Welcome to Substack. Perhaps you’ve heard of it.

Perhaps not. As a Representative for the 29th District of Texas recently put it:

I guess it’s sort of like a webpage I don’t really understand what Substack is but, ah, that, all I can say is that…

It’s a self-publishing platform.

Remember blogs? It’s a “blog,” except the creators here can make a living.

Imagine if Spotify were created by a songwriter, and gave artists 90% of the income, and allowed them to retain the rights to their work, as opposed to a record company. This is that publishing service, for words instead of music.

As you might imagine, some great talent is migrating to this “blog.”

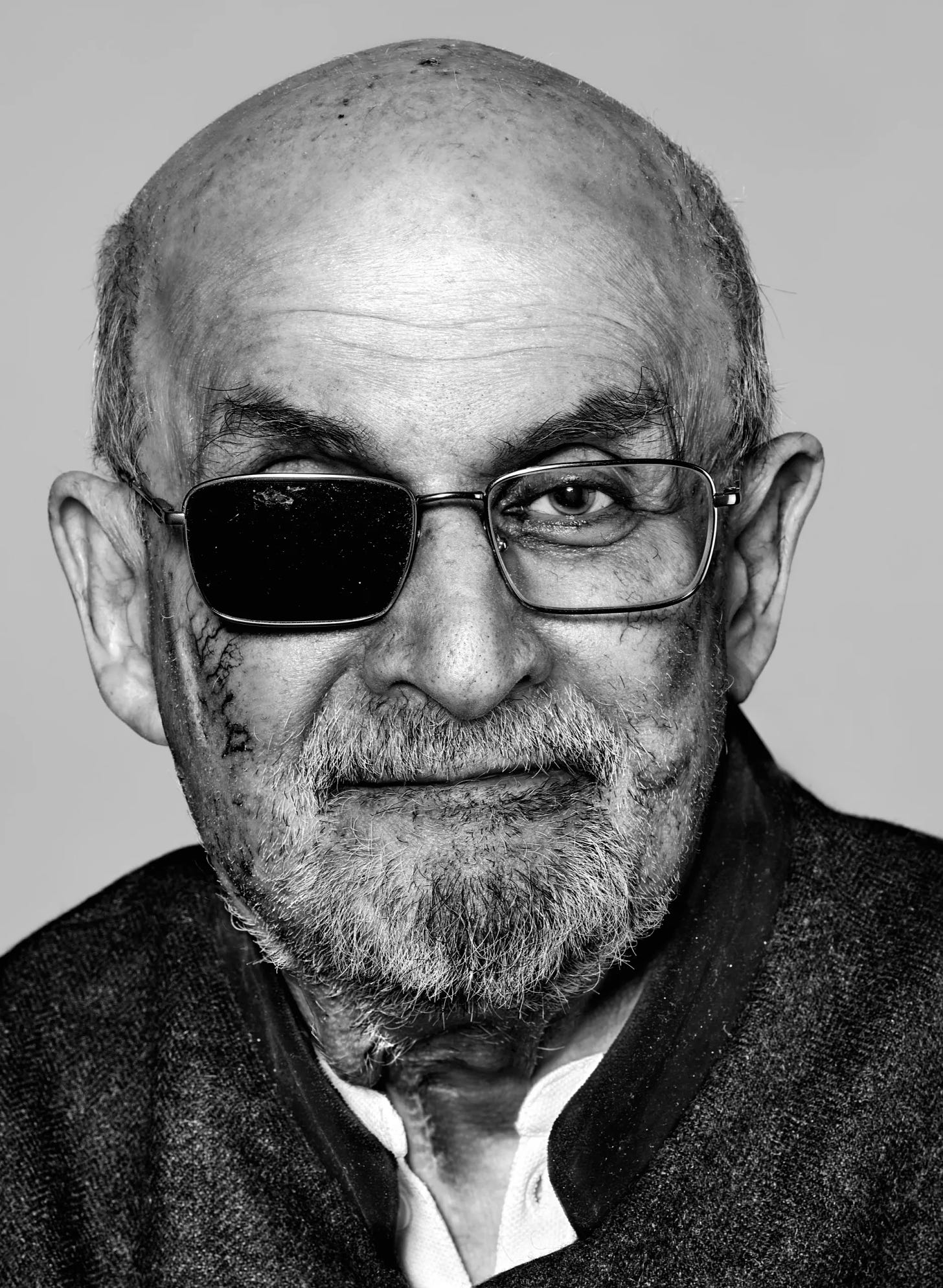

George Saunders, Salman Rushdie, Chuck Palahniuck, Sherman Alexie, Margaret Atwood, Patti Smith… just to name some of the major literary types.

