A fragment of jaw bone in an urn. Crematory essences, in a tobacco tin that recalls the Folgers can from The Big Lebowski.

A death mask. A carnival mask. A plaster cast. Celebrated locks of hair. A sacred heart, cured in a funeral pyre, resting in a silk-lined box. Are these the holy relics of incorruptible saints? Items from Pharaoh’s tomb? Satanic cult props?

These are the relics of the second generation of Romantic poets, self-declared “priests” of a pop religion that took hold in the late-eighteenth and early-nineteenth century. An industrial-age mystery cult, dedicated to mad love and pagan nature. With some interesting keepsakes.

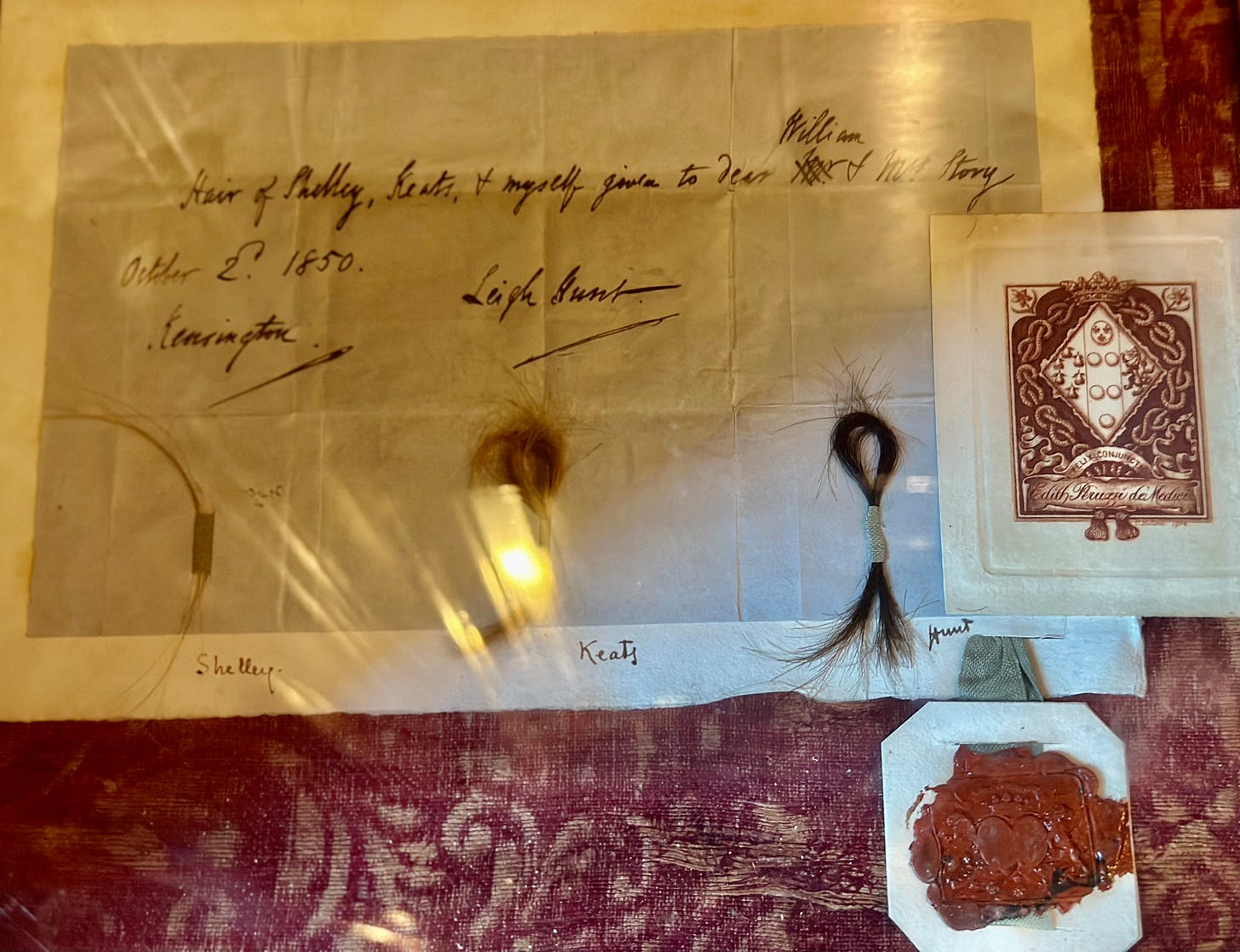

After their deaths, anything that related to Keats, Shelley and Byron was carefully preserved, first by family and friends, and later by fervent admirers: locks of hair, childhood possessions, items of furniture, books, letters, poetic manuscripts. More than just keepsakes, they were held almost as sacred religious objects.

Byronic relics ranged from the exotic (his Greek helmet, his Albanian costume, his carnival mask) to the domestic (a fragment of curtain from his marriage bed). Keats's manuscripts, including his marvellous letters, were so highly prized that they were sometimes cut into strips and distributed to friends.

