"What do you think about Osama bin Laden? What do you think about the Strokes?"

How 9/11 created an international hipster stereotype

There’s no need to be an asshole, you’re not in Brooklyn anymore.

Sam France, of West Coast psychedelic ensemble Foxygen, uttered these words ten years ago. He was deriding the existence of a new caricature on the American scene: the Brooklyn hipster. The borough’s most coveted neighborhood, Williamsburg, had succumbed to gentrification and stereotype. Artists like TV on the Radio, who made the neighborhood attractive to the new species of hipster in the first place, were priced out. The Strokes were winding down the first act of their careers in the East Village, and Karen O. of Yeah Yeah Yeahs was fleeing Brooklyn in disillusionment, as Manhattanites poured across the East River. Streaming continued to ravage the music industry. And “asshole” became a demonym for Brooklyn - at least in the lyrics of the last great rock and roll band from Westlake Village, California.

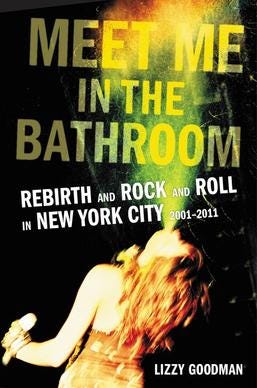

The ‘last great era of rock and roll bands’ is how reviewers tend to describe the period chronicled in Meet Me in the Bathroom (2022), a documentary film based on Lizzy Goodman’s oral history, Meet Me in the Bathroom: Rebirth and Rock and Roll in New York City 2001-2011.

Goodman’s book follows the lead of Legs McNeil and Gillian McCain’s Please Kill Me: the Uncensored Oral History of Punk (1996), by presenting the complimentary recollections of artists, journalists, and management, from the early naughties instead of the seventies. At the center of Goodman’s book are, in the words of one publicist, “a bunch of Holden Caulfields.” Millennial Manhattan’s first overnight success story - J.D. Salinger’s disaffected, privileged anti-hero from Catcher in the Rye, times five - the Strokes. At the center of the film version is the startling transformation - from shy Korean-American “halfie” to Iggy-Pop-intensity front woman - of Karen O., lead singer of Yeah Yeah Yeahs.

Both groups owe part of their resolve, and their perception (deserved or not) as “underdogs” to the tragedy of 9/11. Karen O.’s story is perhaps more inspiring in the film - watching her transform from an awkward girl into a dangerously physical performer during Yeah Yeah Yeah’s first show (opening for the White Stripes at Mercury Lounge) is mesmerizing - but it was the initial success of the Strokes that broke the dam for everyone, made them emblems of post-9/11 New York, and modeled an aesthetic soon embraced by the rest of the world. Especially after the Strokes, like Yeah Yeah Yeahs and others, were whisked away to England for their first international tour, where fans hungry for news from New York were waiting.

There were many admirers.

Meet Me in the Bathroom is the title of Goodman’s book and film; it’s also the penultimate track from the Strokes’ sophomore album, Room on Fire (2003). Allegedly, about songwriter Julian Casablanca’s druggy sexual encounter with the nineties’ most infamous hanger-on and (depending on your tastes and stomach) sometimes-talented contributor, Courtney Love. (Love wrote her own version of the tryst with Casablancas, the lyrically-demented “But Julian, I’m a Little Older Than You”.)

A sloppy passing of the torch from the prima donna of grunge to the first man of the indie underground - a rite de passage, when Courtney Love (along with Winona Ryder) invites you to “come be famous” and slurs the husky words, “Meet me in the bathroom.” Casablancas must’ve appreciated the inebriate flattery, and potent symbolism, of inserting himself into rock’s Black Legend; same goes for Love and the center of attention. Vampire symbiosis. A testament to how big, and superficially linked to the MTV generation, the NYC music scene had become in the fast year since September 11th, 2001.

One wonders why the first lady of grunge didn’t lend some of her support to the scene’s feminist icon, Karen O., along with the Strokes. Then again, the Yeah Yeah Yeahs front woman seems to prefer Love’s contemporary, Kim Gordon of Sonic Youth as a role model. According to Goodman’s book, she also called Love a few choice words before pushing her into a catering table at SXSW in 2002. Kim Gordon, for her part, had this to say about the woman who stole her husband and bandmate, Thurston Moore, in Girl in a Band (2015):

No one could understand how Thurston, who always had a good nose for the user, the groupie, the nutcase or the hanger-on, had let himself get pulled under by [Love].

