In 62 AD, seventeen years before the volcanic eruption that would bury Pompeii for seventeen centuries, a major earthquake rattled the surrounding area.

Nearby, the emperor Nero was subjecting the populace to one of the many theatrical performances that made him famous, especially among fellow Hellenists and commoners, and made him infamous among the aristocracy, especially the Roman Senate. In a Neapolitan theater, according to legend, Nero ordered the spectators, who were beginning to flee, to remain seated and wait out the earthquake. So the emperor could finish his performance.

One of the most revered structures in Pompeii was toppled in the earthquake of 62.

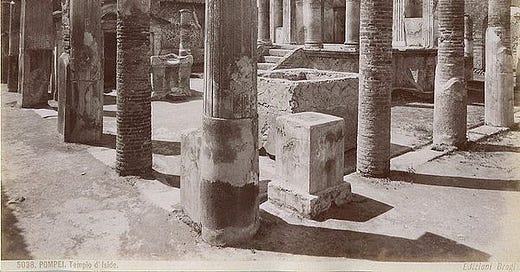

The Temple of Isis was hastily rebuilt, only to be rocked by the eruption of Mt. Vesuvius in 79 AD, preserving much of the reconstructed sanctuary, and Pompeii, through violent destruction.

Between 1764 and 1766, excavators in Pompeii made the most spectacular discovery since a well-digger discovered another site in the shadow of Mount Vesuvius, Herculaneum, far enough removed for paper manuscripts to survive the volcanic eruption.

In Herculaneum, excavators discovered the so-called Villa of the Papyri. A scholarly aristocratic retreat with rare bronze statuary, as opposed to Roman marble, in the style of ancient Greece. A pleasure palace, replete with gardens and ingenious fountain works that once bubbled through statuettes of satyrs and Sileni, through the mouths of masks and panthers, “filling the entrance to the villa with the exuberant joie de vivre of the court of Dionysos/Bacchus,” in the words of the MANN museum, where much of the Villa’s decor is housed today.

The Villa of the Papyri is so-named for its library, containing ancient (even in 79 AD) papyrus. Greek texts imported to southern Italy from the city of Pergamon in Asia Minor, most likely as a result of campaigns by the Roman general and statesman Lucullus, a close confidant of the poet Virgil.

Texts such as these, mostly containing the Greek philosophy of Epicurus, are what attracted Virgil to Naples. Today they are preserved, after a fashion, after being painstakingly unrolled by a machine invented in the twentieth century, to be read by shining a light through what remains of each charred papyrus.

The atmosphere of the gardens and fountains inside the Villa of the Papyri reflected its intended purpose, as a retreat for Roman elites looking to conduct official business in a setting of intellectual contemplation and sensual pleasure, released through the powers of wine, self-care and beauty. An elite cult of “Dionysos/Bacchus” evoking a joyful return to a state of nature, in a villa “suspended somewhere between nature and culture: the perfect setting for that imperturbable enjoyment of life that Epicurus considered to be a remedy for our everyday troubles,” per the National Museum of Naples. A place for the Roman equivalent of tech bros to macrodose wine and meditate, conducting a little business in between.

It was such a convincing mix of business, aesthetic beauty and meditative contemplation that J. Paul Getty modeled his museum in Los Angeles after the Villa of the Papyri in Herculaneum - perhaps its closest equivalent in contemporary society, after Getty’s Malibu mansion, also modeled on this idealized past.

After the excavation of Herculaneum, in Pompeii in the 1760s, excavators discovered another kind of “remedy for our everyday troubles,” one available to all castes of society: the sacred Temple of Isis.

The discovery set the modern imagination aflame, as news of the excavations spread like wildfire through the courts and academies of Europe. Pompeii quickly became an eighteenth-century tourist destination, the final stop on a modern cultural ritual known as the Grand Tour.

…Pompeii’s Isis Temple owed its success to the artists and writers involved in the Grand Tour. Between the 18th and 19th centuries, they included it on the list of “vivenda” — to borrow the expression used by Tristram Shandy — that is, the “must see” sights on the Italian leg of the tour, transforming it into one of the most evocative sites for contemporary European culture, characterized by a fusion of neoclassical ideals and romantic suggestions.