Shelley's charred remains were kept by [his friend and biographer] Trelawny after his cremation and later given away piecemeal to a favoured few. Other Shelley relics, however, were jealously guarded by his family… [A] portrait of Shelley hung above precious relics: a miniature of the poet as a little boy, manuscripts and poems, reliquaries, his rattle, his guitar, and locks of hair. Kept in a silk-lined box was the most sacred object of all, Shelley's heart. The domed ceiling was decorated with stars, and a red lamp burned perpetually.

—Keats-Shelley Memorial Association

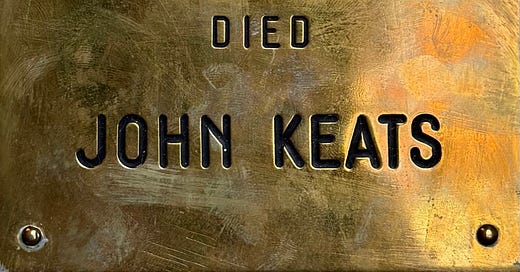

Today such relics, with the exception of Percy Shelley’s heart, are jealously guarded at the Keats-Shelley House in Rome.

I’m as hopeless as the next romantic, but like most museums (and reliquaries), this one is pezzotto - fake, artificially arranged. A stage set with artifacts from real lives. The tourist staging her own Waterhouse portrait on the terrace is perfect.

The Keats-Shelley House is pezzotto because Percy Shelley never set foot in the apartment where John Keats died, here on the Spanish Steps. And in accordance with 1820s quarantine restrictions (an Italian invention), the original contents of the rooms where Keats succumbed to tuberculosis were incinerated shortly after his death, by order of the Vatican. Of the original decor that wasn’t burned, the most notable piece is, ironically, the fireplace.