And,

No one ever questions the disorder behind her tarantula LA glamour — sociopathy, narcissism — because it’s good rock and roll, good entertainment! I have a low tolerance for manipulative, egomaniacal behavior, and usually have to remind myself that the person might be mentally ill.

One can argue whether or not the decade between 2001 and 2011 was truly the tail end of edgy rock and roll, before the Internet and iPod jumbled all genres into one squeaky-clean composite represented by Vampire Weekend - but it was indisputably the last gasp of the traditional recording industry and MTV. You can hear the death rattle on 24 Hours of Love, a media stunt from MTV2 hosted by Courtney Love in September 2002, a year after 9/11, in which she commandeered MTV’s sound stage in Times Square, attempted to remain chemically alert for 24 hours, and invited Louie C.K., Ryan Adams, and members of the Strokes to participate. Two of them were so enthralled they passed out and slept on live national television.

One can argue whether the era in Meet Me in the Bathroom was dangerous and exciting or, as Karan Mahajan suggests in the New York Review of Books, a lightweight revival of the gritty Bowery era depicted in Please Kill Me. Whether it should come as no surprise “that this movement prospered when New York itself was becoming a safe playground for white people under Giuliani” and Bloomberg. On the other hand, even as late as 2000, the city was still gritty. The acronym for Alphabet City stood for “Alcohol, Blow, Crack, Death,” according to the DJ known as Moby, while across the river, Brooklyn “had the worst of both worlds—it was seen as both being where your grandma’s from and also a place where you’re going to get killed,” says a promoter. “I mean, you couldn’t even get cabs out to Williamsburg,” adds TV on the Radio’s Dave Sitek. “Giuliani cleaned the place up,” says comedian Mark Maron, “but it was still kind of menacing.” Luna’s Dean Wareham: “He did clean things up. You couldn’t buy drugs on the street anymore. But fortunately cell phones came in.”

Urged on by New Yorker columnist Malcolm Gladwell’s specious “broken windows” theory, Giuliani implemented “stop and frisk,” cleared up the street-dealing, and was reviled by twenty-somethings on both sides of the river.

While the mayor cleaned up parts of Brooklyn and the Lower East Side, New York was about to become a new kind of dangerous, and paranoid. Giuliani’s image was about to receive a national makeover: “All of a sudden Rudy Giuliani went from being someone everyone hated to someone everyone loved” because of 9/11, says Dean Wareham. As for the new sense of danger - you can see it in Karen O.’s dancing. And hear it in Strokes guitarist Albert Hammond Jr.’s description of going to visit a friend in the hospital with Julian Casablancas on September 11:

… it was like paranoia on the streets. Someone’s cell phone wouldn’t stop ringing, and they couldn’t stop it and everyone started to run away from them because they thought it was a bomb. So we just started running too.

National correspondent Alex Wagner remembers the thunder of fighter jets flying low over Manhattan, wondering whether the city was still under aerial attack, and being aware of “walking around a grave site, breathing in the dust of smoking bones every day. That part was really fucking dark.” “There were tanks across Houston. It was crazy, for a long time," says the drummer for the Rapture. But, as Wagner notes, “There was also this pronounced sense of individual destiny-making.” Artists rededicated themselves to the only thing they had any control over, their work.

Nick Valensi, the Strokes:

That evening, that night, after shit had kind of died down, we all met up. I remember we were all talking on the phone, “What are we going to do, what are we doing? Let’s go to the studio, to the rehearsal room.”

September 11, 2001 was the vinyl release date of the Strokes’ debut album. Is This It finally came out on disc in America in October. For Halloween, the band played a now-legendary show at Hammerstein, six weeks after 9/11. The city still smelled like barbecue and burning metal. The nervous carnival atmosphere is palpable on film - “a little Saturnalia after a long couple weeks of the city belching smoke and planes flying into things. There were still missing-person signs everywhere,” recalls one journalist. People were looking for a nocturnal escape from gazing at ash and ruins all day. They found it indoors, in clubs. Many of them fled across the river, to Brooklyn.

That fall I felt like no one really knew how to fully process what was happening and as a result everyone kind of went bonkers crazy. I don’t know whether it was a result of the tragedy, I just remember that’s when a lot of the craziest parties started. And that’s when I moved to Brooklyn and immediately was exposed to all this new stuff.