Plus scores of nonfiction writers, professionals of every background, DC and Marvel creators, visual artists, and perhaps most encouragingly, a new school of honest journalism.

If Anthony Bourdain or Lester Bangs were alive today, they’d be here too.

I’m not an early adopter. I joined Twitter a year ago—for the journalism (seriously).

I’m nearly as clueless as the congresswoman I quoted, and twice as skeptical, when it comes to social media. But this is a good thing.

Something is “happening here.”

Rep. Sylvia Garcia, the politician trying to define Substack, was speaking to a journalist at the time. Someone whose work I’ve followed since he covered the 2008 financial crisis for Rolling Stone. He was testifying before Congress last week in light of groundbreaking reporting. The most explosive story of his career, published… here.

You may have noticed that journalism, like politics, publishing, and a whole grab-bag of other institutions, is shattered. The reason the reporter I mentioned ditched the most coveted job in countercultural journalism, for Substack.

The same reason another respectable journalist left the New York Times in 2020. I only discovered that journalist after she created her own news organization, launched here. Like a certain counterculture rag in its hey-day, the rest of the media has found itself playing catchup to her organization, following its lead on a number of stories.

A favorite music historian of mine (whom I’ll write about soon), has a convincing theory about the State of Culture in the 2020s: Counterculture has been evaporating. Drying up, washing out, and stagnating—for years.

We no longer have a healthy confluence of diverse opinions, united only in opposition to the main stream. An underground well of fresh art and ideas, springing up in all directions.

I have a related theory, which I believe my historian secretly subscribes to: the counterculture is here on this platform, as far as creative writing and journalism are concerned.

The historian I mention, already respected and successful in traditional publishing, fled that institutional security for greener pastures in 2021. He’s publishing his latest musical history, on Substack.

His book, like many others, is being published here in serial form. A practice once common at countercultural heavyweights like Playboy and Rolling Stone: publishing serial installments of a larger work written in quick succession, in magazines and periodicals. High, middle, and lowbrow literature, available in the popular arena.

Serialization was once the fast-paced delivery method for books such as Bonfire of the Vanities, The Right Stuff, Fear and Loathing, War and Peace, Madame Bovary, Heart of Darkness…. an intense creative outlet for authors like Hemingway, Faulkner, Dickens, Raymond Chandler, Agatha Christie, Mark Twain—too many to list here.

It’s encouraging to see the form returning, another sign of hope.

Why this, why now?

Last year, I started compiling a collection of essays for publication.

Submitting it to a small local press, I received positive feedback, and heard it would sell.

But after the better part of a year, things began to stagnate. Something was off.

I began to suspect the editor was simply receptive to my invoice payments, and little else. Just a hunch—like the gut feeling that my boutique press, proud like Rolling Stone of its embrace of “the F-bomb,” marketing itself as an outré forum for dissident voices… was actually quite conformist and timid.

What’s not a hunch, I was collaborating with a faceless entity. Failing to develop the rapport between writer and editor essential to any literary project: a reciprocal creative partnership.

The editors at this press came without biographies, or so much as a headshot. All collaboration was performed online, without phone calls or face-to-face interaction. Presumably for the sake of anonymity, and fear of controversy or reprisal.

The cloistered world of publishing, as I said, is in trouble.

Not without reason are publishing houses reluctant to give out personal information, or interact with authors in the flesh. A controversial book (which to the best of my knowledge, mine was not) will rebound hard on a publisher; they must protect themselves.