MANN, The Guide

The temple became a symbol of Orientalism, or Western fascination with the East, and the Egyptomania that swept Europe in the wake of Napoleon’s conquest of Egypt. While Isis was connected to the ancient past of Egypt in the Roman imagination, the images inside her temple - a statue of the goddess in classical Greek style, depictions of the Greek nymph Io joining her cult - connected Isis to ancient Greece. The other favorite subject of contemplation for Romans in the first century, and Europeans in the eighteenth.

Mozart visited the Temple of Isis as a child prodigy, later incorporating it as the “Temple of Wisdom” in The Magic Flute. Scores of Romantic writers and illustrators came to visit the temple in the shadow of the Theater of Pompeii, just outside the city walls, on the symbolic boundary between exotic Greek-Egypt and Italy. The Temple was immortalized in everything from French tales to Russian paintings to English novels, like The Last Days of Pompeii (1834), capturing the imagination and cultural uproar that accompanied the inception of modern archeology. The courts and collectors of Europe eagerly awaited further discoveries from the 1760s onward.

Just as Napoleon’s conquest of North Africa awakened European intrigue in all things Egyptian, the original Temple of Isis was inspired by the infusion of Egyptian culture in Rome, when Julius Caesar’s nephew Octavian (soon to become the first Roman emperor, Caesar Augustus) conquered Cleopatra and Marc Antony’s last redoubt in Alexandria in 31 AD, making Egypt a part of Rome.

The cult of Isis had entered Italy about seven centuries earlier, not far from Pompeii, with Greek colonists in Cuma. But after Rome’s conquest of Egypt in the last century BC, the cult of Isis became a craze. Evidenced by her temple, a sort of sacred theater dedicated to the Hellenized Egyptian goddess in Pompeii, where inductees were initiated into the cult.

Following the quake of 62 AD, in characteristically pragmatic fashion, the Romans repaired practical infrastructure first - transportation, plumbing, commerce, governance. With one notable exception - the sacred Temple of Isis. The temple was notably intact, compared to other structures that remained un-repaired from the earthquake, when excavations began in 1764.

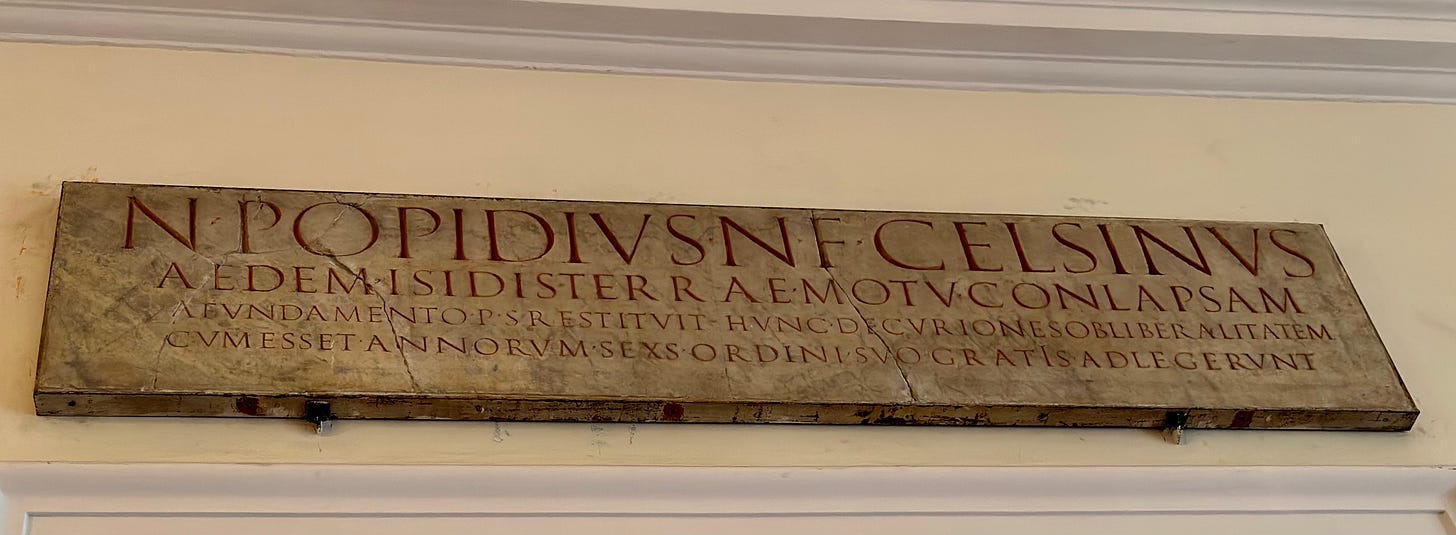

Visitors to the archeological site in the next millennium were greeted by an inscription, revealing the motivation behind the temple’s reconstruction.

