In a stunning turn of recent events, my next “sketch of Spain” happens to outline the story of an burgeoning Islamic caliphate overthrowing the ruling dynasty in Syria, sending its only surviving heir fleeing into exile, over a thousand years ago — the same week that the house of Bashar al-Assad fell to Islamist insurgents in Damascus.

This sketch of Spain also concerns the so-called “matter of France” — the body of medieval epic poetry, and the foundations of French national identity, describing the chansons de geste, or “songs of deeds,” about Frankish military engagements with Muslims before the Crusades.

As history happens to rhyme, the modern Syrian state, beginning in 1918, was a French “Mandate” — a colonial territory carved out of the defeated Ottoman empire after World War I.

In two centuries Syria has gone from being part of a relatively tolerant Islamic empire, to a French colony, to most recently, a proxy for an Islamist theocracy. To… what remains to be seen. It’s worth clocking warlord Abu Mohammad al-Jolani’s announcement last week that, “Muslims and Christians in all their diversity will be respected” in the new Syria — and comparing whatever develops to the culture of tolerance I’m about to discuss, amongst Muslims, Christians, and Jews in medieval Spain, initiated by a Syrian exile in the year 755.

These are but superficial parallels, perhaps, but I can’t help thinking of them as I recall the origins of a “cathedral” I recently visited in Andalusia, known as the Mezquita (“mosque”). A hybrid architectural wonder: the Great Mosque of Cordova, Spain, constructed over a paleoChristian church, and perhaps a pagan Roman temple, now a church again — though only officially, and probably only to Spanish Catholics.

The Great Mosque of Cordova is, “an example … of loving dialogue with the past, a way of bringing the past to life, or of rewriting it so it is intelligible in the present,” in the words of medievalist Maria Rosa Menocal.

So, perhaps I can only attempt the same.

In 750 C.E., the second Islamic caliphate (from khalifa, or “successor,” to Muhammed) was overthrown in a violent coup in Damascus.

The pretenders to the House of Islam, the third caliphate, generally depicted by Muslim historians as the founders of the Golden Age of Islam, the Abbasids, replaced the Umayyad dynasty in Syria. Abbasid insurgents massacred every last member of the Umayyad family save one: a young prince, fifteen to twenty years old at the time, named Abd al-Rahman.

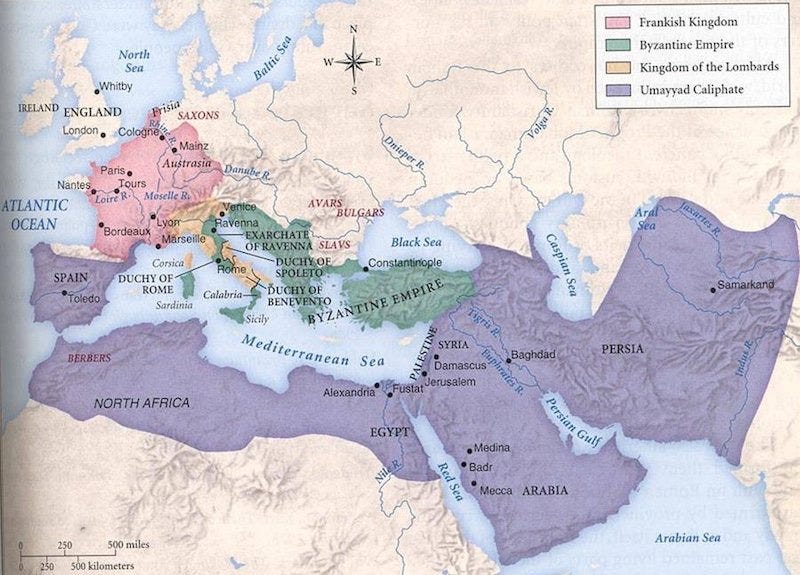

The Umayyad caliphate, which had moved the capital of Islam out of the factious Arabian desert with its warring tribes, from Mecca and Medina to the far-more diverse and cosmopolitan city of Damascus (first Greek, then Roman, Christian, and Muslim), had already conquered most of North Africa and Iberia by the time it was overthrown in 750.

In 732, the Umayyads who preceded Abd al-Rahman (before they were massacred in a coup) had expanded nearly to Paris, as far northwest as Tours, where they were finally driven back by the grandfather of Charlemagne, the great leader of the Franks. If the Battle of Tours had gone differently, as Edward Gibbon remarked in The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, “perhaps the interpretation of the Koran would be taught in the schools of Oxford.”