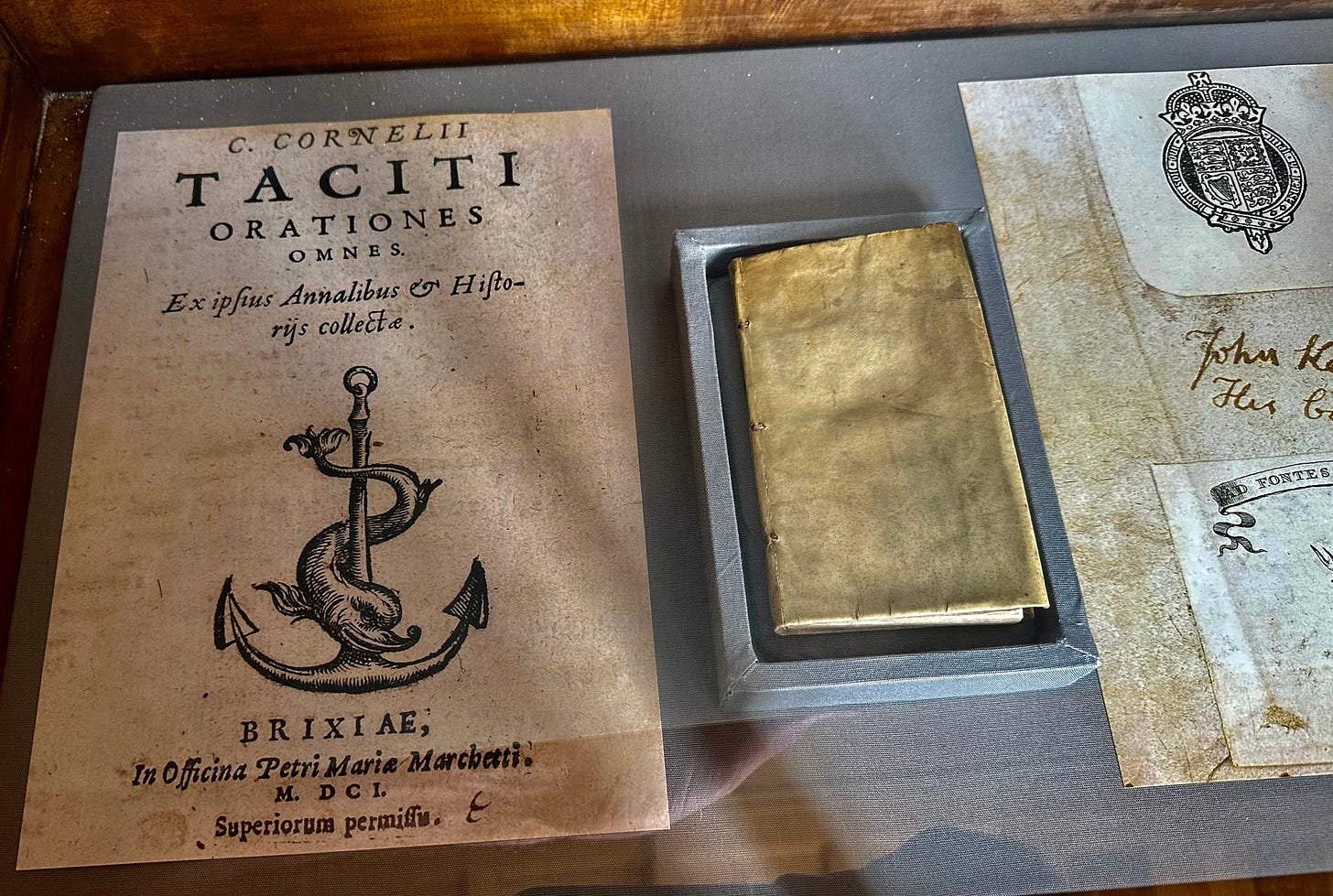

The upholstery might be new, but the artifacts and manuscripts that were brought here beginning in the early-twentieth century, with the support of the kings of England and Italy and the President of the United States, are authentic - Mary Shelley’s travel desk, signed early editions of Frankenstein, calculus equations and correspondence in Lord Byron’s hand, hand-written poems and notes by Oscar Wilde and Walt Whitman, Keats’ copy of Tacitus…

John Keats came to Italy in the fall of 1820, landed in Naples, and made his way to Rome, hoping to treat his pulmonary consumption in a warmer climate. He was dead within a few months, at age 25. A year later, Percy B. Shelley died in a shipwreck off the Ligurian coast, just shy of his thirtieth birthday, leaving behind his young wife, the author of Frankenstein, Mary Shelley. Like Lord Byron (who died dissolute in Greece, two years later at the ripe age of 36), Shelley came to Italy looking to escape infamy and bothersome English social mores, like (shades of Jerry Lee Lewis here) the incest taboo and monogamy.

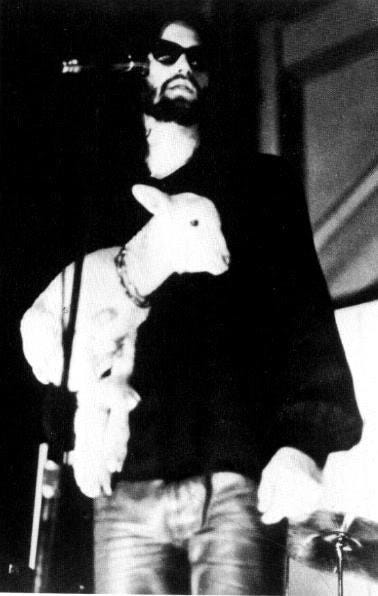

The account of Shelley’s cremation, invented by biographer Edward Trelawny (wearing sideburns and the dark cloak below) is equally pezzatto.

The Funeral of Shelley - Mary Shelley kneeling off to the left behind her husband’s colleagues (Trelawny and Leigh Hunt; closest to Shelley’s funeral pyre, Lord Byron) - a widely-circulated image of Shelley’s funeral, is a myth. Mary Shelley was never in attendance. Leigh Hunt lurked inside his carriage to avoid the stench, and Lord Byron swam into the sea, sick from smoke and gore. After ten days at sea, Shelley’s body finally washed ashore, where it was immediately covered with sand and quicklime for five weeks - Italian epidemiology again - so by the time that good-looking corpse on the funeral pyre was ready for cremation, his remains were so badly decomposed as to appear unhuman to Byron.

Parts of the legend are, apparently, true. Shelley was given a proper pagan sendoff - completely anathema at the time - his flames anointed with frankincense, wine, honey, spices and oil, some of which are in The Big Lebowski tin at the museum. The only rite missing was an incantation by a Homeric bard - a eulogy that might’ve been performed by a classicist like Shelley or Keats, had they still been alive.

A piece of Shelley’s jawbone, now in the museum, was among the few remains unconsumed by the fire. Along with his entire heart, as incredible as it seems, which may have been calcified against the extreme heat by tuberculosis (Shelley, to a lesser extent than Keats, also suffered from consumption). Trelawny claimed he grabbed the organ scorching from the flames (“In snatching this relic from the fiery furnace, my hand was severely burnt; and had any one seen me do the act I should have been put into quarantine”). Hunt preserved it in wine, before finally ceding the relic to Shelley’s widow. Mary Shelley was said to have kept her husband’s heart inside of her writing desk, wrapped in a copy of Shelley’s Adonais, for three decades, until it was removed to her own final resting place.

What sort of strange mystery cult is this, practiced by the friends and widow of England’s most infamous atheist at the time, Percy B. Shelley?

A “full-blown religious faith:”

For a self-styled atheist [expelled from Oxford for writing “The Necessity of Atheism”], Shelley was devout...

