"The Endless and Noisy Chorus"

Outstanding journalism from a Frenchman in Walt Whitman's America

Meet Me in the Bathroom - the documentary film adapted from Lizzy Goodman’s superior oral-history, Rebirth and Rock and Roll in New York City 2001-2011 (which I wrote about last week in the context of 9/11) - is bookended by voiceover incantations from Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass. The section “Give Me the Splendid Silent Sun” (in which Whitman decides keep your Sun, give me New York City), is an ode to Manhattan. As a whole, Leaves of Grass is an ode to America - “America” is the opening word in the preface to the first edition, which argues that “The United States themselves are essentially the greatest poem.”

Always transforming to the rhythms of history, half at odds with itself, continually re-citing itself through her constituent parts: the American people - who “of all nations at any time upon the earth have probably the fullest poetical nature,” according to Whitman.

As American writer Paul Berman indicates, by poetry, “Whitman meant something more and other than meter and rhyme. He meant something akin to religion and ethics,” a guide to self-definition. “He meant that by following those prescriptions you yourself can become a work of art,” a work of self-determination.

Typical American individualism.

The incantation in Southern and Lovelace’s film about the early-aughts in New YorkCity - a time and place, as Karen O of Yeah Yeah Yeahs says in the film, to “reinvent yourself” - omits the Civil War imagery Whitman later added to his magnum opus, as he edited Leaves of Grass in the years after the first edition (too bad - in the film, Whitman’s martial imagery might have resonated with the drumbeat of wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, or “the sight of the wounded” after the September 11th attacks):

People, endless, streaming, with strong voices, passions, pageants,

Manhattan streets with their powerful throbs, with beating drums

as now,The endless and noisy chorus, the rustle and clank of muskets,

(even the sight of the wounded,)Manhattan crowds, with their turbulent musical chorus!

Manhattan faces and eyes forever for me.

The first edition of Leaves of Grass was printed in Brooklyn in 1855, in a three story redbrick on the corner of Cranberry and Fulton, on the edge of Brooklyn Heights. The Rome brothers, publisher friends of Whitman’s, owned a printing press where he set several pages of type for the first edition. The Rome brothers’ building stood until 1961, when it finally succumbed to the 1960s equivalent of gentrification - “urban renewal.” The real estate economics that reshaped Williamsburg in the 2010s, demolished Whitman’s printing house (by then a restaurant) in 1961.

I learned this when I went looking for the words that open and close the film version of Meet Me in the Bathroom, suspecting they were Whitman’s, and discovered the history of two campaigns to preserve Walt Whitman’s architectural legacy in Brooklyn. The 1961 campaign to save the building where Leaves of Grass was first printed, failed. The second campaign, to save another building, the Brooklyn apartment where Whitman lived while he finished composing Leaves of Grass, was embroiled in political controversy as late as 2019.

To quote a 1995 New Yorker piece about the first preservation effort (as the author humorously puts it) - names both “great (Arthur Miller, Marianne Moore) and small (e. e. cummings)” lent their support to the campaign. Jacklyn Kennedy got involved, along with a hundred college students. But the effort was ultimately a well-intentioned failure, led by one man whose name caught my eye - Elias Wilentz. The “proprietor of Greenwich Village’s Eighth Street Bookshop, defunct now but in its day a popular place among writers.”

Though I never saw it, I always picture the 8th Street Bookshop as a harmless version of the pornography store in Joseph Conrad’s The Secret Agent (1907) - a business patronized by Beatniks and folk revivalists instead of Conrad’s sinister anarcho-terrorists. Hawking less-prurient strains of literary contraband (W.H. Auden, perhaps, or the poetry and pamphlets of the New Left). In a small apartment above the 8th Street Bookshop in Greenwich Village, for the first time, Bob Dylan met Allen Ginsberg in 1963.

