated a social taboo, or offended what a community, in its own words, considers “sacred.”

The archetypal scapegoat, like ‘the artist’ or magician, exists on the boundary between sacred and profane, a walking paradox —“poison and cure,” an outcast at the center of attention, the infected healer, a thing nobody wants but everyone needs. A person everyone hates to love, and loves to hate.

It’s an uncanny coincidence that the entire Harry Potter oeuvre, for which Rowling is most famous, happens to revolve around magic.

Its author was once protested not by far-left activists but fundamentalist Christians, in a “satanic panic.” The shift in protest demographics surely reflects changing ideas about what our society, or the ever-splintering factions of it, holds sacred.

If you want to determine what a society considers sacred at any given moment, look for what it deems profane. Literally: look at profanity, or curse words.

Forbidden words (or in some belief systems, like the Byzantine Church or Islam, images). The Lord’s name-in-vain. Images of the Prophet, or Savior. Holy-this and holy-that. Mother—s. Human body parts, or what comes out of them.

Profanity is the mirror image of what we deem sacred, and are proscribed from saying or portraying. The more taboo a signifier, the more sacred, or threatening to the sacred, the thing it represents is to a community.

What are our verbal taboos of late, our most offensive, or controversial, words?

Not coincidentally, many of these words that are taboo, often for good reason, represent people that are, or were recently, the recipients of social opprobrium—the “marginalized,” in today’s parlance, perfectly reflecting their status as outsiders—or “victims.” Most of our most unacceptable words are in some way considered derogatory references to these communities, and most of them concern gender and sexuality, or race and ethnicity—the ultimate markers of modern difference, or alterity.

There are as well a number of seemingly-innocuous words, such as “field” or “mothers,” that have surfaced in National Health and academic language guidelines, but the fact that these have been tangentially (mis)construed as harmful references against certain groups speaks to the power of the taboo, and our sensitivity to marginalized victims.

Something significant is afoot when people historically mistreated for their difference from the status quo, often victimized with extralegal violence, are now imitated, their identities impersonated, by members of the status quo. I’ve written about so-called “Pretendians,” or people performing Indigenous American identity; people of non-African ancestry “passing” for Afro-American (a form of imitation that historically flowed in the opposite direction, during Jim Crow, for obvious reasons); and there are a host of other examples of individuals, particularly in academia, which is preoccupied with these alter identities, mimicking what sociologists call “the Other”—different, or outsider cultures—for career advancement or cultural capital.

In other words, people of a certain mindset are self-consciously imitating, or identifying with, the symbolic “victim,” or historical scapegoat—for what appear to be selfish, but what I suspect are also personal and spiritual, reasons.

Something else significant is afoot when the positive corollary of the victim—the outsider artist, “magician” or “healer”—is in relatively short supply, at least on the national stage.

The music industry, and the arts in general, in part thanks to the pandemic and streaming technology, continue to be in a state of crisis. Traditionally, artists and performers are the individuals who transgress the boundaries between, if you like, “the sacred and the profane,” address society’s ills (folk and protest songs about Vietnam and Civil Rights, for example), and provide a temporary release from the pressures of everyday life.

The outrageous behavior of rockstars, for example, by now a widely-affected cliche, once represented a vicarious, temporary exemption from stultifying social norms, and often pointed the way from avant-garde to mainstream lifestyle (consider how many people have tattoos, or long hair, or transgress gender roles, compared to the early 1960s, for example).

In a very real sense, these performers also channel violent impulses, like scapegoating, into something (mostly) containable—look no further than the mosh pit, or Altamont (another Carnival gone wrong), or Bob Dylan blasting electric guitar to a crowd of angry folkies (prompting Pete Seeger to grab an ax), Iggy Pop taunting a sea of violent bikers, the theatrical “Rock ‘n’ Roll Suicide” of Ziggy Stardust, or The Brian Jonestown Massacre berating its own audience night after night, for examples of performers courting self-immolation—professional as well as physical—and escaping, or not, by the skin of their teeth. Not to mention artists like John Lennon, Andy Warhol, or Selena, murdered or victimized by their own fans.

With ‘shamanic,’ incendiary musical performance in shorter supply, the figure who continues to channel the scapegoating impulse most explicitly is the stand-up comedian, whose job description includes skirting the line between what is taboo and what’s permissible. As George Carlin opined:

"I think it's the duty of the comedian to find out where the line is drawn and cross it deliberately."