In the years that followed the Abbasid Revolution, the young Umayyad Abd al-Rahman would also engage the Franks. French epics like the Song of Roland, concerning the battles of the first Holy Roman Emperor, Charlemagne, against Muslims, were the stuff of early French romance, which became the stuff of early French roman — later known in English as, “the novel.” Chivalric romance and chansons de geste.

The stuff of early French literature is, well, mostly “stuff.” The Song of Roland recounted by troubadours and early French writers told the story of one of Charlemagne’s military commanders, count Roland, being massacred in a mountain pass as he fled Abd al-Rahman’s troops in the Pyrenees. Centuries later, during the crusades, The Song of Roland became a fictionalized example of Muslim perfidy against Christendom.

But count Roland, though he was indeed fleeing Abd al-Rahman’s troops, was killed not by Muslims but by fiercely territorial Basques — local Europeans, whose mountains he was passing through. This defensive regionalism persists today — Basques, like Catalans, are fiercely independent, even secessionist, in modern Spain. I recall sitting on a park bench twenty years ago in the Plaza Catalonia, next to a man who casually told me he was “terrorista, soy ETA” — a Basque separatist militant.

After the Abbasids took Damascus in 750, the upstart caliphate moved their seat of power east, away from any lingering traces of Umayyad sympathy and legitimacy in Syria — to a new city, not far from the site of ancient Babylon, which they called Bagdad, “the City of Peace” — where so many Arabian Nights are set, many of them depicting the great patron of the Golden Age of Islam, caliph Harun al-Rashid.

The refugee from this fallout with the Abbasids, the young Abd al-Rahman, the only surviving Umayyad, went west, “Aeneas-like,” in the apt description of Menocal, fleeing his conquered capital, like the defeated Trojan who founded Rome. After crossing the deserts of the Magreb and the strait of Gibraltar, in 755, he appeared “like a mirage” in Andalusia, in southern Spain.

The emir (“governor”) of Cordova, which had previously been a far-flung outpost of the Umayyad empire, had already taken the shift to distant Abbasid rule in stride. But when the surviving heir to the Umayyad dynasty, presumed dead for five years, appeared in his city, it must have come as an unwelcome shock. The Emir offered the prince his daughter’s hand in marriage, and a chance to govern Andalusia together. Abd al-Rahman had other ideas.

In the dynasty’s westward expansion in the century following the Prophet Muhammed’s death, the Umayyads had successfully fought, subdued, and converted the Berber tribes of the Magreb, or “Far West,” before advancing from North Africa into Iberia and briefly, France, the limits of Muslim conquest. By the time of Abd al-Rahman’s surprise appearance in Andalusia, the Umayyads’ former Spanish territory, al-Andalus, was riven by conflict between Berber Muslims from North Africa — those recently conquered, converted, and conscripted by the Umayyads — and Syrian Muslims from Damascus, patricians who boasted a genetic link to the Bedouin tribes of Arabia, and thus, to the Prophet himself. To say nothing of the conflict between Muslims and Visigothic Christians, the descendants of the pagan barbarians who had invaded the Roman Empire and later converted to Christianity — a form of Christianity at odds with Roman Catholicism. And, those adhering to the vestiges of paganism itself.

The territory that the Umayyad prince Abd al-Rahman arrived to from Damascus was, in short, ethnically, politically, and theologically at war with itself. But the prince had a wild card.

Abd al-Rahman’s mother was a Berber tribeswoman, a queen or concubine taken to Damascus during the Umayyad conquest of North Africa. On his father’s side he was Arabic, a Syrian transplant descended from the Bedouin tribe of Muhammed. And the Umayyads in general were adept at cultural syncretism, absorbing the spoils and trappings of the civilizations they met as they spread westward, incorporating them into a hybrid aesthetic of politics and religion.

The Great Mosque they erected in multiethnic Damascus — which, per Abd al-Rahman’s instructions, the Great Mosque I visited, in Cordova, would one day strive to imitate — was also built on a repurposed Christian church, which had previously been a Roman temple. And it was the Umayyads who had erected the (Muslim) Dome of the Rock atop the (Hebrew) Temple Mount, on the hill where Abraham was spared the sacrifice of Isaac, in Jerusalem. To Menocal and others, this is evidence of Umayyad cultural “diversity,” a willingness to tolerate, and even embrace as part of one’s own, the culture of others — especially the three religions of Abraham, or “People of the Book.” It is a diversity that characterizes the best of pre-modern Spain, instilled, mythically at least, in the figure of Abd al-Rahman, who turned his multicultural heritage to his advantage.