The apartment belonged to the uncle of Sean Wilentz, a young man in 1961 - the year his father Elias tried to save the remnants of Whitman’s printing house on Cranberry Street. It was also the year that Bob Dylan arrived in the East Village, soon to perform at “the Carnegie Hall” of MacDougal Street - the Gaslight Cafe, on the same bill as Bill Cosby and Woody Allen.

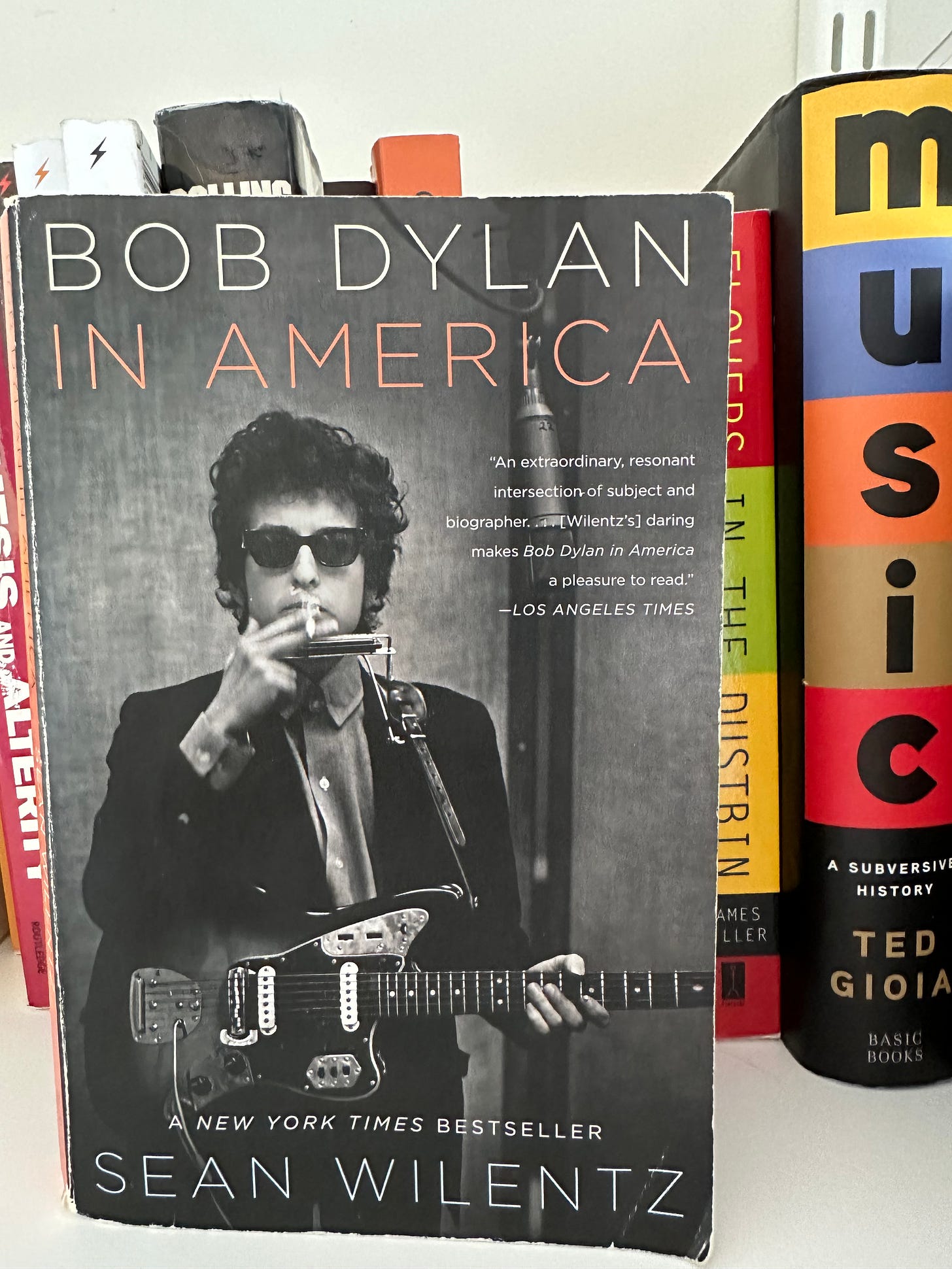

Sean Wilentz grew up in his father’s 8th Street Bookshop, and trailed him around the East Side in the early-sixties visiting the Folklore Center and other Village haunts, an experience that eventually informed the younger Wilentz’s seminal history, Bob Dylan in America (2010) - published at the tail end of the era chronicled in Lizzy Goodman’s Rock and Roll in New York 2001-2011.