The essence of his conviction was that humanity was not enslaved to the authoritarian (and, he might have said, disciplinarian) God on which he had been raised; his preferred deity was closer to the eastern, pagan model - a life-force like the pantheist spirit Wordsworth described [in nature…]

Was Shelley another hippie guru avant la lettre, designing his own faith, drawing from a range of sources, buffet-style? Perhaps. But he was qualified for the job, having delved into everything from ancient Greek paganism to the more obscure corners of Zoroastrianism.

—John Keats and Percy Bysshe Shelley: Essential Poems

It’s the religion of the Age of Aquarius to come. A romantic cult of nature, love and death that’s as old as it is modern.

Keats seems to have intuited the trajectory of this cult, or at least provided a model for future imitators. In Hymn to Pan, he venerated the spirit of nature, as the Goat-god:

Strange minstrant of undescribed sounds…

Dread opener of the mysterious doors

Leading to universal knowledge…

—Endymion (1818)

Echoing a first-generation Romantic, William Blake:

If the doors of perception were cleansed everything would appear to man as it is, Infinite.

—The Marriage of Heaven and Hell (1790)

To his fiancee, Keats wrote

I have been astonished that Men could die Martyrs for religion – I have shudder'd at it – I shudder no more – I could be martyr'd for my Religion – Love is my religion - I could die for that - I could die for you

—Letter to Fanny Brawne (1819)

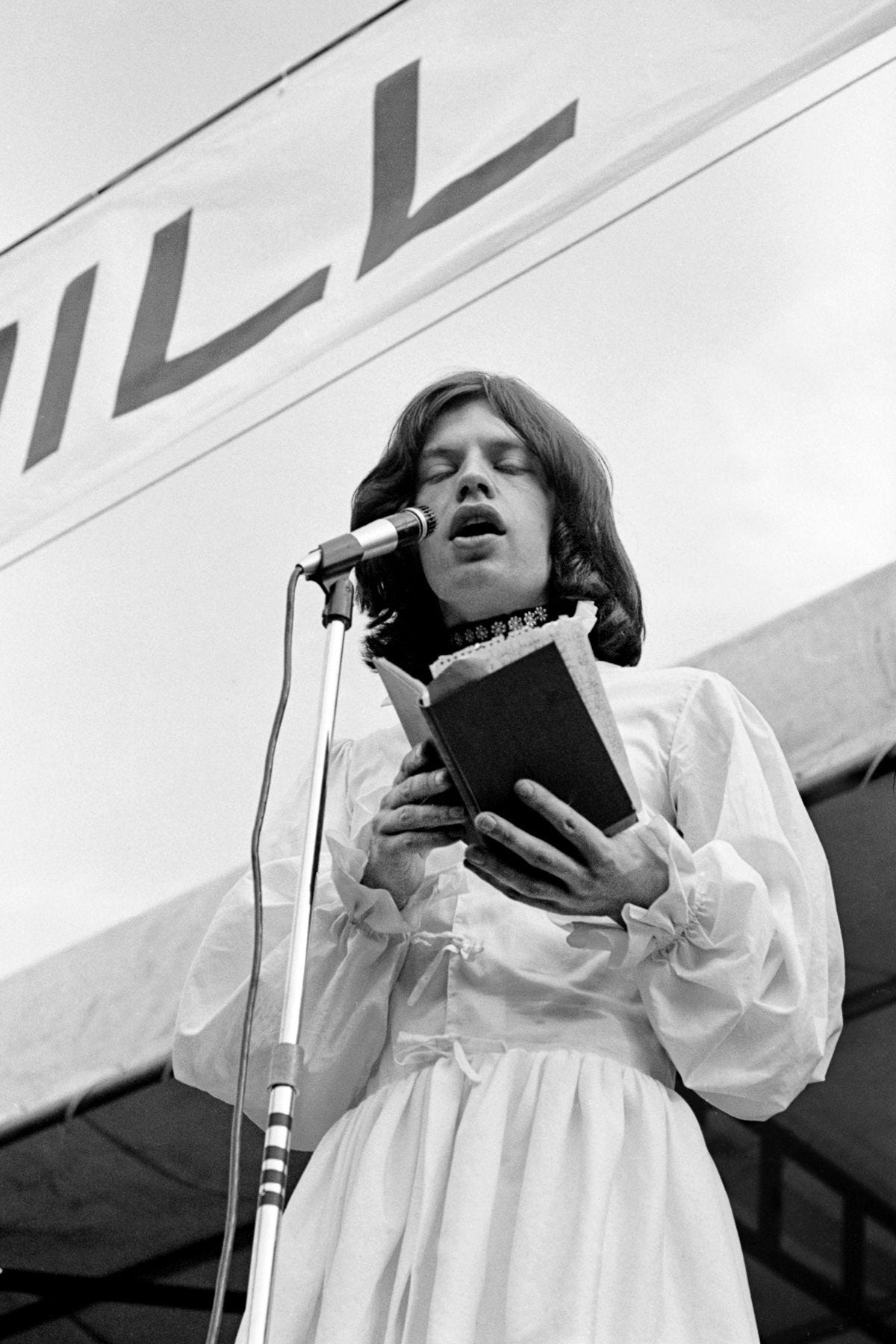

In the months between the deaths of Keats and Shelley, Shelley eulogized his friend in Adonais (the poem in which Mary Shelley allegedly wrapped his burnt heart). Years later, another long-haired radical would recite Shelley’s Adonais, this time for Brian Jones.