When the Emir of Cordova, nominally under distant Abbasid rule from Bagdad, offered the Umayyad prince his daughter’s hand in marriage and a chance to govern al-Andalus under the Emir’s direction, the Umayyad — himself half Berber, half Syrian — raised an army of Berber and Syrian Muslims to overthrow the regime. Over the next three decades, he built a peaceful empire that raised the status of beleaguered Jews on the Iberian peninsula, much to the initial dismay of local Christians, who eventually accepted the dominance of a tolerant Muslim majority, under a ruler who enriched all three cultures more or less equally, and married a Jewish woman himself.

Abd al-Rahman’s empire was a caliphate “in all but name,” in Menocal’s telling. In 939, less than two centuries after his death, a successor, Abd al-Rahman III, felt emboldened enough to declare his reign the Caliphate of Cordova, a cultural rather than military rival to the Abbasid Caliphate in Golden Age Bagdad.

Within a century of this designation, however, the Cordovan Caliphate would be overrun by first one wave, then a second, of increasingly fundamentalist Berber Muslims invading the peninsula from a new polity in North Africa, now known as Morocco, the home of the Moors.

It was these zealots who became the foot soldiers in the downfall of the Umayyads, and it was these “Moors,” as they are reductively known, who would be cast as the villains in the Reconquista, or Christian conquest of Spain in the centuries leading up to 1492.

What actually transpired during this period was the splintering of a once unified empire into local taifas, solitary kingdoms not unlike the competing city states of Renaissance Italy — in the south mostly Muslim, in the north mainly Christian — who fought against or alongside each other in their quest for cultural dominance and prestige, and often, in their quest to repel fanatics of either stripe.

But even during the divisive period of the taifas (from roughly 1031 until the last Muslim emirate, Granada, fell to Ferdinand and Isabella in 1492, marking the beginning of Catholic Spain, and the end of its religious diversity), something like Abd al-Rahman’s pluralism flourished in Iberia. Translations of pagan Greek philosophy poured from Bagdad into Andalusia, where they were translated from Arabic into Latin and later, Castilian, and transmitted to the rest of Europe, especially France and England, who also embraced the music of the region, and its Arabic instruments.

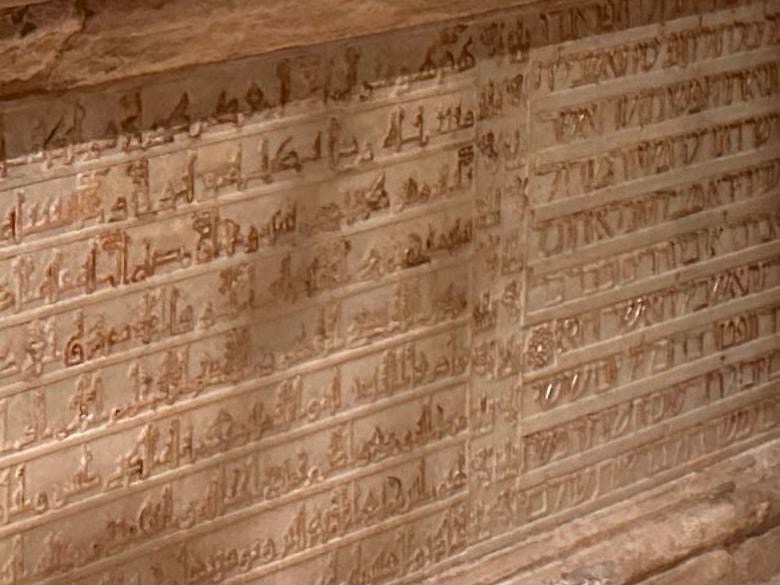

Even the supposed saint of the Reconquista bears the marks of Islamic Spain’s multiculturalism. In Seville, the tomb of Saint Ferdinand — who took Cordova (1236) and Seville (1248) from “the Moors,” marking the end of Muslim rule except in the Emirate of Granada — is inscribed in the diverse languages of Andalusia: in Castilian, Latin, Hebrew, and Arabic.

As if to highlight the fact that this multicultural history is overlooked, the tomb of Saint Ferdinand lies in a side-chapel of a curtained-off alcove in the Seville Cathedral, the largest Gothic cathedral in Europe. Entry to the diminutive chapel is free, during the few hours it’s open; I had to seek it out, and when it did open, the tomb was mostly visited by devout Catholics attending evening mass. The rest of the Cathedral of Seville is open daily, entry costs 25 Euros, and the tomb most visited there is the sepulcher of Christopher Columbus, who sailed for a different Ferdinand, and his queen Isabella, in 1492.

The Arabic and Hebrew, and the Castilian that these two Semitic languages midwifed, on the tomb of a Catholic saint in Seville is the result of Abd al-Rahman’s willingness to utilize the bits and pieces of culture he found at hand — the religions, languages, architectures, and building materials that were already present in Andalusia when he arrived, combined with those of his own.