I suppose it should come as no surprise to revisit Wilentz’s book and discover that the epigraph belongs to Walt Whitman - “Only a few hints—a few diffused, faint clues and indirections,” to the popular history of America. As a piece of so-called Dylanology (which so often amounts to encyclopedic fanaticism), Wilentz’s book is instead a piercing cultural history concerned with, as the title suggests, Dylan in America, “an artist who is deeply attuned to American history as well as American culture, and to the connections between the past and present.”

For Wilentz’s part, says one of America’s finest novelists, Philip Roth: “All the American connections that Wilentz draws to explain the appearance of Dylan’s music are fascinating, particularly at the outset the connection to Aaron Copeland,” and the socialist composer’s connections to the Popular Front.

According to Wilentz, Bob Dylan in America began life as an essay about Dylan’s Love and Theft - an album that was “a kind of minstrel show, in which Dylan had assembled bits and pieces of older American music and literature […] and recombined them in his own way.” (Love and Theft was released on September 11, 2001.)

Wilentz’s reflections on Love and Theft, which inaugurate the first chapter of Dylan in America, soon led to reflections on his father’s bookshop, and MacDougal Street circa 1961 - “Bob Dylan’s Yale College and his Harvard.” As Wilentz describes in the introduction:

The neighborhood had a distinguished bohemian pedigree. A century before, over on the corner of Bleecker and Broadway, Walt Whitman loafed in a beer cellar called Pfaff’s […] A little earlier, a few blocks up MacDougal in a long-gone house on Waverly Place, Anne Charlotte Lynch ran a literary salon that hosted Herman Melville and Margaret Fuller, and where a neighbor, Edgar Allan Poe, first read to an audience his poem “The Raven.” Eugene O’Neill, Edna St. Vincent Millay, e.e. cummings […], among others, were twentieth-century habitues of MacDougal Street.

A musical-literary continuity is established, the “endless and noisy chorus” of Whitman’s “Manhattan faces and eyes forever,” from Whitman and his contemporaries to twentieth-century names ‘great … and small’ (e.e. cummings, Arthur Miller... Martin Scorsese) who would try to preserve Whitman’s legacy in the boroughs of Manhattan and Brooklyn.

Those names include Sean Wilentz.

While his father Elias had tried, and failed, to preserve the printing house on Cranberry Street in 1961, a popular misconception emerged that the Rome brothers’ printing house was where Whitman actually lived. Elias knew otherwise. When his first preservation campaign failed, the elder Wilentz began perusing archival records on a hunch, assisted by a 1955 Whitman biography, looking for the house where Whitman actually wrote and slept. Paul Berman’s 1995 New Yorker article, “Revisiting the Streets that Spawned Walt Whitman’s Masterpiece,” describes that ghost hunt, as Berman accompanies the father-son Wilentz team on their search for Walt Whitman’s Brooklyn home. The trio eventually discovered the house on Ryerson Street, where Whitman once received transcendentalist visitors (an indifferent Henry David Thoreau, and an enthusiastic Ralph Waldo Emerson) while he completed Leaves of Grass in 1855.