The title was a syncretic blend, buffet-style, “of the young Greek god 'Adonis' and 'Adonai,’ which is Hebrew for ‘Lord',” according to the Keats-Shelley Memorial Association. In Adonais, Shelley said of the Protestant Cemetery where he and Keats would be interred:

It might make one in love with death to think that one should be buried in so sweet a place.

The “holiest place in Rome,” according to Oscar Wilde, after he visited Keats’ lyrical grave on the threshold of the ancient city walls.

These - “the love of death” and “the death of love,” in the words of Leslie Fiedler, coupled with Natural Mystic spirituality - would become staples of celebrity counterculture in the West. From Keats’ and Blake’s “mysterious doors” “of perception” to Aldous Huxley’s and Jim Morrison’s; from “Love is my religion” to “Love is all you need.” They include a morbid fascination with what the Germans call liebestod (“love-death”): early mortality for the sake of romance and a beautiful corpse. All couched in polytheistic syncretism. With plenty of scandalous open relationships, unwanted pregnancies, sexual improprieties, and tragic endings. And opium.

These are now cliches, but we shouldn’t underestimate how radical Romanticism was, just because it later became a predictable model for the artistic temperament - so common we hardly notice it. Aside from counterculture fodder and artistic affectation, the Romantics cultivated nothing less than a “Copernican revolution in epistemology,” in the words of M.H. Abrams. A revolution in the way we approach perception, art, the world, and our connection to it, to this day.

The “Copernican revolution” of the Romantics was something like Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle, a century before quantum mechanics, applied to poetry instead of physics: that the mind shapes the reality it observes.

“In any period,” Abrams says in his analysis of the Romantic period, The Mirror and the Lamp (1953), “the theory of mind and the theory of art tend to be integrally related and to turn on similar analogues, explicit or submerged.” This applies to our current theories of mind, which seem to be preoccupied with artificial intelligence. In a recent MoMA installation, “Unsupervised: Machine Hallucinations,” a computer is programmed to do our art and thinking for us: creating an endless stream of ‘unique images’ in response to continuous stimuli from the internet and environment - rendering the human creator a passive spectator to the artworks of his own computer.

One might add theories of science, politics and religion to Abrams’ list; they’re always related, whether the connection is “explicit or submerged.”

Metaphysical systems in particular are intrinsically metaphorical systems… Even the traditional language of natural sciences cannot claim to be totally literal, although its key terms often are not recognized to be metaphors until, in the course of time, the general adoption of a new analogy yields perspective into the nature of the old

String theory. The Big Bang theory. These are metaphors - the universe is like a [fill in the blank] - physics reaching for for metaphysics. In the same way,

Isaac Newton’s ubiquitous God, constituting duration and space and sustaining by his presence the laws of motion and gravitation, and the World-Soul of the ancient Stoics and Platonists, are often to be found dwelling amicably together in the nature poetry of the eighteenth century.

When an old analogy fails to adequately describe our relation to the world, “Our usual recourse is, more or less deliberately, to cast about for objects which offer parallels to dimly sensed aspects of the new situation,” Abrams said, by discovering new analogies - what the media guru Marshal McLuhan called the function of the artist (and computers): pattern recognition. The new situation for Romantics was the industrial revolution.

M.H. Abrams, a literary critic writing in the 1950s, defined the analogy that dominated the theory of art and mind in the centuries leading up to the Romantic movement as others had, as: the Mirror. With few detours since Plato and Aristotle, art had mostly been defined as mimesis, "the mirror of nature” - an imitation of life. Perception was merely an impression of nature made on the mind’s eye, like Locke’s tabula rasa.

In the Romantic era, a new metaphor for art and mind eclipsed the mirror - the Lamp. The perceiving mind now projected and revealed, discovering what it had itself partly created. A very different, solipsistic outlook that focused on the subjectivity of the individual (still in full force today, for better or worse, in theory and politics, once derided as “navel gazing” in the 1960s and Tom Wolfe’s “Me Decade” in the 1970s). A worldview from the inside-out that was started, “in England by poets and critics before it manifested itself in academic philosophy.”

This, presumably, is part of what inspired Percy B. Shelley to make his grandiose claim (not unlike musicians in the 1960s) that writers could change the world and, without quite knowing what they were doing, intuit the future:

They are the priests of an unapprehended inspiration, the mirrors of gigantic shadows which futurity casts upon the present... Poets and philosophers are the unacknowledged legislators of the world.

