Note to readers: this is a quick one.

The way I see it, I offer two services at The Third Ear:

1.) Compiling articles and information from the Internet and print journalism—a series now referred to as “Bits and Pieces.”

2.) Rambling-on about books, films, music and places (also known as travel writing and criticism.)

I realize my exhaustive enthusiasm with regard to number 2 can be, well, exhausting.

I’ve begun to consider the latter version of The Third Ear as a type of note-taking. I compile all my thoughts, quotes, audio and visuals for future reference, and subject readers to, say, a seventeen-minute screed on the similarities between Bob Dylan and Ralph Ellison, in one long blow.

This is a selfish endeavor.

Some of you may find the long-reads interesting from time to time (and I will continue to write them), but the mission statement for this newsletter begins with the assumption that the subscriber’s most valuable commodity is: time. And I fear I’ve taken-up more of yours than preserved it, with every twenty-minute article.

So, I’m introducing a third format: “Taking Notes.”

I have stacks of notebooks. Notebooks I rarely reread, and piles of books thoroughly vandalized—underscored and annotated, with notes I seldom consult afterward (except on-the-fly, as I write these articles).

The earliest of these Moleskines and marginalia began as underage attempts to extract meaning from—and steal inspirational material for—stories, songs and lyrics. Hence the name, Taking Notes—most of my early notebooks have musical notation—chords and keys—jotted next to the words. And now I spend much of my time writing about music, for The Third Ear. Either way, I’m attempting to take, or Steal Like an Artist, notes and ideas about music and literature.

This is Love and Theft—pilfering what might be future shards of “lyrics,” as well as ideas for other forms of writing. It’s also an act of memory and making sense—hopefully, eventually, for the benefit of others as well as myself.

(This article, “How I Take Notes,” has helpful ideas for those of a similar bent, when it comes to remembering what you read, and using it for longterm future projects.)

Rather than subject readers to the full process of digesting a text in a single, endless attempt, “Taking Notes” will offer one quotation, summary, or insight about something I’m reading, seeing, or hearing.

Then maybe I’ll use it later, to bore you to death.

Or bring someone back to life.

Lately I’ve been reading and writing about Spain. Specifically, about how medieval lyrics and love poetry from the Hispano-Arab world influenced modern Europe, incognito.

The book I’m taking note of today is María Rosa Menocal’s Shards of Love: Exile and the Origins of the Lyric.

Menocal (rest in peace) was a respected medievalist at Yale, alongside perhaps the most famous literary critic in the world at the time, her colleague, Harold Bloom. In other words, these are nerd’s words, ‘boring stuff,’ in Shards of Love—lit. crit., for a specialized audience.

But part of Menocal’s assertion is that much of high-classic litera-chore from the Renaissance onwards comes from the gutter—from medieval love songs sung in a mixture of Arabic, Hebrew, and vulgar (vernacular) languages and rhythms. The music is mostly lost to history (without recording technology). Even after musical notation was invented by Guido of Arezzo circa 1030 CE, no one bothered to put this sonic smut to staffed paper (except in sublimated form, as songs of ‘divine love’).

But we do still have “shards” of the lyrics and history, and much of what this ‘sweet new style’ inspired is now regarded as canonical literature—but it isn’t. At least, it wasn’t born that way.

Menocal compares this, by implication, to what it would be like if we had no recording technology (other than writing), to preserve the full impact of a rock-and- roll performance—if all we had were the lyrics on a page. The essence of these ‘poems,’ of this oral tradition, would be lost, or obscured.

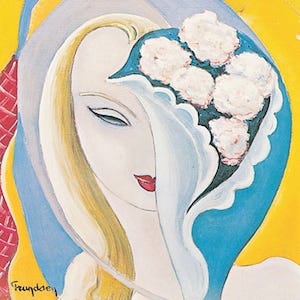

As if to symbolize this process, Menocal hides the album cover for Derek and the Dominos’ Layla and Other Assorted Love Songs on the cover of her book of high-flown literary criticism.

She compares James Douglas (“Jim”) Morrison to Petrarch (both of whom abandoned “vulgar” musical careers to write “respectable” poetry). She quotes Mike Campbell and Don Henley in-between Dante and Avicenna—in the most obscure way possible. As if everyone knows that the poets “Donald Fagen and Walter Becker” actually refer to the composers from Steely Dan—it’s like attributing the words of The Odyssey (which inspired her Steely Dan quotation) not to “Homer” but a bunch of obscure greek guys. I even caught her inserting Rolling Stones lyrics—unattributed—into a history of Romance philology, as if to prove how lowly oral tradition subtly infiltrates the ivory tower, undetected.

So it’s not merely stuffy scholarship. And neither, by implication, is her medieval subject matter, lyric love poetry, which was really music.

Anyway, I’ll delve into all that, piecemeal, later.

My “Note” this week comes from Menocal’s own notes—or footnotes. I found it buried in the final paragraph of her “Readings and Sources” material for Shards of Love.