Between 1995 and 2019, the second campaign took place to preserve the architecture of Walt Whitman in Brooklyn, with its own list of great names - Martin Scorsese (who along with Philip Roth blurbed his praises of Bob Dylan in America in 2010), and Robert Pinksy - lending their support. On the opposing side: the owners of the building for several generations. A black family trust harassed by literary pilgrims snooping around their property, and bothered by one item of revisionist history - the complaint that the populist, egalitarian Walt Whitman, now reevaluated in the twenty-first century, was actually a racist who once referred to African Americans as “baboons.” (He did, and Whitman’s racism, to the extent it exists, was typical of white Northerners at the time.)

Scholars have debated Whitman’s self-contradictory statements regarding slavery and the humanity of black Americans - he celebrated the latter in Leaves of Grass - but what seems undeniable is the degree to which Whitman was characteristically at odds with himself over the issue. In Whitman’s words, now refrained on Bob Dylan’s Rough and Rowdy Ways (2020), like the America in Leaves of Grass, “I contain multitudes.” Here we arrive at the interior of Whitman’s “greatest poem” - America, our struggle for self-definition among our constituent parts - embodied in Whitman himself. (You can read about the 2019 debate over whether to landmark Whitman’s home here, in the New York Times - “It’s Complicated.”)

In many ways, the argument over Whitman’s legacy in 2019 mirrors another historicist debate Sean Wilentz became involved with around the same time, concerning the New York Times Magazine’s 1619 Project. The 1619 Project proposed that the arrival of the first African slaves to the colony of Jamestown in 1619 marks the founding event in the history of the United States. (It’s worth noting, as Skip Gates does, that the first African in America, a freeman, landed a century before 1619 and fought alongside three conquistadors; the first African slave, to my knowledge, was shipwrecked alongside Cabeza de Vaca around the same time.)

The 1619 Project was a widely-read commercial success for the Times, especially in the wake of George Floyd’s murder in 2020. Before the summer of 2020, however, The 1619 Project had begun to fall under critical scrutiny - scrutiny which the national zeitgeist in the summer of 2020, including the firing of a Times editor and an uproar at the newspaper over racial justice, helped eclipse.

The first group of historians to question the accuracy of The 1619 Project, a trio from a “digital Trotskyite rag” known as the World Socialist Web Site, were easy enough for the Times to ignore. The next wave of rebuttals to the Project, however, included prominent historians such as James McPherson, Gordon Wood, and Sean Wilentz. In an open letter, they applauded the Project’s commitment to centering the legacy of slavery in American history, but took issue with three of The 1619 Project’s assertions. Namely, that: the American Revolution was fought over slavery; Abraham Lincoln remained staunchly opposed to racial equality throughout his life; African Americans have fought for equality with little to no support from white contemporaries. These are all factual inaccuracies, according to the historians in the rebuttal, as opposed to matters of historical interpretation. The Times responded by printing its own, much longer, editorial riposte beneath the letter of rebuttal, arguing for the Project’s validity, while quietly amending some of its erroneous assertions without issuing formal retractions or acknowledging corrections.

The rebuttals against the Times - which were not directed at the ethos of the Project itself but specific statements of historical inaccuracy, issued by a group of Socialists and the son of a New Left bookstore owner - have been conflated with another, reactionary complainant against The 1619 Project. The so-called 1776 Commission, which adheres to its own dubious interpretation of American history and aims to downplay the existence of slavery altogether, exalted by predictable opponents like Donald J. Trump. Enter again the great poem of American self-definition, in our conflicted mass of racial feelings, reduced to two numbers: 1619 and 1776.

A year ago, a French journalist made sense of this contested narrative of ourselves, by profiling an American journalist - Nikole Hanna-Jones, the author of The 1619 Project. “The Making of Nikole Hannah-Jones” by Marc Weitzmann, a Frenchman of Jewish extraction, may be one of the strongest pieces of journalism about 2020s America to emerge from our last trip around the sun.

Sometimes, like Alexis de Tocqueville in Walt Whitman’s century, it takes a Frenchman to accurately describe the lunacy of American democracy to Americans:

Who was I, a visitor from abroad, a Frenchman, neither a resident nor a citizen of the United States—what did I know of the brutality of the reactionary backlashes that do in fact disgrace American history? What did I know about living in this intemperate and volcanic country, which can seemingly go from the best to the worst version of itself almost overnight?