—In Defence of Poetry (1820; pub. 1840)

In Shelley’s day, poets and philosophers had changed the world, to an extent we might not appreciate today; Shelley and his cohort would do the same. The image of the solitary Romantic genius isolated from society was still being created in the early-nineteenth century. Though Shelley and Byron were in self-declared exile in Italy, Byron, at least, was in exile on main street (Keats and Shelley would have to wait for posthumous success). Their poems, like the music of Wagner, became the Beatlemania of its day. “In Shelley’s lifetime, poetry went straight into the drawing rooms of upper middle-class homes,” Abrams says, and even political economists like John Stuart Mill weighed-in on the virtues of epic versus lyric poetry, deciding in favor of the latter - a reversal of traditional values, now favoring the lyrical emotions of the artist over the mimetic representation of heroic acts.

With the change from “the mirror” to “the lamp” as the dominant metaphor for perception and creativity, and from epic to lyric as the preferred genre of poetry, the art form most analogous with poetry changed as well. In place of painting, music became

the art frequently pointed to as having a profound affinity with poetry… As a result music was the first of the arts to be regarded as non-mimetic…

Pointing the way towards modernism, abstraction and expressionism, and influencing German philosophy in the music-oriented works of Schopenhauer and Nietzsche.

As Walter Pater, a critic from the following generation (Oscar Wilde’s) would soon declare: “All art aspires to the condition of music.”

The turn towards lyric poetry and music was part of the intellectual climate at the time, part of an interest in origins - primitivism. The beginnings of what what would become known as Literary Darwinism: the theory that language evolved from music. “It was standard procedure in Wordsworth’s day,” Abrams says, “when characterizing poetry, to refer to its conjectured origin in the passionate…rhythmical...outcries of primitive men.” Charles Darwin would come to a similar conclusion a century later, in The Descent of Man (1871). Around 1725, Giambattista Vico had conjectured that primordial language was an emotive form of poetry and song, and as early as 1704 John Dennis had claimed that “Religion at first produced poetry;” “the first poets were found at the altar,” a contemporary echoed. All of this replaced the audience as the focus of critical attention, with the poet - creator of language, prophet and priest as he or she now was.

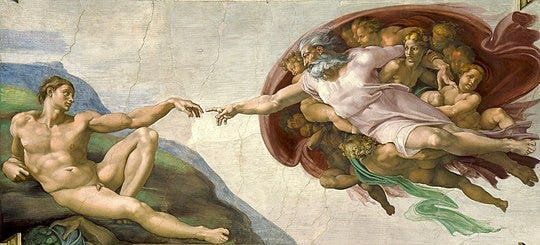

What this all boils down to is a turn towards individualism, which had been brewing for quite some time. Since the Renaissance, in fact. In the Neo-platonic aesthetic theory of sixteenth-century Italy, the artist finally graduated from lowly Roman craftsman to demiurge “Creator.” The Romantics essentially inserted something like Renaissance humanism, mixed with ecstatic spirituality, into English poetry, turning the poet into Michelangelo’s Adam, a creative genius touching fingers with God-as-nature.

In Shelley’s interpretation of Torquato Tasso, a late-Renaissance Italian who wrote not long after Michelangelo created Adam on the Sistine ceiling: Non Merita nome di creatore, se non Iddio ed il Poeta (“none merits the name of creator, except God and the Poet”).

Shelley, incidentally, conceived of his own historical moment as a modern English renaissance, or “new birth.”

The literature of England has arisen as it were from a new birth…we live among such philosophers and poets as surpass…any who have appeared since the last national struggle for civil and religious liberty.

—In Defence of Poetry

The “last national struggle for civil and religious liberty” on English soil was, arguably, the second English Civil War, which temporarily resulted in the democratic Commonwealth of England (1649 -1660), during the life of John Milton.

We may have him to thank for Shelley’s lack of modesty, and diabolical hubris.

Milton (1608 - 1674) did as much as any poet or philosopher to nurture the concept of the Romantic rebel, informed by a period of religious and political turmoil a century before the first wave of Romantics. A republican, Milton supported a form of English democracy - a parliamentary republic as opposed to an absolute monarchy ruled by an earthly deity, such as the Sun King, Louis XIV in France. He wrote in favor of the regicide of Charles I, after the king was tried and executed by the short-lived Commonwealth government of Oliver Cromwell. He was also a Puritan, that disaffected group of protestants who left the Church of England for America and later, revolution. For this, Milton was equated with his most infamous character, a figure who also seceded from a divine, absolute kingdom: Satan.

Last week, I mentioned the religious syncretism between Roman Catholicism and the literary theology of Dante Alighieri and St. Augustine. Milton’s Paradise Lost (1667) likewise informed Christian ideas about the Fall and the Garden of Eden. But it most dramatically influenced secular literature in the Romantic era to come, which, as implied, wasn’t really secular or atheist but rather composite, pantheistic - even, the church might say, ‘Satanic.’