—Ed Droste, Grizzly Bear

There was a silver lining to the clouds of smoke.

It was an incredibly horrible event, right? That’s established. But it was also very inspirational. When something like that happens, on your doorstep, and you’re there, it becomes the center of the world, and you feel like you’re in the center of the world. That’s inspiration in itself. It made you want to pick up your pen and write something down.

—Angus Andrew, the Liars

Fatalism followed in the wake of the great memento mori. People embraced hedonism and clung to art. The nervous energy of the city fused with the sound of music, its “guitars apparently tuned to the frequency of New York power lines,” in the memorable words of Mahajan’s NYRB review. Something happened; New York City became the center of the world again. And the Strokes became an international symbol for New York in the same way the mayor did, overnight.

Dave Gottlieb of RCA:

September 11 did affect all this greatly. I mean, for Is This It to come out literally two weeks later? It made it hard for all the people that wanted to be cynical about the Strokes or take shots at them. Instead it became about, “All right, this is an underdog.” September 11 made Yeah Yeah Yeahs and the Strokes and Interpol, it made them all underdogs because they became representative of something larger.

Dean Wareham, of Luna:

I would get on the phone and people would ask, “What do you think about Osama bin Laden? What do you think about the Strokes?” These were the two things that were going on in my town.

Kimya Dawson, of the Moldy Peaches:

The Strokes became the ambassadors, the embodiment of that leather jacket, denim, sunglasses cool New York City in people’s minds. “That’s New York City music. They’re the new Velvet Underground.”

Kimya Dawson also recalls Winona Ryder and Courtney Love beckoning her friend Julian Casablancas to “come be famous with us, don’t hang out with them” around this time, and Casablancas being uncomfortable with sudden celebrity.

Within a year, the Strokes were performing live on MTV and playing Radio City Music Hall with the White Stripes; Beck showed up. Several members would be groomed by Courtney Love. Along with many other bands for whom they opened the door, they were courted in the music industry’s last over-hyped feeding frenzy before Napster took over. “In a weird way, they were like a boy band,” says one record company manager, supplemented by a montage of Strokes lookalikes in the film, dark-mirror images of the Back Street Boys and NSYNC. In place of cargo shorts or jumpsuits, they donned dinner jackets and skinny jeans, the international uniform of the millennial hipster.

And, “the artists and musicians moved in droves out of Manhattan into Williamsburg,” where “the rent was so cheap you could afford to take risks.” Abandoned buildings became rehearsal spaces and studios. A parking lot under the Williamsburg Bridge became an impromptu stage in 2002, with crowded faces peering from the rooftops in an inversion of the Beatles’ last stand.

Even on the day of the attacks, however, there was a hint of things to come, according to one member of TV on the Radio, Tunde Adembimpe:

We all walked down onto Grand Street in Williamsburg. We all stop there and we’re just staring at [the towers] when this guy walked by us. If this were a movie, that guy would be foreshadowing the next fifteen years. We’re all staring at this building, freaked out, just really freaked out, wondering what’s happening, and this guy comes and stops next to us. He’s got a briefcase and a tie. He’s a little bit older than us, and he’s like, “Oh my God. A lot of clients of mine were in that building. I probably just lost a lot of clients.”

After restraining Dave Sitek from attacking the callous gawker, Adembimpe continues:

That guy in the suit? He was the canary in the fucking coal mine. I feel like New York was about to turn into what it is now way earlier, and then 9/11 paused it.

RZA seems to agree:

I feel like 9/11 froze our city. It definitely froze me. It numbed us, but at the same time it numbed those who were successful, but those who were striving to come on, it inspired them. That’s usually a paradox; you’ll see one thing stop and then something else grows.

In the ten-year spotlit reprieve, a tree grew in Brooklyn. Something flowered, was harvested, and exported to the world. Some of it was skinny jeans. In 2013, the year that Foxygen advised assholes to relax, “you’re not in Brooklyn anymore,” Mayor Bloomberg announced the approval of a new waterfront development for Brooklyn Bridge Park. The borough was well on its way to becoming “That guy in the suit” that TV on the Radio witnessed in Williamsburg on September 11, 2001.

Only, he was now wearing a dinner jacket and tight pants.