After 62 AD, the dedication explains, the temple was reconstructed in honor of a six year old boy. One Numerius Popidius Celsinus, the son of a freed slave. The boy’s father quickly rebuilt the temple in his son’s name - as an investment in his future, to attach the boy’s name to the glory of Isis. It seems to have worked - the son of a slave ascended to the Senate of Pompeii.

The cult of Isis was one of many mystery cults imported to Rome from Egypt and the East, readily adopted by Romans and syncretized, or combined, with local spiritual practices. The history of the Temple of Isis, and its location on the the city boundary, in the shade of the Large Theater, is indicative of the character of mystery cults - a form of musical, religious theater, you might say. Whose artisans and practitioners came from the same social strata as theatrical performers.

The divinities revered in mystery cults like Isis’, imported from abroad, were embraced most of all by citizens excluded from the status quo - women, freedmen, and slaves. People seeking spiritual affirmation and the promise of improvement in the afterlife, outside the official temples dedicated to the gods of city and state.

The great socio-economic, cultural and existential changes resulting from the Hellenistic, and then from the Roman expansion led to the gradual diffusion in the Mediterranean of various Eastern cults (Cybele, Mithra, Sabazios). Like the cult of Isis, all of these cults featured initiatory magical rituals and involved a fanaticism sometimes verging on the orgiastic. Also present in the Vesuvian sites, they owed their success to their ability to satisfy new spiritual needs and a growing quest for individual salvation, especially among the lower-middle-class masses.

MANN, The Guide

In a time of social upheaval, such as the civil wars that accompanied Rome’s transition from Republic to Empire in the first centuries BC and AD, people who felt excluded from Rome’s power structure turned to alternative sources of spiritual meaning. In a related way, scholars and artists turned to Pompeii, and contemplation of the Temple of Isis second-hand, during the revolutions of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. (I shudder to think of some of the modern analogues of “mystery cult” worship in contemporary Europe and America.)

After Alexander the Great conquered Egypt in the 4th c. BC (and named a city after himself, Alexandria), Isis was easily absorbed into Greek worship, due to her many similarities with the Greek goddess of grain, Demeter.

When Rome annexed Egypt in the 1st c. BC, due to her popularity, worship of the goddess was encouraged by Octavian (Caesar Augustus), who was seeking to establish social cohesion and placate the masses. There was one caveat: Isis could not be worshipped within the official boundaries, or pomerium, of any Roman city. Like the individuals who first embraced her cult, Isis remained an integral, yet marginalized part of Roman society. Even as the upper classes began to patronize her temple out of political or economic interests.

