While I’m attempting to tell the story of Andalusia, or southern Spain — how an admixture of influences from the East, particularly Islam and Judaism, informed the culture of Iberia, and laid the foundation for Western modern music and literature as we know it — my trip to the peninsula begins not in Andalusia, but Old Castile, to the north, in Madrid.

In a royal residence outside the capital designed by Phillip II in the sixteenth century, while he was curating his power and image as the lynchpin of a global Catholic empire, during the Siglo de Oro, or supposed Golden Age of Spain.

Phillip II’s edifice represents the antithesis of the Andalusian “ornament of the world,” as described by Maria Rosa Menocal (here) — the convivencia, or peaceful coexistence of different ethnic and religious groups. This was instead the seat of Catholic Inquisition, conquest, and empire.

Ironically, the Spanish monarchs were putting the finishing touches on this symbol of power, known as El Escorial, just as Spain was beginning to overextend itself in the New World, and failing to ‘stay in its lane’ next to an ascendent global empire, England — the seeds of the Siglo de Oro’s collapse.

But during this period of elite decadence, overreach, and Catholic nationalism, a royal reliquary betraying hints of Spain’s lost multiculturalism was compiled in this austere monument to wealth and power.

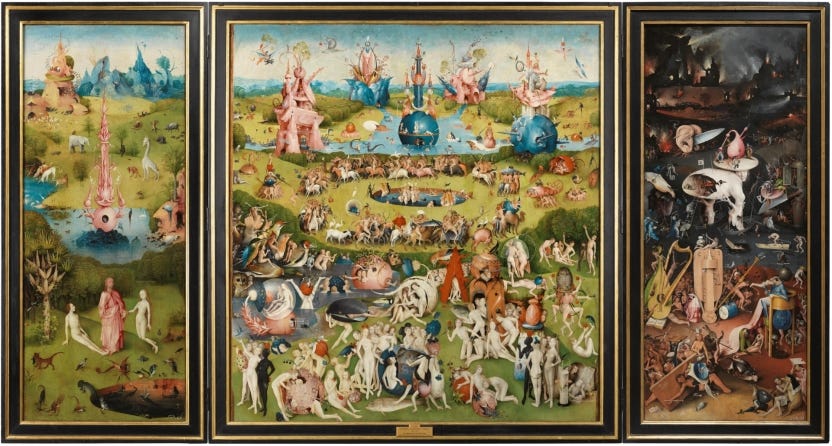

Phillip II’s collection included — along with traces of Spain’s colorful Andalusian heritage — not just the dour emblems of state power and theology, but visionary pieces of art from the empire’s territories, including the Netherlands.

Imagine, if you will, the Catholic king opening this enormous monotone cabinet inside his residence in the sixteenth century…

To reveal Hieronymus Bosch’s Garden of Earthly Delights (now housed in a more contemporary display of Spanish state treasures, at the Prado Museum).

A visual symphony of carnal pleasures, which (in my opinion) anticipates the surreal hallucinations of Salvador Dalí — four centuries before Surrealism, in the Catholic king’s collection, inside a monastery. (To appreciate the full extent of the sensual weirdness inside the king’s triptych, you can have a closer look, here.)