Those bits and pieces include the ones Abd al-Rahman used in the construction of the Mezquita, or Great Mosque of Cordova, which began at the end of his life.

The floor tiles of the pre-Islamic, Visigothic church of San Vincente are still visible to modern visitors through a plexiglass window, beneath the floor of the Mezquita. The Corinthian columns which the dizzying array of red-and-white arches atop red-and-white arches rest upon are original Roman, and later, as the mosque expanded under al-Rahman’s successors, imitation Roman columns.

The Great Mosque is, in Menocal’s words:

very much about the Umayyads’ care not to destroy the multiethnic and religiously pluralistic state. The aesthetics of the new Cordovan mosque … was typically Andalusian from the start: part adaptation of local, vernacular forms and part homage to Umayyad Syria…

The orientation of the Great Mosque, like all mosques, should traditionally be constructed to point towards Mecca — in this case, from Cordova, to the east. But the Great Mosque in Cordoba, like its culturally-hybrid predecessor in Damascus, points south, in the direction of Mecca from Syria, in memory of Abd al-Rahman’s lost Syrian home.

The edifice, which has grown in stages reflecting the successors of Abd al-Rahman — expanded by family heirs, Berber Muslims, and Catholic kings — is an homage to memory and exile.

The trees in the courtyard, oranges and palms, are transplants from Syria. The aging king wrote an ode to one of them before he died, to a reconstructed version of his family home, named Rusafa.

A palm tree stands in the middle of Rusafa,

Born in the West, far from the land of palms.

I said to it: How like me you are, far away and in exile …

The king’s poetry, poignant but middling, is for Menocal a reflection of Islam’s grounding in poetic language, the pre-Muslim tradition of pagan Arabia.

When the Prophet Muhammed brought his “recitation” (Quran) of God’s words to the sacred black stone in pagan Mecca — the Kaaba, now circumambulated by Muslim pilgrims — he was essentially bringing his words to a pre-Islamic poetry recital. The winning poems in this contest were written in gold on banners and hung around the Kaaba — the “suspended odes,” or “hanging odes” of pre-Islamic Arabia. A tradition that Abd al-Rahman brought to Spain.

Although he was not himself a brilliant writer, Abd al-Rahman’s legacy is as critical as the Great Mosque itself, his poetic tradition a palace that houses the memories of the oldest ancestors.

The Great Mosque itself, with its admixture of religious and architectural languages, which artisans of multiple religions have contributed to over the years, is a form of “visual poetry,” which Menocal compares to the secular love songs of Andalusia yet to come:

the culturally hybrid sung poetry the Andalusians invented about the time of the proclamation of the caliphate, nearly two hundred years later, a mixture of old and new, classical and vernacular, called “ring songs”.

These are the love songs I described in my last sketch of Spain, “Songs of the Virgin” — secular songs that extend from Muhammed and Mary but end in “shut up and kiss me.” Songs that inspired the troubadours, Petrarch, and Dante.

The Mezquita is symbolic of Andalusia’s multicultural heritage in other ways that have little to do with the vision of Abd al-Rahman I, but are nonetheless stunning examples of syncretism. The lamps hanging in the mosque were at one time constructed of iron melted down from the church bells of Santiago Compostela.

A Muslim usurper to the dynasty of Abd al-Rahman expanded his territory by attacking the Christian settlement to the north that housed the alleged remains of Saint James (Santiago) the Apostle, and brought the bells back to Cordova as a trophy — an event that, ironically, turned a little-known monastery into a pilgrimage site, made Santiago the Patron Saint of Spain, gave us the name Matamoros (“Moor-killer”), and catalyzed the Reconquista leading to the expulsion of the Moors.

A Catholic bell tower later added to the Mezquita…

… conceals a minaret:

The roseate stained glass windows painting the air of the mosque are clearly Catholic, and the Baroque cathedral walls they stain in vibrant colors were commissioned, right in the center of Abd al-Rahman’s mosque, by Charles V in the sixteenth century. When he saw the results, the Catholic monarch complained to his architect, "You have built what you or anyone else might have built anywhere; to do so you have destroyed something that was unique in the world.”

It’s a testament to the ability of one aesthetic school, a school of acceptance, to incorporate a variety of styles into an artistic whole, unique in the world, versus a culture of awkward imposition.

Or worse, a culture of destruction. Muslim Andalusia compared to Catholic Inquisition, for example, or the syncretism of the Umayyad caliphate compared to the destruction of UNESCO heritage by the Islamic Caliphate. Abd al-Rahman, compared to Bashar al-Assad, or whatever comes next.

The “mosque” in Cordova is no longer open to public prayer. One of the last notable Muslims permitted to pray here, was Saddam Hussein.