(I’ve broken her footnote into pieces, for attention-addled screen-timers, and even included pictures, in the block quote below.)

This footnote to history has almost nothing to do with the rest of Mencocal’s book. (It has more to do with this book on musicology, Music to Raise the Dead, which it might’ve inspired.) But it’s so astonishingly “odd” that it seems Menocal couldn’t help herself.

It concerns another rock-and-roll band. The ironically-named (in this case), Grateful Dead.

Menocal:

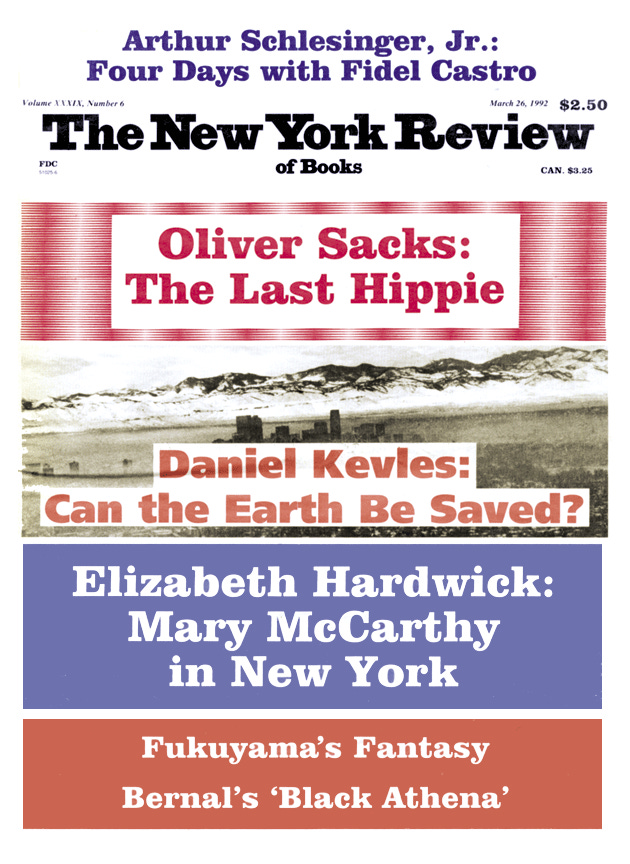

One final odd note about music and the loss of self so feared by Plato [a philosopher acutely aware, even afraid, of the power of music].

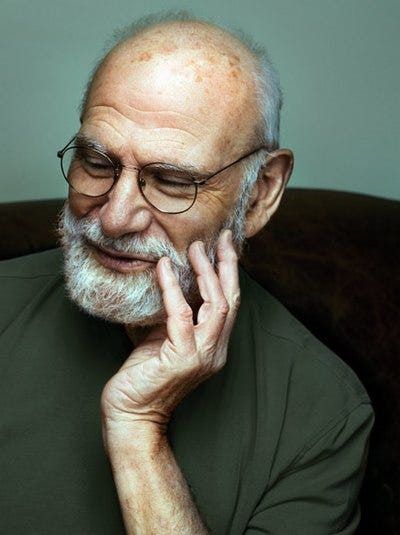

Oliver Sacks, the noted neurologist and writer, has published the remarkable story of a patient blind and gravely disabled neurologically by a huge tumor [….]. The young man had virtually no memory […] and, as if tied to memory itself, no affective consciousness, except that, eventually, it was discovered he did respond to music, and, more peculiar still, he responded astonishingly to a specific kind of music, that of the Grateful Dead.

Sacks eventually was able to make the patient come back to life, as we know it—that is, shaped by memory and affect—by making elaborate arrangements to take him to a Grateful Dead concert.

(The arrangements, as it turns out, were facilitated by Mickey Hart, the group’s percussionist, who has written a book suggestively entitled Drumming at the Edge of Magic; this is a thorough account—informed by the musicological work of Fredric Lieberman and the work on myths by Joseph Campbell, both of whom were collaborators on the project—of the relationship of percussion instruments in particular to a whole range of practices that involve degrees of loss of self: magic and shamanism.)

The multiple layers of irony are poignant when music—and the music of the Grateful Dead in particular—becomes the only stimulus that allows recovery of the self.

Sacks’s comments about the access to both memory and affect are sprinkled throughout the article, but especially in its closing paragraphs:

“With music, for whatever reasons . . . learning for Greg [the patient] is neither slow nor inefficient, but swift, automatic, and enjoyable. Moreover, music does not consist of sparse propositions (like ‘rays softened on asphalt’) but is rich with emotion, association, and meaning. Songs, quicker than anything, can evoke a character, an epoch, a world—what Thomas Mann, in The Magic Mountain, calls ‘the world behind the music’.”

—María Rosa Menocal quoting Oliver Sacks, in Shards of Love: Exile and the Origins of the Lyric (1994)

Duly noted.