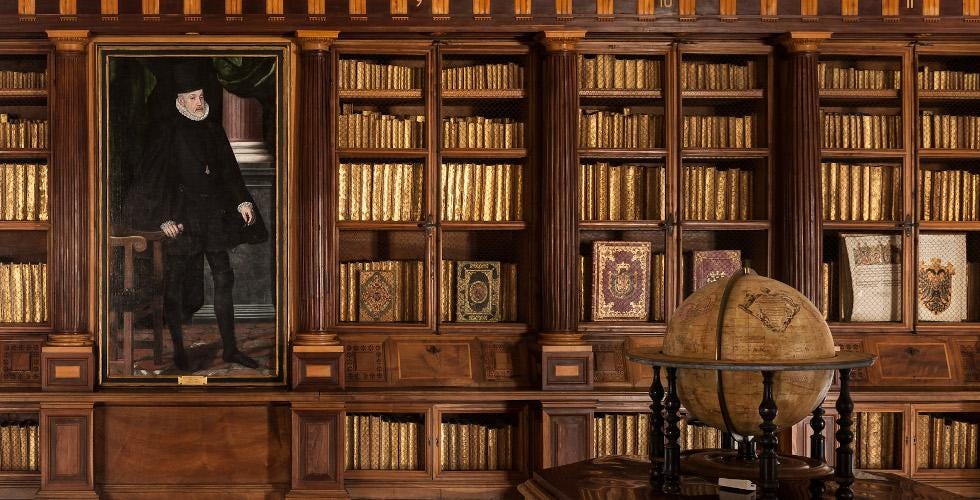

But the crown jewel in this hoard of cultural capital, for me — the reason we took two buses an hour outside of Madrid to explore this imposing monolith in the bone-chilling rain — is the Real Biblioteca.

The “Golden Library,” where the edges of every page are gilded, and the books rest upon their shelves backwards in order to reflect the sunlight streaming through the windows, lending the room an auroral hue.

Of course, on rainy days, it helps to have ceilings of vaulted gold.

There are numerous gold-leafed relics of Spain’s Andalusian heritage reproduced in the display cases here.

