Syncretism is the religious equivalent of what Neapolitans call pezzotto - a bricolage of diverse materials.

You could also think of syncretism as the religious equivalent of what archeologists and architectural historians call spolia: incorporating old materials such as funerary reliefs into new constructions for decorative or symbolic purposes.

Syncretism, the fusion of elements from different religions, is one of the quirkier aspects of cultural evolution. In pantheistic cultures like ancient Rome, with an endless supply of domestic gods and demigods exposed to new deities through trade and conquest, it was routine to merge one divinity with another - by adopting new names or combining the two.

Thus a Greek god was combined with an Egyptian one, Zeus with Ammon-Re, given a pair of horns, and venerated as Zeus-Ammon in Pompeii.

Secular society is equally susceptible to combining disparate belief systems, or supplanting old spiritual practices with new ones, in the guise of art or even (especially) science.

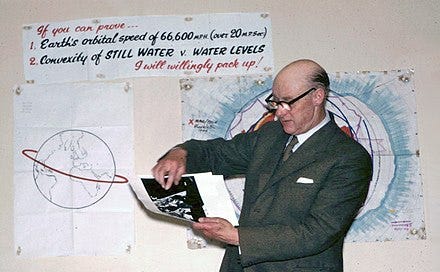

Isaac Newton formulated the mathematical Principia of physics, but he also studied alchemy, followed Rosicrucianism, and believed he had a prophetic ability to forensically interpret the Bible.

Today we associate the philosopher Pythagoras with trigonometry, astronomy and musical theory, but the Greek who established the Pythagorean theorem and the 12-tone harmonic scale also believed we shouldn’t eat beans, lest we accidentally consume our reincarnated grandmothers. Along with another pre-Socratic philosopher, Empedocles, Pythagoras and his followers practiced a mystery religion, Orphism.

According to the mathematician and logician Bertrand Russel,

The Orphics were an ascetic sect; wine, to them, was only a symbol, as, later, in the Christian sacrament. The intoxication that they sought was that of "enthusiasm," of union with the god. They believed themselves, in this way, to acquire mystic knowledge not obtainable by ordinary means. This mystical element entered into Greek philosophy with Pythagoras, who was a reformer of Orphism as Orpheus was a reformer of the religion of Dionysus. From Pythagoras Orphic elements entered into the philosophy of Plato, and from Plato into most later philosophy that was in any degree religious.

—The History of Western Philosophy (1947)

According to mythographer Peter Kingsley, the ideas of Pythagoras and Empedocles also trickled into southern Egypt and Islam, informing Sufism (along with alchemy and medieval mysticism).

Plato’s doctrine of Ideal forms existing beyond the realm of physics was particularly compatible with Christianity. Likewise, the theogony of Dionysus established the separation between body and soul.

Whatever the order of influence, from Dionysus and Orpheus to Pythagoras and Empedocles (and Plato, et al), the common mythical theme was katabasis: all these figures were said to have descended to the underworld and returned, underscoring a universal human desire to transcend death, so prevalent in fertility and mystery cults. In Sicily, the terrain of Empedocles and Pythagoras, the underworld involved fire and volcanoes, which later informed Christian concepts of hell.

Outside of early science, or natural philosophy (already linked with music, through the figures of Pythagoras and Orpheus) - in the field of art, religious syncretism is rampant. One need only visit the Vatican museum, Sistine Chapel, Apostolic Palace, Farnese collection in Naples, or a cathedral to see how Greco-Roman and Near Eastern mythology coexist with Christian iconography.

Mariology, or veneration of the Virgin Mary, was a choice substitute for the cults of previous virgin goddesses, and was in turn supplanted by the secular idolization of chaste women in the songs of Courtly Love.

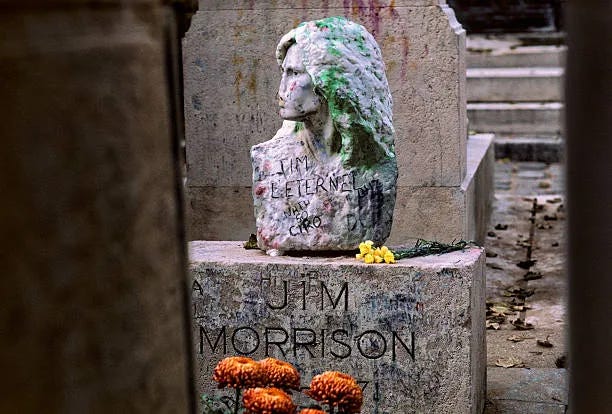

In Romantic literature, the life and death masks, and locks of hair belonging to English poets collected in the Keats-Shelley Museum, and the non-Catholic cemetery in Rome where these poets are buried, can only be described as secular relics and pilgrimage sites.