I doubt whether Nikole Hannah-Jones, or the historical debate over The 1619 Project (beyond the noise of the 1776 Commission) would be a blip on my radar - if not for Bob Dylan, if not for Sean Wilentz. Being familiar with Wilentz’s New Left pedigree inured me to some of the blanket accusations against the supposedly uniform “racist” and “rightwing” critics of The 1619 Project. Some of the most vehement accusations came from the 1619 creator herself, on Twitter. Yet rather than stooping into the weeds of Nikole Hannah-Jones’ more obnoxious statements - as Ida “Bae” Wells on Twitter (a twist on the antilynching heroine, Ida B. Wells), as the self-proclaimed “Beyoncé of journalism” - Weitzmann instead draws a sympathetic portrait of a journalist whose self-mythologizing bluster

mainly serves to obscure her more complex and sometimes tragic upbringing as a bright, aspirational, biracial girl from a broken town that history left behind. While her detractors are quick to point out her privilege and success as an adult, it seemed to me that America never really gave Nikole Hannah the chance to have any identity other than the one she’s locked into now

… Walt Whitman’s ethic of self-creation notwithstanding. Apart from Nikole Hannah-Jones, Weitzmann turns the lamp on America itself:

I became less interested in finding out how exactly The 1619 Project came to be or in unearthing the gossipy details of Hannah-Jones’ role at The New York Times—a tired story, in large part, of digital-age news media business-model implosion—than in how Americans increasingly find themselves in this odd and idiosyncratic predicament: splitting into opposing camps that are more or less aware of their deliberate deviations from the truth, yet clinging desperately to ever more extreme and factional positions of unreality. To a foreign observer, at least, few things seem more distinctly American than this racially tainted, self-destructive double nature of every norm, institution, and subculture.

And what could better embody these internal American contradictions than the story of the author of The 1619 Project herself—the tirelessly careerist daughter of a civil rights-activist white mother and a troubled Black father.

That story is a long one - Weitzmann traces the history of the labor movement and Great Migration in Nikole Hannah-Jones’ Iowa hometown, her maternal great-grandparents’ tradition of Czech Catholic utopianism and Republican anti-slavery - and paradoxically, their racism - it’s a long read, but the only fair and probing depiction of one of America’s most prominent, and controversial, journalists moonlighting as a revisionist historian. Particularly interesting are the figures who informed Hannah-Jones’ thinking from an early age - some of whom are quite ludicrous.

Then again, so is the popular history of America.

There’s Maulana Karenga, who created the black nationalist US (“United Slaves”) Organization in response to the Watts riots in 1965, and the Pan-African holiday Kwanzaa in 1966 - cooperating with the FBI’s COINTELPRO program (and possibly Governor Ronald Reagan) to gain supremacy over the Black Panthers. There’s Symbionese Liberation Army leader Donald Defreeze (also rumored to have cooperated with the Feds before the Patty Hearst kidnapping). The antisemitism surrounding some of these figures. And most influential for Hannah-Jones, Lerone Bennett Jr., whose 1962 book Before the Mayflower: A History of the Negro in America 1619-1962 planted the seeds of Hannah-Jones’ 1619 Project. Ever since a history teacher shared pieces of Bennett Jr.’s underground history of the United States with her high school classroom.

A taste of Lerone Bennett Jr.:

“racial cleansing, became, 72 years before the Third Reich … the cornerstone of President Lincoln’s policy.”

Most ludicrous of all, however, is the racial classification system that “never really gave Nikole Hannah the chance to have any identity other than the one she’s locked into now.” Namely, the one-drop rule. While Hannah-Jones’ white mother was the Civil Rights activist in the family, and her black father, a military veteran, was the one to raise the American flag in their front yard, it was her father’s racial identity she was thrust into as a student, and retained as an activist journalist.