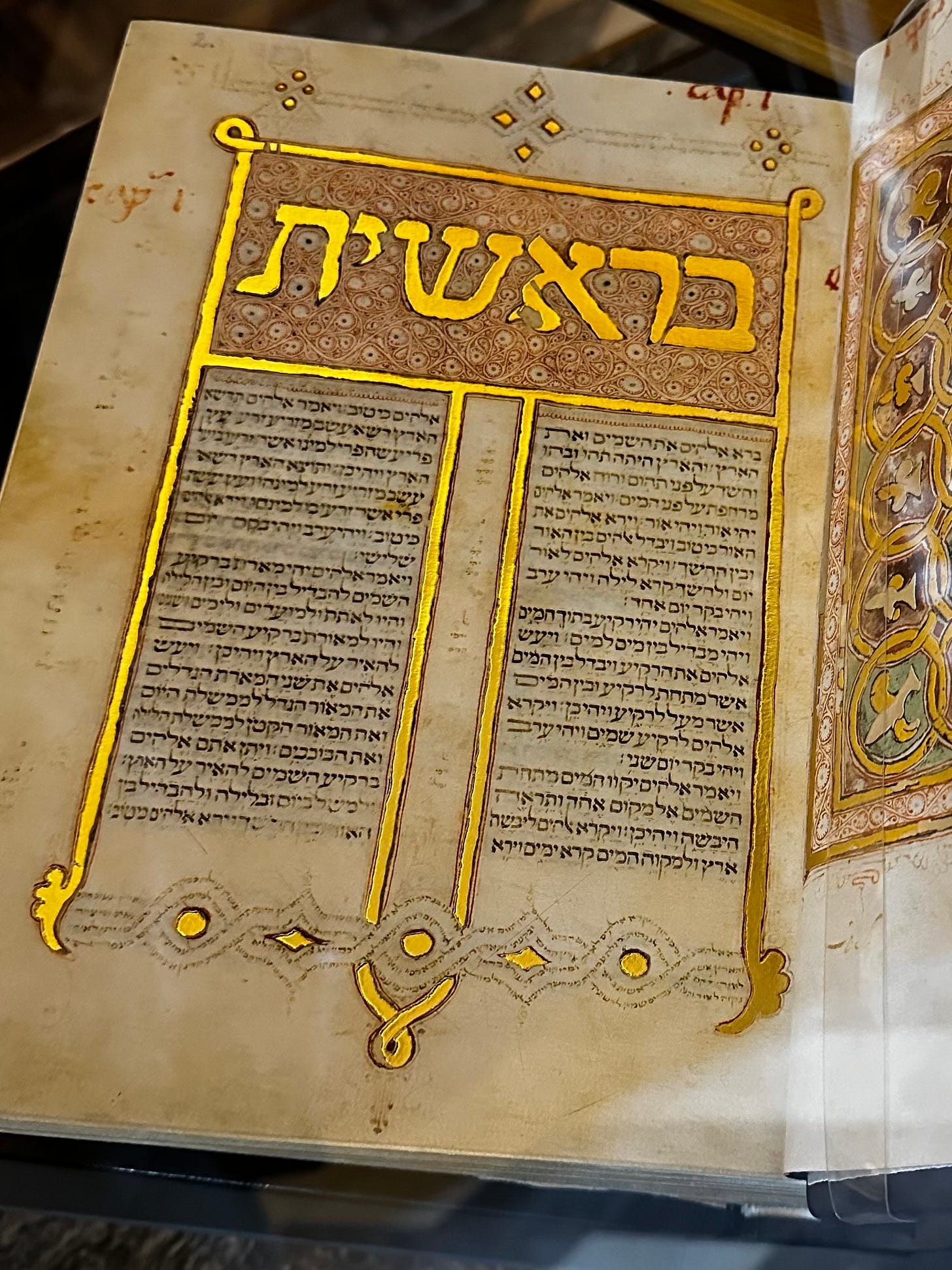