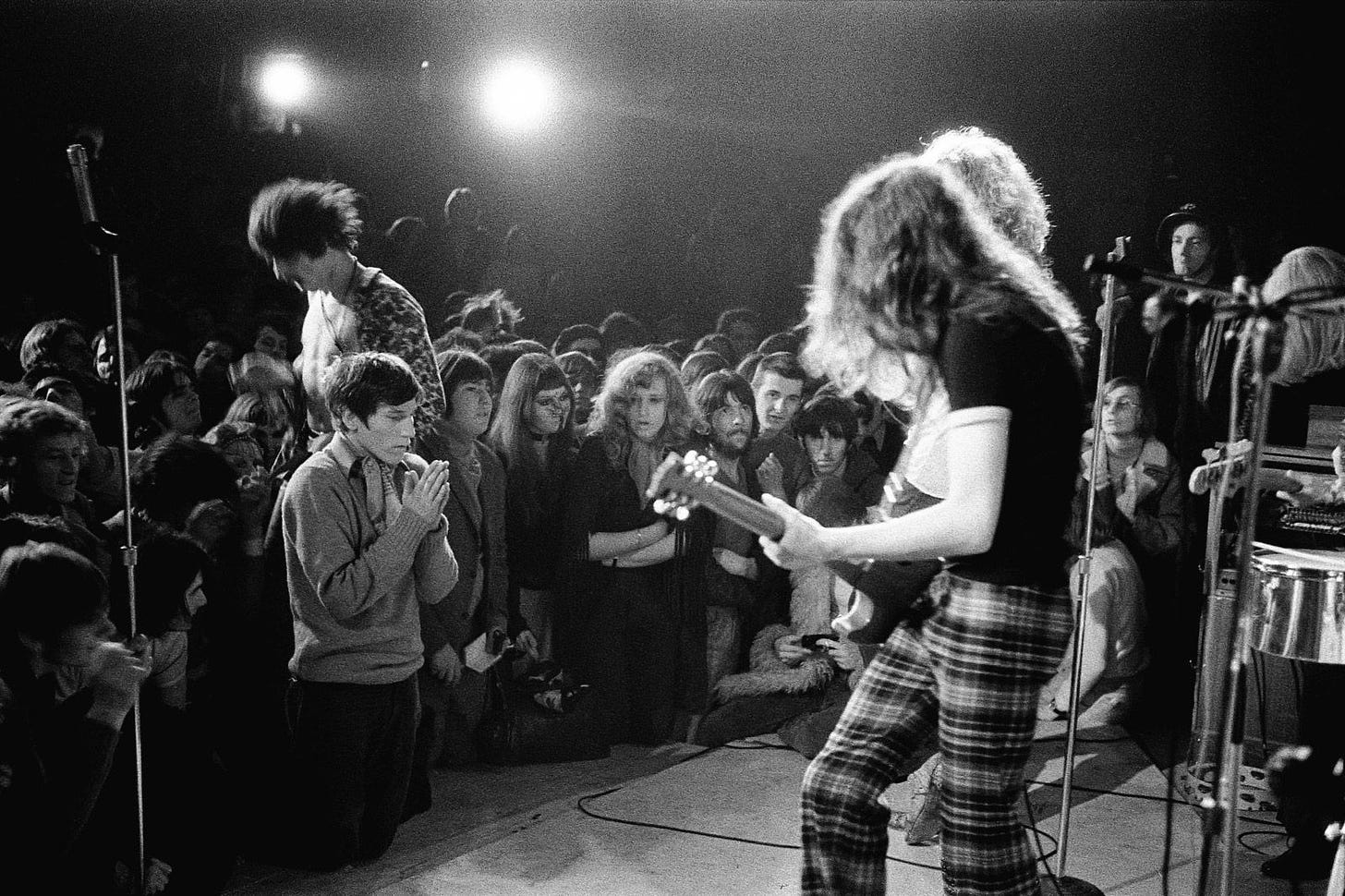

150 years after the deaths of Keats and Shelley, there’s this bloke.