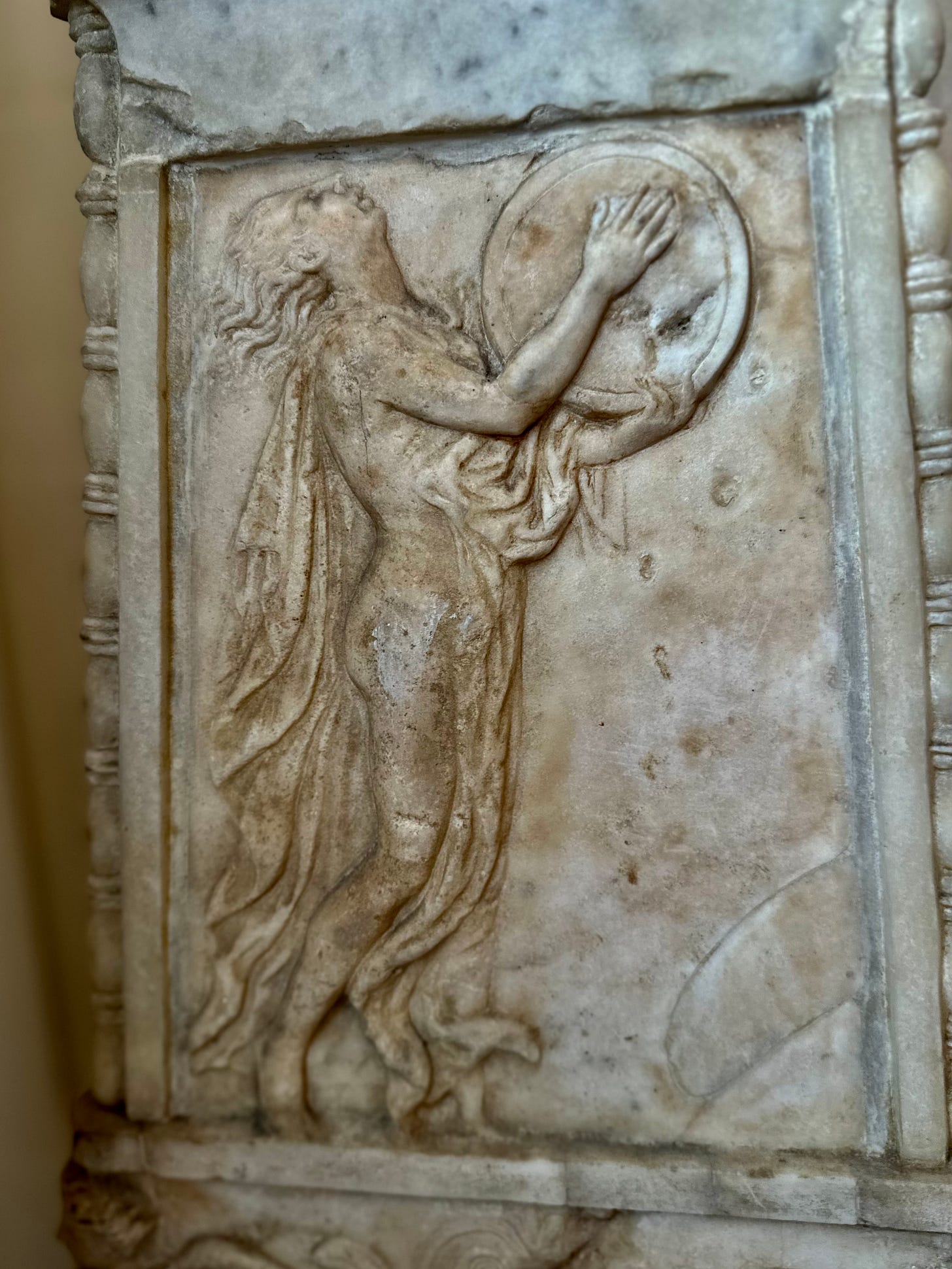

Embedded in the symbolism of mystery cults like Isis, part of their appeal to the masses, was an appeal to fertility befitting an agricultural and pastoral lifestyle, such as that of a freedman or slave, and the power of nature represented in the form of animals and, especially, the regenerative life-cycle of plants, indicative of a spiritual thirst for life after death.

Of the shortlist of cult figures mentioned above (Cybele, Mithras, Sabazios - there are many others), the first is an archetypal mother goddess. The earth-mother goes by many names besides Cybele, such as this Ephesian version of Artemis (Roman Diana). A virgin goddess of the moon, here clearly associated with maternity and fertility (foreshadowing Virgin madonnas to come).

In the Vatican, the Virgin mother is flanked by representations of Bacchus, or Greek Dionysos, revealing the persistent association, even in the modern Catholic mind, between fertility and the god of wine. Another mystery cult deity, along with Isis, one of the most widespread. Like other cult figures, Dionysus was thought to hail from the East, as far as India.

Mithra, an obscure cult deity widely revered in Rome, but derived from ancient Iran, was worshipped through the sacrifice of a bull, whose blood was a form of superstitious fertilizer. That’s about all we know of this mystery cult, other than it was ubiquitous from southern Italy to Roman Britain.

Sabazios, likely derived from a Thracian or Phrygian sky god on horseback, has been interpreted variously as a form of Roman Jupiter, Hebrew Yahweh, Greek Zeus or Dionysos. He was likely tacked-on, combined with all of the above, according to whichever deity was dominant in a particular region.