There’s an affective magic in the power of humor to diffuse taboo subjects like “The Seven Words You Can’t Say on Television,” probing audiences to reflect on social conventions honestly, without howling for the death of the messenger.

Or, as Oscar Wilde put it:

“If you want to tell people the truth, make them laugh, otherwise they’ll kill you.”

Wilde, like Carlin and Lenny Bruce, was arrested for his pithy observations. As well as his profane lifestyle —at which few of us today would bat an eye. He went from being the toast of Victorian society to serving hard labor and solitary confinement, “lost wife, children, fame, honour, position, wealth,” in his words, when he was scapegoated for his homosexuality, while the aristocrats he had dalliances with went free.

Richard Pryor, “the prophet of American race,” as The New Yorker called him in an August 2024 “Archival Issue” on “Comedy,” similarly transgressed taboos through laughter, including the most racially-charged profanity in 1970s America, now one of the most reclaimed words in the rap lexicon.

As I’ve written before (here), Pryor came dangerously close to actual self-immolation, when he set himself on fire imitating a Buddhist monk protesting the Vietnam war on TV, while under the influence of drugs. The comedian clinically died and came back to life, and audiences, as they instinctively do with pharmakon narratives, loved him for it.

While that’s a hard act to follow, and it’s harder to get arrested, let alone condemned to hard labor and solitary confinement for one’s humor or lifestyle in America today, you can now go to prison for posting taboo words on the internet in the U.K. (The fact that J.K. Rowling has not been arrested for violating these new laws speaks to the “artist’s exemption”: we expect such figures to break taboos, and in some sense give them a pass— one reason, perhaps, that the music industry was left relatively unscathed by #MeToo).

For discussing transgender activism in a stand-up special, Dave Chappelle was initially protested by a handful of Netflix employees calling for the cancelation of his show (for anyone doubting the pseudo-spiritual aspect to this sort of spectacle, it’s hard to dismiss certain parallels between religious morality and the Netflix protestor waving a tambourine in a Chappelle fan’s face, chanting, “Repent, motherfucker!”). The comedian was then attacked onstage, at an ensuing performance, by a protestor armed with a knife shaped like a pistol, who subsequently explained, “I identify as bisexual … and I wanted him to know what he said was triggering.” The assailant also charged Chappelle with discussing homelessness.

Around this time the comedian, a little pretentiously, and with more symbolic resonance than he probably intended, mentioned in another stand-up special that many people now consider Dave Chappelle “the GOAT”—the “Greatest of All Time,” as far as comedians in the cancel-culture era are concerned, following in the footsteps of performers like Richard Pryor.

In his acceptance speech for the 2019 Mark Twain Prize, Chappelle explained that, long before he considered a career in stand-up comedy, his mother used to tell him he was destined to be a griot—the West African term for a communal storyteller, a role akin to the pharmakeus, or healer. That he was being raised, as he says, in “a hostile environment that I had to tame,” through the art of words and performance.

Chappelle then recalled cutting his teeth in the adult atmosphere of nightclubs as a fourteen-year-old, amid the crack epidemic and gun violence, addressing social problems around the black experience, much as he does today—one of the topics that’s landed him in trouble, in his routine, asking whether it’s “punching up” or “punching down” to assess the comparative victimhood of black versus LGBTQ people. He said that he credits his art form with saving his life, through its ability to theatrically diffuse tensions onstage, granting him composure in everyday life—that, as his mother said, “Sometimes you have to be a lion, so you can be the lamb you really are.” He then declared the mayor had marked a new holiday, “Dave Chappelle Day” in Washington D.C., on which the comic invited everyone to create one happy memory for themselves or others, and Mos Def and Thundercat to play him offstage.

That, in case you missed it, is a pretty telling summary of Chappelle’s self-image: someone, like “the person in Africa who was charged with keeping the stories of the village […] so that they could tell future generations,” surrounding himself with musicians. Griot, healer, pretender, performer, with the regal mask of a lion covering the sacrificial lamb, or as the case may be, GOAT. Whom the mayor granted the keys to the city, for just one day.

As I mentioned earlier, when Jacques Derrida, following the example of Plato and Socrates, spoke of a pharmakon as both “poison and cure,” he was referring to writing.