And this one.

Syncretism becomes more covert, and interesting, in monotheistic religions reluctant, or hostile, towards polytheism and false idols. Even in this context, old symbols of veneration are remarkably persistent and adaptable - from the standpoint of orthodoxy, Islam and the Byzantine church were prescient in their iconoclasm, forbidding the depiction of such imagery lest it be misused. Though monotheistic, Roman Catholicism, assisted by art, provided opportunities for something like polytheism to persist within the church (to say nothing of what’s around the edges and outside of official church doctrine). The twelve apostles happily matched the Olympic pantheon in number, and gladly assumed their places in the alcoves of the Pantheon in Rome. With plenty of saints to follow, along with the Madonna, Catholicism proved uniquely open to syncretism with other religions. Thus did the animistic spirits of West African diaspora religion become equated with Roman Catholic saints in, for example, Haitian vodoun. Or for that matter, with the Protestant devil in blues and rock & roll. Pentecostalism (“primitive Pentecostalism”), an ecstatic form of Protestantism and one of the cradles of American popular music, was equally conducive to practices that wouldn’t have seemed out of place in the Temple of Apollo or the Oracle of Cuma, such as snake handling and speaking in tongues.

The following are a few cases of spiritual symbiosis in Italy - leaving museums out of the equation, for now. These are examples one can find inside, or on the facade of, a church.

Pigna di San Pietro

An enormous pinecone flanked by emperor Hadrian’s peacocks once stood near the Pantheon, next to the Temple of Isis. Now it’s next to St. Peter’s Basilica, decorated with a quotation from Dante’s Inferno, comparing the pinecone to the size of King Nimrod’s face. Pinecones were associated with Bacchus, found on the tip of his thyrsus (a scepter symbolizing Dionysus and fertility).

Cathedra di San Pietro

More enormous still, the seat of St. Peter is enthroned beneath a canopy of brass pilfered from the Pantheon.

Santa Maria Sopre Minerva

The Roman Pantheon is now a church, the Basilica of Saint Mary and the Martyrs. As is the Santa Maria sopre Minerva, or Saint Mary’s over Minerva. The church of the Virgin rests atop the temple of Roman Minerva - the Greek virgin, Athena.

Temple of Vesta

Outside Rome, the Temple of Vesta was once inhabited by Vestal Virgins. Later it was inhabited by Roman Catholic nuns. The ruins stand next to a nineteenth-century restaurant named after another virgin priestess, La Sibilla.

Moses, San Pietro in Vincoli

Inside the church colloquially known as “Little Saint Peter’s” (far less crowded than Peter’s basilica in Vatican City), sits a statue of Moses by Michelangelo, part of the tomb of Julius II. The sculptor complained he wasted the last years of his youth on this statue, completing it on the cusp of his forties. “I should’ve made matches instead,” he regretted.

His Hebrew prophet has horns. This is a common element in Christian iconography of Moses; there are numerous explanations for how this came to be, ranging from St. Jerome’s mistranslation of Exodus to anti-semitism, or the artist’s intention to produce an optical illusion. The horns supposedly represent beams of enlightenment following Moses’ reception of the Ten Commandments. Yet the rest of this sculpture positively radiates light and energy, compared to those floppy, nubbin horns. Surely Michelangelo could’ve rendered more energetic rays of light.