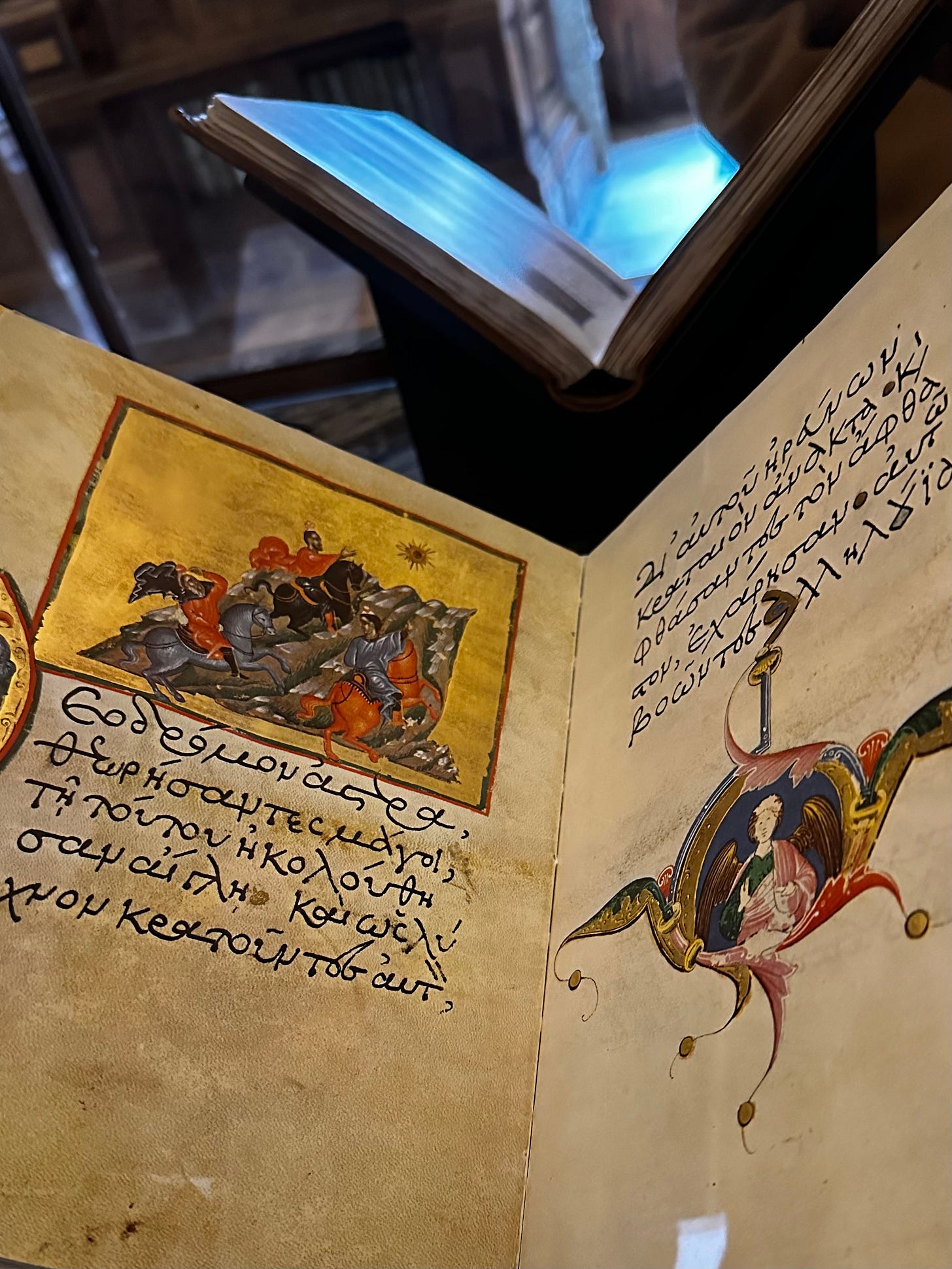

In Hebrew:

Greek:

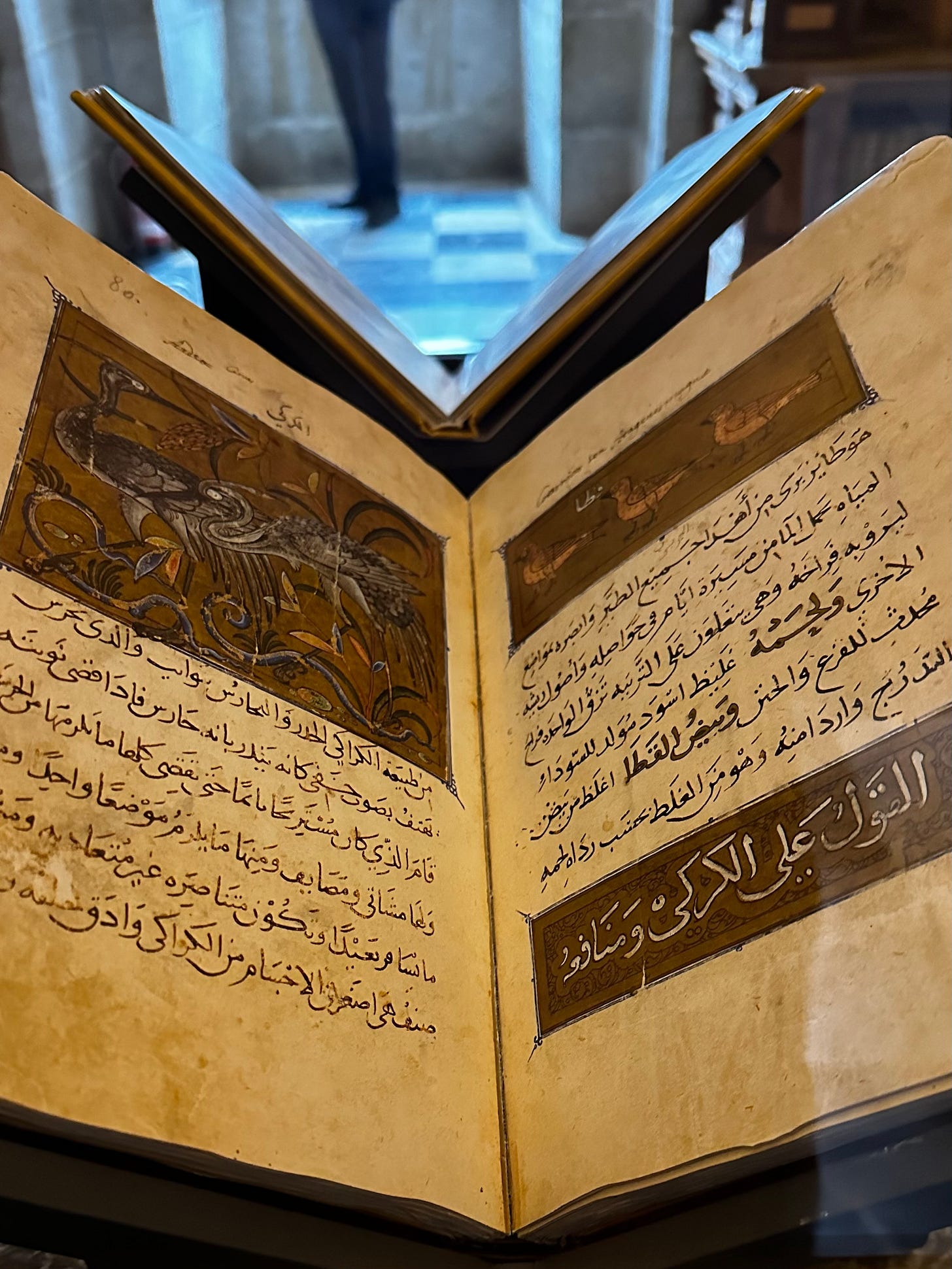

And most importantly for the purposes of this story, Arabic.

Hebrew, and Arabic especially, were the lifeblood in the transfusion of Greek classical knowledge into Europe during the so-called Dark Ages — which weren’t so dark after all, if you happened to study maths, medicine, astronomy, or philosophy in Arabia or the Near East. Especially at the epicenter of the Islamic Golden Age, in Bagdad.

The mediator in this transfer of knowledge (the “third ear” if you will), between the intellectual flowering in Bagdad and its echo in the European renaissance seven hundred years later, was Andalusia, or al-Andalus — southern Spain’s mixed culture of Muslims, Christians, and Jews.

The amalgam of these peoples and languages in Andalusia — Arabic, Hebrew, and Mozarabic (“wanna-be Arabic,” the vernacular of medieval Spanish Christians) — inspired a scribal translation process that relied heavily upon all three in order to translate ancient Greek texts from Arabic or Hebrew into Latin.

The common model was for a Jew to translate [an] Arabic text aloud into the shared romance vernacular, Castilian, whereupon a Christian would take that oral version and write it out in Latin.

— Maria Rosa Menocal, Ornament of the World

Eventually this three-tier translation process, conducted by royal scribes in the court of King Alfonso X (1221-1284), created the national language of Spain, Castilian. The lowly middleman in the translation process, the spoken romance vernacular of Alfonso’s assistants, what we now recognize as Spanish, under the king’s guidance, became the official language of the realm. Long before that, however, an admixture of these languages, pre-Castilian, percolated in the streets, in the speech and songs of ordinary people expressing, among other things, ordinary love.

But I’m getting ahead of the story. I made a pilgrimage to the royal library in search of one book in particular.

A book of songs produced by Alfonso X, El Sabio (“the Learned”) — the man who midwifed a calculated shift from Latin, as the official language of Christendom, to the romance vernacular we now call Spanish.

It’s not your typical songbook.