Milton, intentionally or not, made a heroic individualist out of Satan in Paradise Lost. A century after his invention, Robert Burns, poet laureate of Scotland (author of the words we sing each New Years Eve), said: “Give me a spirit like my favorite hero, Milton’s Satan.” Another poet agreed with Milton’s contemporary John Dryden, when he said that, “the Devil is in truth the hero of Milton’s poem.” In the words of the Romantic eccentric William Blake:

The reason Milton wrote in fetters when he wrote of Angels & God, and at liberty when he wrote of Devils & Hell, is because he was a true Poet and of the Devil’s party without knowing it.

—The Marriage of Heaven and Hell

This has little to do with actual devil worship - Milton, Blake, even Shelley, revered Christ as a revolutionary figure - and more to do with political and poetic symbolism. For the great critic Samuel Johnson, someone suspicious of Cromwell’s Great Rebellion, Milton’s republicanism and defense of regicide, and his subsequent identification with the Satan of Paradise Lost, were founded on a '“desire for independence” which “felt not so much the love of liberty as repugnance to authority” - similar to the repugnance Percy Shelley, the self-styled ‘atheist,’ felt for the authority of organized religion.

Milton’s rebellious, tragic Satan became such a powerful signifier in the years after Paradise Lost that the Devil became associated with his author, with popular democracy, with the French Revolution, and Napoleon - a Romantic hero before he was considered a dictator (Beethoven dedicated Eroica to Napoleon, until he withdrew the honor when the general began to behave like an emperor). Milton’s Satan became the “Promethean hero,” hubristically stealing fire from the gods, sacrificing himself for the progress of humanity, or just himself - Goethe’s Faust, Percy Shelley’s Prometheus Unbound and Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein: Or, The Modern Prometheus.

Finally, Milton’s Satan was equated with the “Byronic hero” in the scandalous verse and real-life adventures of Lord Byron - a libertine emulated by bohemians and beatniks to come.

Because of the French Revolution and Napoleonic Wars, and lingering memories of Cromwell’s ill-fated Commonwealth (a republic, but a violent one), simply declaring one’s support of ‘democracy’ in England at this time was tantamount to espousing revolutionary ideology. To say nothing of atheism, which was also associated with the French Revolution, and amounted to sedition. To cast one’s chips in with the legacy of John Milton - a Puritan protestor opposed to the Church of England and the monarchy - was akin to being in league with the devil, from the perspective of the British status quo, who had just suffered defeat at the hands of American revolutionaries, and narrowly escaped Napoleon’s in Europe.

