Two Masterpieces of 70s Journalism

Tom Wolfe's "The 'Me' Decade" and Joan Didion's "The White Album" help explain the 1960s and 70s--and the 2020s

The 1960s and 70s were characterized by an American literary movement known as New Journalism.

Combining the techniques of fiction with journalistic research, often inserting the author into the story, New Journalism pushed the boundaries of traditional reporting, and questioned the possibility of truly “objective reporting.”

Its key practitioners include Tom Wolfe, often credited with innovating the form, Joan Didion, Truman Capote’s “reportage” on the Kansas murderers in his “non-fiction novel” In Cold Blood, and the outrageous brand of New Journalism that came to be known as “Gonzo,” articulated by Hunter S. Thompson—who famously claimed “there is no such thing as Objective Journalism. The phrase itself is a pompous contradiction in terms,” in Fear and Loathing on the Campaign Trail 1972. “Objective journalism is one of the reasons American politics has been allowed to be so corrupt for so long.”

With the recent suggestion by the editor-in-chief of the San Francisco Chronicle that journalistic “Objectivity has got to go”—a tendency towards political activism and advocacy among a new generation of reporters described in these two articles (one “left”-leaning, one “right”)—I wonder at the legacy of New Journalism in the twenty-first century.

The non-objectivity in contemporary journalism and the New Journalism of old share something in common—but the latter was a lot more fun, creative, and probing.

And revealing. As David Johansen recently defined “camp” in Martin Scorsese’s Personality Crisis: One Night Only, the fictional masquerade in certain pieces of New Journalism—in Hunter Thompson’s case at least—was often “the lie that told the truth.”

Frank Mankiewicz, George McGovern’s campaign manager, said of Thompson’s reporting that year that it was “the least factual, most accurate account” of the 1972 election of Richard Nixon.

Below are two essay-length masterpieces of New Journalism, explaining parts of the revolutionary era that was the 1960s and 70s—and if you read closely, parts of our own. Unlike some of Thompson’s work, they’re not outrageously fictionalized or embellished, but deeply personal first-hand accounts.

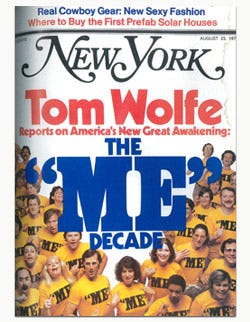

Tom Wolfe Reports on America’s New Great Awakening,

The “Me” Decade (1976)

There’s a “meme” circulating—more accurately, a theory—that with the decline of traditional religious affiliation in America, the nation is undergoing a bizarre new form of secular religious revival.

Some point to QANON, others to Psychedelic Therapy, Critical Race Theory, Transgender Activism, Trans-humanism (merging with computers to achieve god-like immortality), the “witch hunting” of cancel culture, and devotion to Politics. Sherman Alexie recently described the spiritualization of “capital ‘I’” Indigenous culture among non-Indians and “plastic shamans,” in this, incredible essay. Matt Taibbi claims “The News is America’s New Religion”—invoking anchorman Howard Beale’s wild on-air sermon from the 1976 film, Network.

One cheeky wag has dubbed this recent phenomenon “the Great Awokening.”

Whatever you call it, and whatever outlet it may assume, there seems to be some psychological truth behind this narrative, based on the fact that so many people want to describe it this way.

Tom Wolfe—the journalist and author behind such classics as The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test (the Ken Kesey, Merry Pranksters chronicle) and The Right Stuff (later adapted into the definitive space-race film)—wasn’t the first to describe an American “Great Awakening.” There have been numerous religious revivals throughout our past, chronicled by historians.

But Wolfe was the first to apply the term to the new secular-spiritual practices of the 1960s and 70s. And this article is undoubtedly the ur-text for similar interpretations in the new millennium. The Great Awakening is one of our recurring national motifs, right up there with the Salem witch trials, and has been invoked once again.

If you’ve ever seen the 2014 film adaptation of Thomas Pynchon’s Inherent Vice, starring Joaquin Phoenix… look-up a few of the characters and organizations mentioned in Wolfe’s piece (like Synanon), and compare them to the film. You’ll find that truth is stranger than fiction.

Inherent Vice appears more realist, after reading “The ‘Me’ Decade.” And…

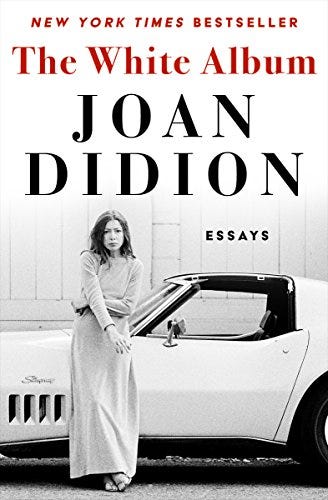

Joan Didion’s titular essay from her bestselling collection,

“The White Album” (1979)

Didion was the 1960s female embodiment of detached authorial cool… but she was actually, well—conservative’s definitely not the word—but skeptical, when it came to some of the myths of 60s and 70s counterculture. And confessionally neurotic in this piece, the only reasonable response to the turmoil she describes within.

In the titular essay from her other renowned collection, Slouching Towards Bethlehem (1968), Didion poked holes in the supposed utopianism of the Haight-Ashbury scene, hanging out with the district’s homeless teenage denizens, with the Grateful Dead, Big Brother and the Holding Company, other musicians, and Chet Helms of the Diggers… concluding with the horrific yet determinedly non-moralizing scene of a five-year old whose mother feeds her LSD.

In “The White Album,” Didion dismantles the sex-death mythos of the Doors (a band that fascinated her—“the Norman Mailers of the Top 40, missionaries of apocalyptic sex”)—by describing their artistic process one evening in 1968. Sitting-in on the recording of their “third album,” presumably Waiting for the Sun—which might as well have been called Waiting for the Singer, in Didion’s telling.

The writer watches and listens as musicians and engineers putter around the studio, while keyboardist Ray Manzarek eats hardboiled eggs out of a paper bag and wonders about his lead singer, wasting away the evening as everyone waits for Jim Morrison to finally arrive at Sunset Sound studios—only to take to the couch, light a match, stare at it unto extinguishment, and slowly lower it to the fly of his leather pants.

She comments wryly on the impossible libation demands of rock stars as she mixes Janis Joplin the “brandy-and-Benedictine in a water tumbler” she requested at a party one night, at Didion’s seedy-edge-of-Hollywood home.

She visits Huey Newton in the hospital, and other Black Panther founders elsewhere.

Interviews Linda Kasabian about her involvement in the Manson Murders, and meets one the killers of notorious silent-film actor Ramon Novarro.

Finally, and perhaps most tellingly, she attempts to understand the aimless agit-prop of campus activists in search of a meaningful cause, at San Francisco State.

Long reads both, but well-worth the time for anyone who wants to truly understand the terrific chaos of the 1960s and 70s, and perhaps some of our own. Two of the great pieces of New Journalism from the late 1970s, from two of the most masterful essayists of the twentieth-century—one comedic (Wolfe), one melancholy (Didion).