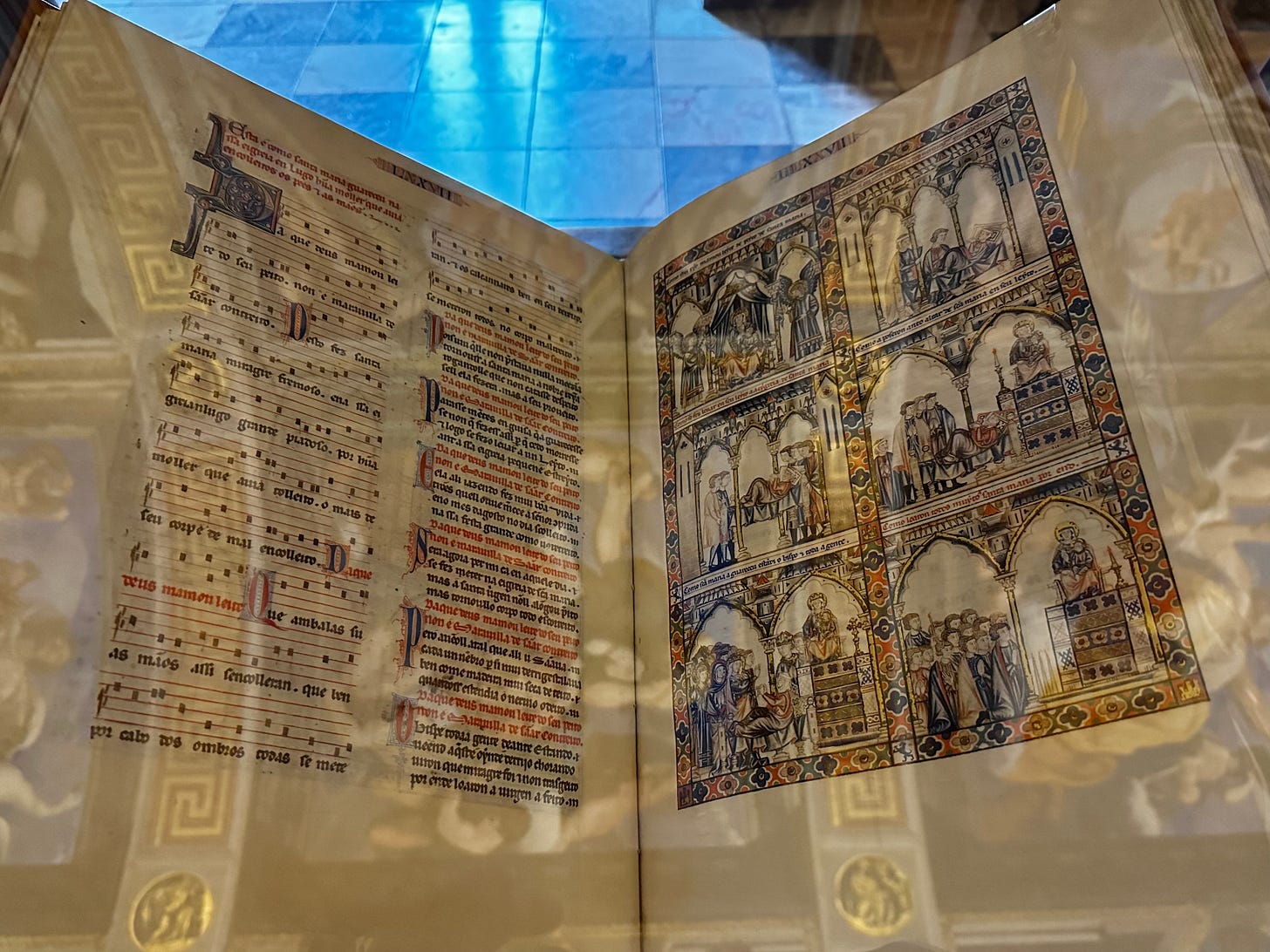

Alfonso’s manuscript, a 13th-century collection of lyrics, musical notation, and illustrations, is known as the Cantigas de Santa Maria, or Songs to the Holy Virgin.

If that sounds boring, consider musicologist Ted Gioia’s description of the Cantigas de Santa Maria, from his 2015 study, Love Songs:

“The Virgin Mary in these songs exhibits jealousy, anger, and a taste for vengeance more appropriate for a jilted lover than the mother of Christ. Even more surprising, these lyrics often describe erotic situations in vivid detail, especially in the story songs relating the miracles of the Blessed Virgin.

“Rape, prostitution, incest, the full range of sexual sins and satisfactions are held up for display.

“The illustrations that accompany these songs […] seem designed to titillate rather than edify [ …] ”

I won’t go into explicit detail (for that, readers can consult Gioia’s Love Songs), but suffice it to say that the single page of Cantiga illustrations in the display case at the Royal Library contains no nudity; the lurid scenes Gioia mentions are difficult to track down, even in the archives of the Real Biblioteca. Even — irony of ironies — on the internet. Some things, I suppose, are still sacred (no matter how profane).

There are two other Cantigas manuscripts, in Madrid and Portugal, though I don’t know to what extent they illustrate the scenes above. But however bashfully, these documents do exist, and the reluctance on behalf of the guardians of Iberian heritage to display them obscures a hidden history.

The Songs to the Holy Virgin reflect what was by the time of Alfonso X a well-established tradition: the conflation of a new cult of Catholicism from the eleventh century onwards — Mariology, or worship of the Holy Virgin, on all but equal footing with her divine male counterparts — combined with the secular love song. To put it another way, the Cantigas reflect a bizarre (from our modern perspective) mash-up of sensual and sacred passion.