As a Frenchman, Weitzmann uses the time-honored technique of using the perspective of black, or biracial Americans living in France, in the tradition of James Baldwin or post-WWI modernists, for insight into American history and customs (in addition to interviewing Hannah-Jones herself). The American expats Weitzmann reached out to include Ta-Nehisi Coates, and Thomas Chatterton Williams:

The one-drop rule—which classified any person with even one Black ancestor (“one drop of Black blood”) as 100% Black—officially came to an end in the United States only in the year 2000, Williams informed me, to my astonishment, when the U.S. Census Bureau abandoned the “Black” and “white” binary.

[…] In the early 1940s, this system was adopted by several states and at the federal level by the U.S. Census Bureau. For the following 60 years, biracial children—today the fastest growing demographic group in America—ceased to exist, as far as the government was concerned. They were simply Black.

They only officially resurfaced in 2000, when the Census Bureau’s abandonment of the Black-white dichotomy coincided with the coming-of-age of a large number of biracial children—the children of the civil rights generation. Visible for the first time at this scale, Americans like Barack Obama, Lenny Kravitz, Nikole Hannah-Jones, Thomas Chatterton Williams, and the novelist Danzy Senna, among many others, could now legally identify any way they liked—Black, white, biracial, multiracial, or nonracial. But this was not the way they grew up. They grew up as Black.

Children of mixed race were not given the privilege of containing Walt Whitman’s “multitudes” - not on a census, until the year 2000. However since then some, like Thomas Chatterton Williams, have embraced the notion that, in the words of Albert Murray, America is “incontestably mulatto,” while others like Nikole Hannah-Jones have steadfastly internalized their own version of the one-drop rule: the reality, as they see it, and as Hannah-Jones’ father inculcated in her, that they were black, and “would always be black, because in America such things do not change.” (This debate plays out in the article when Hannah-Jones, in a characteristically combative retort, flatly rejects Williams’ assertion that there is a certain cultural capital, particularly among biracial members of the black community, in leaning into one’s black identity.)

Aside from presenting multiple perspectives, it is the observations about America in this debate, from an outsider’s perspective, that make Weitzmann’s article a deep cultural investigation and much more than a one-dimensional profile of a popular journalist. After having drinks with Nikole Hannah-Jones’ retired, white middle-school teacher - who, inspired by his former pupil’s success, bought Ibram X. Kendi’s How to Be an Antiracist (2019) and purchased the web domain “undergroundclassroom” (in case there’s a reactionary fascist “setup” in response to the success of the 1619 Project, and Hannah-Jones’ “forbidden history” of America is banned and can no longer be taught) - Weitzmann notes:

I refrained from telling [Hannah-Jones’ teacher] that from where I stood, a Pulitzer Prize winner and the most famous employee of the The New York Times, whose work has received tens of millions of dollars in grants from the Ford Foundation, the MacArthur Foundation, and the Knight Foundation, who is a tenured professor at a university as prestigious as Howard, and whose work is now a part of the school curriculum in many states—and is also being turned into a docuseries by Oprah Winfrey and Lionsgate Entertainment—hardly seems “underground.”

I recognized in [Hannah-Jones’ teacher] that evening a kind of irreconcilable—and in my view, quintessentially American—conflict between veneration for individual success within the system, and an impulse for rebellion against the system.

To be fair to Hannah-Jones’ teacher, the rightwing backlash against The 1619 Project did include attempts to have the word “slavery” replaced with the fatuous term “involuntary relocation” in Texas public schools (which the Texas School Board unanimously rejected). Leftwing backlash, meanwhile, directed at the president of the American Historical Association, James H. Sweet’s mild criticism of The 1619 Project, Tweeted by a group of (mostly white) activist historians, insisted that calls for corrections should be suppressed, using the “perfectly circular logic” that any criticism of the 1619 Project would be weaponized by the right. The factual errors needing correction in 1619, meanwhile, are precisely what made it susceptible to political weaponization.