Spiritual practices have a way of fusing, or syncretizing, beneath the surface, as a society transitions from one dominant religion to another. The Pantheon, which once housed “all the gods,” the twelve Olympic deities of Rome, is now a church. Its twelve pagan vestibules are now filled with twelve Apostles. And the throne of St. Peter in his basilica was constructed using bronze taken from the Roman Pantheon.

This is religious syncretism of an official sort, hiding in plain sight in some of the most powerful buildings in the world. But a similar process takes place in the shadows, in mystery cults.

There are numerous other mystery cults which persisted in secret, whether on the edge of Athens or Pompeii in antiquity; inside the grottos of Medieval and Renaissance Naples; or, one could convincingly argue, in the Roman Catholic Church. Inside the Vatican Museum and the private collections of cardinals and popes.

Originally, the mystery artifacts above all had something to do with fertility and ecstatic communion with nature, often induced by musical trance, conducted outside the realm of state religion. Outsider gods, they appealed to outsiders in society. Before they were adopted by Roman aristocracy or modern museums.

Isis is no exception. Like Demeter or Ceres in Greece or Rome, she was associated with fertility and the rhythms of the Nile. Like Cybele or Artemis, a maternal earth goddess associated with regeneration. Like Dionysus, her myth included the physical dismemberment of a god, in this case her husband and brother Osiris. In Egyptian myths passed down through Greece, the body parts of Osiris are distributed throughout the Nile, until Isis reassembles and resurrects her husband in order to produce an heir, so she can perpetuate her divine lineage. Cleopatra found the myth of Isis expedient, equating herself with the goddess as she tried to produce an heir with Julius Caesar. The myth of Osiris and Isis has also been symbolically interpreted as the annual cycle of flooding and fertility in the Nile river basin, with the dismemberment of Osiris representing a sort of divine sacrifice.

What makes the history of Isis’ temple in Pompeii particularly interesting is that it marks a boundary, quite literally, between popular cult worship among lower-and-middle class outsiders, and the adoption of cult imagery as a display of wealth and prestige. A means of obtaining that prestige, in fact, as demonstrated by the former Roman slave whose son became a Senator, after he restored her temple in Pompeii.

One of the oldest and most discussed mystery cults, about which we still know very little, are the Eleusinian Mysteries. Plutarch, who was alive during the destruction of Pompeii, a Greek historian who became quite successful in Rome, in part by chronicling the lives of ancient Greeks and pairing them with Roman counterparts in his Parallel Lives, mentions the mysteries that occurred in the precinct of Eleusis outside of Athens. They were dedicated to Demeter and Persephone, goddesses of agriculture and spring. Plutarch, like many Athenians, may have been initiated into the Eleusinian Mysteries himself. (He also wrote a manuscript On Isis and Osiris, a Greek interpretation of much older Egyptian myths, which probably reveals more about Greco-Roman Egyptomania than it does about ancient Egyptian spirituality.)

Even in the Eleusinian Mysteries, in which most of the Athenian population may have been initiated, there seems to have been a desire to worship nature outside the bounds of the city, in secret, at night. In mythical terms, we might say, a desire to worship outside the realm of Apollo.

In Plutrach’s Lives, when a Greek city is founded, an appeal is often made to the oracle Pythias, the human representative of Apollo, god of light and order (no surprise, considering Plutarch was himself a priest of Apollo, responsible for interpreting the prophecies of Pythias in Delphi, and contributed to the maintenance of this ancient oracle in Roman times). Athens, for example, is founded after the mythical hero Theseus receives a favorable Delphic prophecy, in Plutarch’s Lives.

While Apollo, the Sun, is associated with guiding light, order, and the polis or city, the divinities central to mystery cults, worshipped outside the city, seem to be associated with another kind of light. The kind that shines in darkness.

Throughout Italy and Austria, in the Greco-Roman statuary gobbled up by the Habsburgs in the Kunst museum, by Venetian doges and princes in the Correr, by cardinals and popes in the Vatican, or by Bourbon royalty in Naples, I noticed a recurring theme as I searched for a certain decorative pattern, often referred to as “grotesque” (for reasons I’ll discuss next week).