The troubadours — the courtly singing poets of Southern France, obsessed with rhapsodizing the virtues of unconsummated love (mostly aimed at genteel married women) — drew on a long tradition of secular love songs imported from Spain, which were originally inspired by Arabic verse.

In Iberia, Jews and Christians were free to sing about the pleasures of carnal passion without fear of censure — as long as they sang in Arabic. Muslims, likewise, reserved the naughtiest punctuations to their songs (in Menocal’s chaste paraphrasing, something like “shut up and kiss me,” but dirtier) to be sung in non-Arabic dialects like Mozarabic, the language of Iberian Christians.

In other words, at the turn of the first millennium it was acceptable to give free rein to expressions of sensual pleasure in the language of ‘the other’. Much of this profane poetry was written by, or in the voice of, female authors, and the surviving evidence of these songs is enough to make you blush (“make my anklets touch my earrings,” is a tame example).

The cross-fertilization that this sort of encoded singing inspired is illustrated in the Cantigas, which depict Arabic bards singing alongside their European counterparts.

In the cultural exchange across the Pyrenees mountains between Spain and Southern France — whether through conquest, trade, or in some cases, human trafficking of Islamic musical entertainers and concubines called qiyan — these sensual female love songs from the south were imported and, in time, sublimated into a more socially-acceptable form of passion (from the Roman Catholic, and aristocratic perspective): the lofty verses of the troubadours, who sang in coded verses about the virtues of married noblewomen in Provence and other territories.

The troubadours derived their language of romance, almost equally, from the secular love songs of Andalusia, and the religious poetry of agape, or spiritual love for God. In particular, spiritual love for the most divine, unattainable object of all, the Virgin Mary.

Dante, Petrarch, and Bocaccio, the three poets credited with turning a vernacular romance language (in their case, Italian, as opposed to Latin), into the language of a ‘respectable’ literary tradition, all wrote verses inspired by women with whom they could never hope to consummate their passion (especially after these women died prematurely). Their actual wives and lovers, meanwhile, go unmentioned in their autobiographical verse.

In Petrarch’s case, he titled his written verses the Canzionere, or songbook, indicating the intimate link between love songs, troubadours, and the beginnings of modern Italian literature (and by extension, much of the Western canon).

The obsessions of these Italians also highlights an intimate link between what modern psychologists would call a neurosis of sexual repression and transference, and the creative impulse of these poets, who seem to have substituted love for religion, and songs for sex. (In The Divine Comedy, the highest place in paradise is reserved for the woman Dante would never embrace, Beatrice.)

The Cantigas de Santa Maria represent a curious moment in the history of ‘Western’ music and literature — which, I’ve hopefully implied, is much more ‘Eastern’ than some might think.

These songs and images were drawn from the court poets of Alfonso “The Learned” — and perhaps from the verses of the king himself, who had literary aspirations of his own — written down by scribes in the vernacular language of common people (in the the codex at El Escorial, in Portuguese and Galician), musically notated, and beautifully (sometimes disturbingly) illustrated.

They appeared almost a century after the last troubadours of Southern France were punished or expelled, along with their royal patrons — by the Catholic church in Rome, in an Inquisition against the heterodox belief system of Provence, a case of Christian-on-Christian violence known as the Albigensian Crusade — and a few decades before another troubadour fan, Dante Alighieri, penned his Divine Comedy, and rewrote the history of Catholicism, literature, and love.

The songs preserve the spiritual love language that partially inspired the conceits of the troubadours, while at the same time betraying, however awkwardly, their mixed roots in the carnal verses of Andalusian and Arabic love songs.

This 500-page manuscript, as far as I can tell, documents the moment when the cult of the Virgin Mary, the courtly love of the troubadours, the sex songs of the south, and a literary movement based on higher learning, Greek translations, and the vernacular language of the streets, collided.

Not to mention, it’s wonderfully strange — especially in the library of a king who led the Catholic Inquisition.