To Greek philosophers, the written word was one step further removed from the truth, the reality it was supposed to represent, a symbol of a symbol. A chicken-scratch of the spoken word, hardly able to capture all the body language and intonation of live rhetoric, etched on a wax tablet. On the other hand, as Plato noted, at the time writing was the only curative for memory loss—as Dave Chappelle noted in his acceptance speech, “they say in Africa, when a griot dies, it’s like a library was burned down.” And even with the full expression of live performance, it’s still possible to be misunderstood, accused of misrepresenting the truth, or targeted for cancelation, because of a spoken monologue.

Perhaps it’s no coincidence that writers, as much as stand-up comedians or dangerous musicians, so often fall into the category of pharmakos—the litany of self-destructive literati is endless. And journalists, as we have seen in the beginning of this series, are so often on the front lines of cancelation for trying to capture a contested version of reality, navigating all those toxic words. Why does any journalist take the risk, given what’s happened to so many of them?

The majority of once-cancelled, or simply self-exiled, writers who find a sanctuary in independent publishing are well-intentioned enthusiasts for, as Andy Mills says, “curiosity, skepticism, grace and the transformative power of listening to people you disagree with.” They don’t have a death wish, or cancelation complex, they simply want to understand and report stories.

Their job description doesn’t sound all that different from “the person in Africa who was charged with keeping the stories of the village,” in Dave Chappelle’s telling: “Everyone would tell a griot the stories and they would remember ‘em all so that they could tell future generations.” He sounds a lot like Andy Mills, when he says, “that’s why I love my art form, cause I understand every practitioner of it, whether I agree with them or not. I know where they’re coming from, I know they wanna be heard, they got something to say, there’s something they notice, they just wanna be understood.”

The more pressing question is, why are we in this moment in the first place? Aside from the reasons alluded to earlier in this series (new technologies, new ‘religions,’ new forms of protest, pandemics, climate change, the dearth of a healthy arts scene—in short, a whole “hostile environment, that [we] have to tame”)—Hawthorne’s Scarlet Letter offers some unnerving suggestions.

The model for Hester Prynne, whom Hawthorne identified with, was Anne Hutchinson—a heretic exiled from Boston for the crime of worshipping in her own home in her own way, and inviting women, and a few men, to do so as well, outside the confines of the Congregationalist church. She was a schismatic among a group of schismatics, Protestant dissidents from the Church of England. In a society of “primitive statesmen”—where the only institutions were a church, a cemetery, and “that black flower of civilization” (a prison)—heresy, or independent thought, was a major threat to Puritan stability. Anne Hutchinson, like her fictional doppelgänger Hester Prynne, had to go.

In our time, when institutions are said to be crumbling, and society splintering into ever-smaller “tribal” identities, perhaps there’s a bit of this primitive anxiety driving our version of the witch hunt. In addition to the more mundane motivations for cancelation, power and personal gain.

Not to lend credence to alarmism, but Hawthorne published The Scarlet Letter in the decade leading up to the Civil War, and there are shrill voices drawing parallels between this conflict and the 2020s. So perhaps it’s worth considering Hawthorne’s take on America, the year he was canceled from a government job in Salem, for supporting the Democrats, and the ancestor of George H.W. Bush, Franklin Pierce.

A “fierce and bitter spirit of malice and revenge” was in the air in 1848, Hawthorne says in his autobiographical introduction to The Scarlet Letter:

There are few uglier traits of human nature than this tendency—which I now witnessed in men no worse than their neighbors—to grow cruel, merely because they possessed the power of inflicting harm. If the guillotine, as applied to office-holders, were a literal fact, instead of the most apt of metaphors, it is my sincere belief, that the active members of the victorious party were sufficiently excited to have chopped off all our heads…

On the contrary, the “victorious party” in Hawthorne’s case, soon renamed the Republican Party, was the first martyr to the “literal fact” of political execution, at the hands of someone who had more in common with Southern Democrats, John Wilkes Booth.

But despite Hawthorne’s obvious bias for “the many triumphs of my party,” he accurately registered the fear and loathing that preceded a presidential assassination, twelve years before the Civil War. He spoke metaphorically of his own political beheading, or loss of a job, in the introduction to his novel, which won him “the crown of martyrdom (though with no longer a head to wear it on).” He described the election of 1848 as a “period of hardly accomplished revolution, and still seething turmoil, in which the story shaped itself”—“the story” being The Scarlet Letter. That story registered the transition between metaphorical, and actual, political violence and human sacrifice, the murder of a humorous storyteller named Abraham Lincoln.

Happy Election Day.