Whenever I discovered such a pattern in the royal museums of Europe, it was most often etched into one of two types of sculpture: an enormous candle holder, or a sarcophagus. Many of these funerary ornaments and giant candlesticks portrayed figures from mystery cults.

Putting aside the “grotesque” ornamentation embroidering most of these artifacts - a decorative pattern which looks like this, a combination of human, animal, and plant forms…

… all of these items emblazoned with grotesques and mystery-cult imagery are related to death or torches. I thought this might be a curious result of elite tastes or museum curation, but it seemed to be a strangely persistent pattern. Then I saw the light.

The correlation is pretty straightforward.

The success of the cult of Isis in the Roman Mediterranean is based on a perspective of otherworldly salvation channelled through mystery rites, whose secret ancient sources are careful to maintain. The ritual of initiation into the mysteries, which had to take place at night, revolved around the archetypal symbolism of light: the discovery of numerous oil lamps in a small room [in the Temple of Isis…] has led scholars to identify this room as the sacrarium, the space used for night-time initiations.

Mystery rites took place at night; they needed light. Participant were concerned with an alternative spiritual resolution to death and mortality. Part of the appeal, even for initiates who were central to the affairs of the city during the day, was conducting these secret rites under cover of darkness, outside the city walls - the reason the god of light himself, Apollo, isn’t a part of this “archetypal symbolism of light” and lamps, which at first seems like a curious omission.

Apollo was associated with the founding of cities and the establishment of state order, and mystery cults were specifically designed to escape that order, if only for an evening. Most of the images on these lamps depict Maenads, wild women synonymous with drunken disorder and the cult of Dionysos. Why they came to adorn the expensive lampposts and frescoes of the aristocracy may be similarly straightforward: most people drink wine at night, ecstatic orgiasts and Senators alike.

The images of Maenads and Bacchic dancers below, taken from the so-called Villa of Cicero, would have appeared against an entirely black background. They seem designed to jump out at viewers by candlelight, sometime after happy hour.

Because they were associated with nocturnal mystery rites, such figures probably became decorative motifs for candleholders, and other instruments of nighttime pleasure. In the same way that the Temple of Isis was theatrical - many of the murals were inspired by the lowly art of theater design, and worship of Isis, like Dionysos, was accompanied by musical instrumentation - the homes of wealthy aristocrats like the owners of the Villa of the Papyri or the Villa of Cicero were “theatrical,” designed to induce pleasure and enjoyment, often to the accompaniment of wine and music.

I consider the cult of Isis another likely instance, à la Ted Gioia’s Subversive History of Music, where lowly outsiders determined the practices and tastes soon to be adopted and enjoyed by the status quo. That is, until the status quo began to feel threatened by theses subversive cults and banned or persecuted them, as the cult of Dionysos was eventually banned in Rome, and another obscure Eastern sect known as Christianity was persecuted around the same time.

Most of us know the end of that story in Rome, and who came out on top.

What’s remarkable about the Temple of Isis, and a few other buildings owned by former slaves in Pompeii, such as the Villa of the Mysteries - is that a freedman was able to stake his claim to this history, which has only been preserved because of a volcanic eruption. The paradox of Pompeii itself, the city immortalized through destruction, radiates a cult mysticism of its own, an integral part of the city’s mythical appeal in the centuries since its rediscovery.

Pompeii owes its myth to the violent and immediate destruction of living beings and things, to the terrible imprints of its celebrated casts, to the final moments of its places of pleasure. It is a myth of love and death, romantic and decadent, that is still capable of capturing our collective imaginations with the sublime horror of an immortal disaster.

And yet, the museum goes on to say, in the first half of the 1700s it was not Pompeii but Herculaneum that was on the lips of collectors and scholars, the treasures of an aristocratic retreat known as the Villa of the Papyri. That changed with the excavation of a mystery cult, whose temple only existed thanks to the efforts of a freed slave who rebuilt it and dedicated the honor to his son, making him a Senator in the process, and setting the elite cultural trends of Europe seventeen centuries after his death.

Next week, I’ll look at how someone born into the upper echelons of Roman society, none other than the Emperor himself, altered the cultural history of Europe by aligning himself with a profession occupied by servants and slaves: the lowly - one might say “grotesque” - role of “the artist.”