Due to this fear—combined with the fact that fewer people read, revenues are low, and the industry is in straits more dire than even the newspaper industry… literature suffers.

Not only are the imprints terrified; I was anxious. When words like “fat” and “attractive” are deemed offensive, and posthumously removed from the works of Roald Dahl… who’s to say what might be considered improper?

Today, it’s not uncommon for writers to sign “morality clauses,” indicating that in the case of unforeseen controversies or cancelation campaigns adjudicated by the public, the author agrees to suffer the consequences, alone. Mostly, this means retroactively depriving writers of advances and other contractual agreements, dropping them on the spot, if someone on the internet deems their work problematic.

The morality clause is a liability waiver, clearing the house of culpability. Never mind that publishers make an ethical judgement when they decide to publish a writer in the first place. A judgement-call publishers were, traditionally, proud to defend afterwards. Even in the face of fatwa or death threats, as was the case with Salman Rushdie.

People died, and many more risked their lives, to defend a book. Publishers, booksellers, translators and authors—together.

This is no longer the case, even at large conglomerates, “The Big Five” with vast resources compared to a local press.

Uncertain of my editing partnership, I asked to meet in person or on the telephone. Sent probing emails describing my personal beliefs about the state of culture; inquired about the state of the industry and the intricacies of the publishing process; and tried to read the tea leaves of my editor’s proofreading comments—to divine something about the person I was working with, to no avail. The usual response was a chipper “Hi!,” weeks later, when I had another manuscript to submit. For a nominal fee, of course.

As a final consideration, I took the advice of a favorite writer: publish first on Substack. Unlike most publishers, whatever appears in print here can be submitted elsewhere, later. The author owns the rights, not some faceless imprint.

In fact, the author owns the company. As of this morning, I am a shareholder.

This newsletter is an offshoot of that book of 2020 essays, maturing and reacting to subsequent events in real time. At a publisher I’ve invested my faith in.

What’s here?

Community.

Substack is more than epistolary journalism—the “newsletter” format now being copied by major magazines and newspapers, startled by its upstart success. I’ve seen firsthand how writers here have nurtured the very thing I was missing at my small local press: a community of like-minded people.

Better yet, a community of unlike-minded people, fed up with things as they are, engaged in a dialogue over shared interests. The audience as partner and ‘editor.’

Join this wayward bus and we will encounter new things, together.

It’s a two-way street.

What to expect

A weekly “newsletter” published every Friday afternoon—really, a guide to culture in the form of articles and essays. Extra editions will appear midweek.

Pro bono, gratis.

Every successful publication I’ve witnessed the birth of on this platform began with an optional paid-subscription format; even the juggernauts remain at least partially-free. I see no reason not to emulate the best.

Flatter me if you wish, but the only payment I ask is feedback and recommendations—recommend the Third Ear to others with shared interests, and share whatever you find interesting with the author and subscribers of this newsletter (use the comments section, or email).

The goal is growth and expansion… of culture. A highbrow-lowbrow intellectual community.

Subscribers enjoy:

Links to recommended authors and newsletters

Links to recommended podcasts

News stories worth following, which readers may not be aware of on either side of the divide in partisan journalism

Access to exemplary journalism from various eras, curated by me

Explainers and background for the journalism mentioned

Film, book, and event reviews

Art and culture recommendations

Literary and cultural criticism

Anthropology and history relevant to all of the above

In short, a guide to the humanities—human nature and culture—involving current events. More often than not, using music as an entry point.

I wouldn’t be doing this if not for the well-founded suspicion that many of the people closest to me do not have access to some of these resources. This is most conspicuous in the dearth of honest news and journalism (and the death of humanities studies), but also applies to that most precious of resources: time.

No one has time to read everything. Let alone watch, listen, attend, or research. Nor do I, alone.

That’s where a third ear comes in. It’s what’s between us. The Third Ear is a mediator. A middleman between the organs on the left and the right, and the ones in high and low places, it hears what the other two don’t. It’s a negotiator. What one of my historians and music critics calls an “honest broker.” I’ll bring you what I know; you tell me what I’m missing.