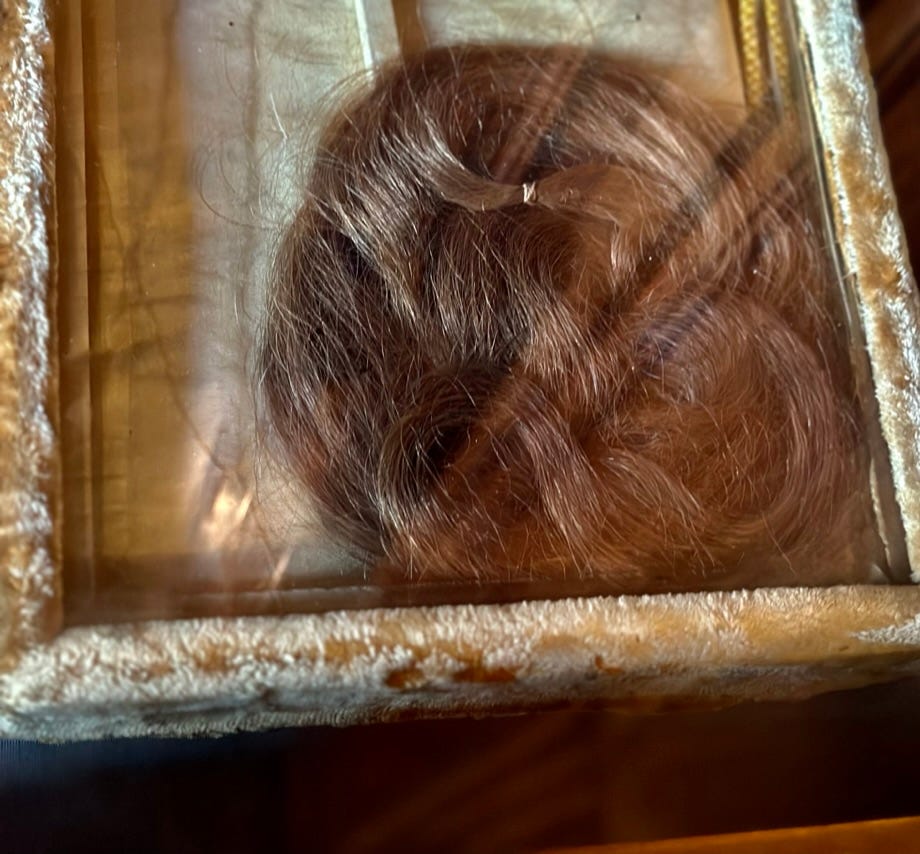

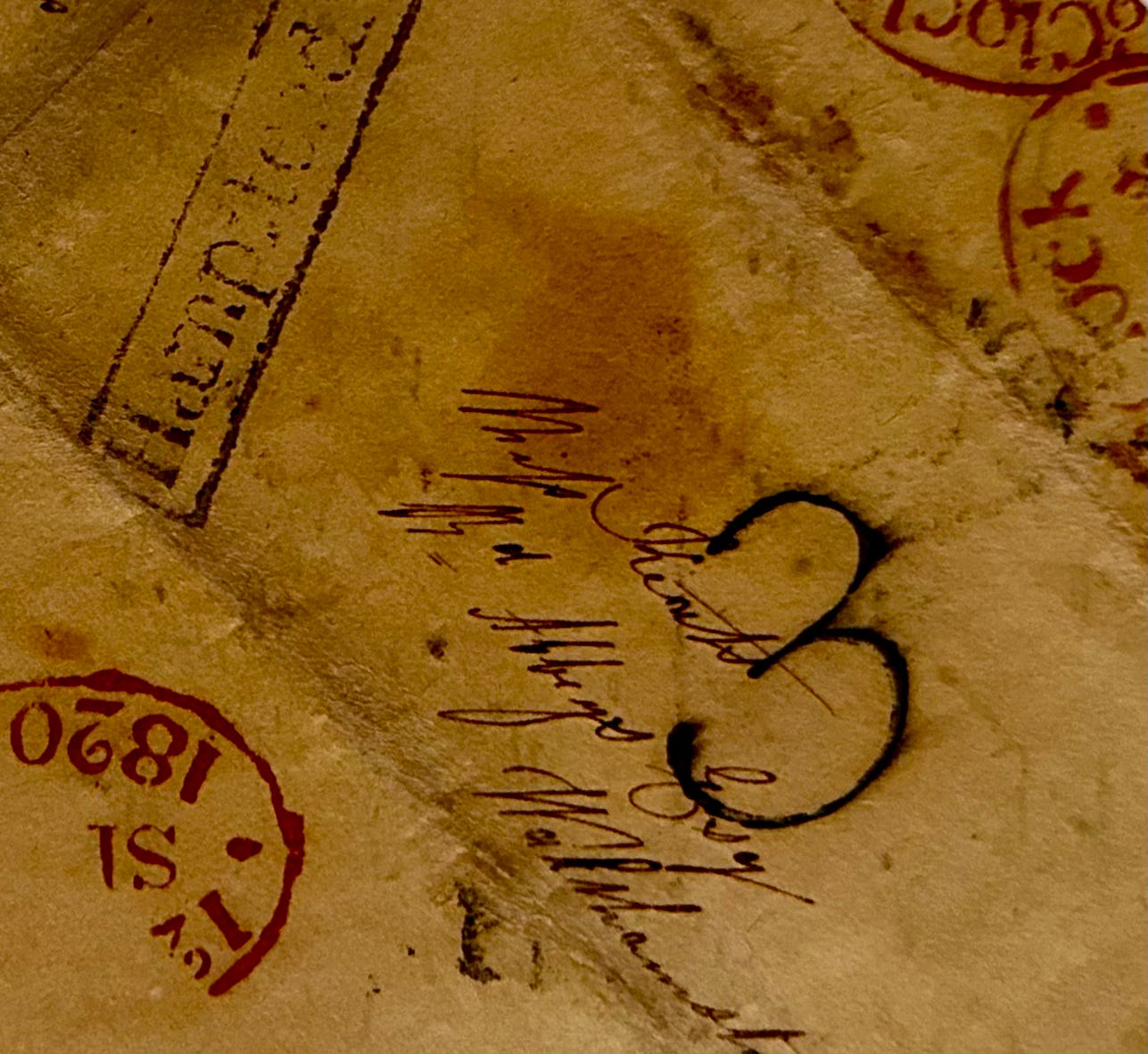

It’s not surprising then, though it was amazing, to find a lock of John Milton’s hair among the relics inside the Keats-Shelley House, in a silver scallop-shell that once belonged to Pope Pius V. The lock was safeguarded by Samuel Johnson, among other literati, in the century before it fell into the hands of Keats’ publisher Leigh Hunt. Afterwards, Keats offered “a burnt sacrifice of verse and Melody” to it (he wrote a poem), and Hunt shared a clipping of Milton’s hair with Robert Barrett Browning, which the poet combined with a lock of hair from his wife, Elizabeth Barrett Browning.

That is literary tradition, and cult fetishism. From Milton to the Romantics, the Romantics to the Rolling Stones: Sympathy for the devil - some strange religion.