Another of Weitzmann’s observations about the American mentality comes from an American professor:

I had started to try to understand this admittedly alien debate while traveling in New York […]; for me, the most memorable comment about it came from a friend who teaches literature at Columbia University (who asked to remain anonymous). “What about the inaccuracies?” she asked me, by way of explaining her support of The 1619 Project despite the historians’ objections. “Are John Ford movies accurate? Were history books of the ’50s accurate?”

“This is America,” she said. “We vulgarize everything.”

By “vulgarize” I take the professor to mean that American democracy turns everything, including high art, scholarship, history and science, into popular fodder. And indeed we are the midbrow nation, mixing the high with the low, especially, it seems, in New York. It’s what Bob Dylan did famously, and what Walt Whitman did before him, in a torrent of emotional grandeur. Paul Berman, in the Brooklyn “Streets That Spawned a Masterpiece,” wonders if,

popular culture and the passing theories of the moment counted for more in Whitman’s world than the “high” culture of serious literature […] in New York a high culture has always managed to flourish in the most modest of neighborhoods. That may be New York’s greatest peculiarity.

Phrenology, mesmerism, these 19th c. theories of the moment exist side-by-side with the literary transcendentalism of Ralph Waldo Emerson in the pages of Leaves of Grass, according to Berman.

America’s tendency to “vulgarize everything” may have something to do with our tendency to commercialize everything, including our loftiest ideals. It certainly appears so in the years since 2020. Weitzmann’s article concludes in Houston, a few months after the release of The 1619 Project, where Nikole Hannah-Jones was invited to give a speech “to inaugurate the Emancipation Park Conservancy’s new lecture series, Emancipation Conversations, ‘establishing a forum for transformative conversations surrounding the Black Experience’”—sponsored by Shell Oil company, implicated in massive human rights abuses committed by the Nigerian government, including rape, torture, and the murder of an activist writer.

Such scenes [Hannah-Jones’ Shell Emancipation speech] make it hard to hold in one’s mind, simultaneously, the genuinely unjust racial and economic conditions into which Hannah-Jones was born, and the heights of power and affluence she has nevertheless scaled—and to regard this trajectory of her turbulent life not only as essentially unchanged, but as a fair representation of the impossibility of meaningful change in the lives of African Americans. That her own life has transformed so dramatically—and in precisely the self-made, bootstrapping, deliriously ambitious manner that Americans venerate above all else—cannot but suggest a certain ambivalence, or else a degree of mythologizing, behind the theory of America she submits. Indeed, at nearly every step of her journey—from [the] classroom to The New York Times—she has been encouraged not to puncture America’s traditional founding myths with the weapon of historical or journalistic truth, but to swap one set of myths for another.

In the words of Walt Whitman, “GREAT ARE THE MYTHS . . . . I TOO DELIGHT IN THEM.”

There is also the possibility, of course, that in trying to understand something about Americans by trying to understand Nikole Hannah-Jones, I simply failed. Perhaps it is because I am a European Jew with generally warm feelings about the United States, but I cannot be brought to see American society—which is caught again in one of its routine fits of mass cultural upheaval, whose aftershocks ripple across the oceans and remind all the world of its cultural domination—as intrinsically incapable of transformation. What, after all, is the current attempt by so many Americans—Black and white, liberal and conservative, elite and populist—to overthrow and move beyond the memory of the Civil Rights Movement, the most sparkling moment in all their history, if not a clear demonstration of it? If nothing else, it seems, America is a country with a frightening, almost maniacal capacity for change—however brilliant, however destructive.

In other words,

Great are the plunges and throes and triumphs and falls of democracy, Great the reformers with their lapses and screams, Great the daring and venture of sailors on new explorations.

Great are yourself and myself, We are just as good and bad as the oldest and youngest or any, What the best and worst did we could do, What they felt . . do not we feel it in ourselves? What they wished . . do we not wish the same?

— “Great Are the Myths,” Leaves of Grass, 1855