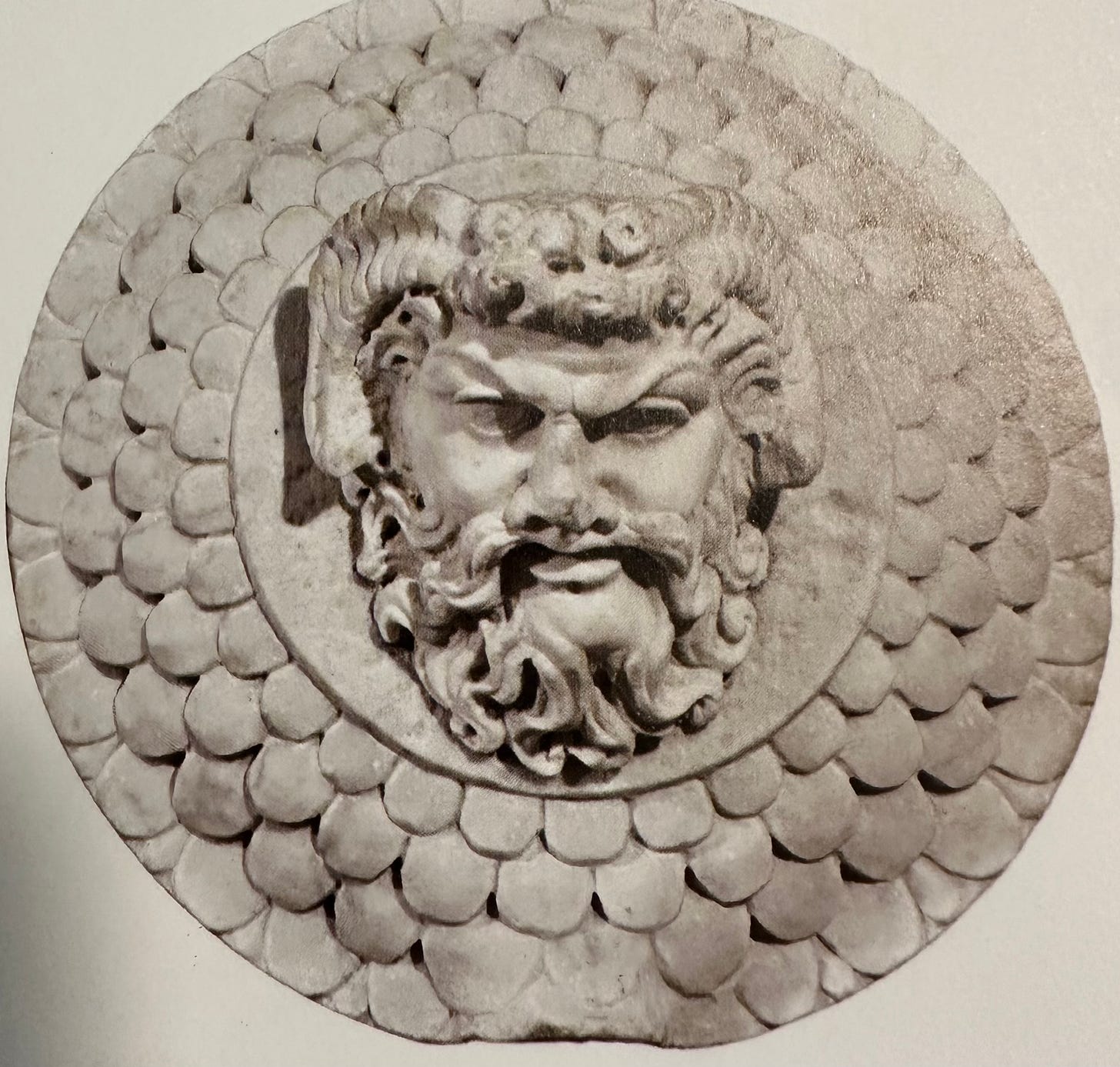

Considering Moses was sculpted by the man who decorated the Sistine Chapel with pagan Sibyls, that he was in a bad mood by the time it was finished, and his marble depicts Moses at the moment he’s descended Mount Sinai to discover the Israelites worshipping a Golden Calf… it’s tempting to call (pardon my Italian) cavolata on the beams of light theory (“bullshit”). (Note the grotesque face on the slab behind the top of Moses’ head; it could easily accommodate the horns of Pan or Zeus-Ammon.)

Nonetheless, Michelangelo’s Moses sits over the bones of a pope, next to the prison chains of St. Peter.

Basilica di San Clemente, the Mithraeum

This sacrificial altar, dedicated to the cult deity Mithras, is the centerpiece in a feasting and devotional chamber known as a Mithraeum. It was concealed beneath not one but two Christian churches, until excavations began in the nineteenth century. Above it lies the 4th c. Basilica of San Clemente.

Above that, the 12th c. San Clemente, where church services take place today.

Syncretism between the followers of Mithras and Christ may be an illusion here, the result of coincidence and archeology - there were hundreds of Mithraeums in Rome in the 2nd c. AD, when the one below the two levels of San Clemente was still in use. On the other hand, there are many congruities in the stories of these figures.

Syncretism is opportunistic, often dubious and conjectural - especially when saints and relics are involved. The relics of St. Clement are said to be housed upstairs; they’re also claimed by a church in Kiev, and other reliquaries on the Black Sea. No one’s even sure who St. Clement, the fourth Pope, was - a contemporary of Peter and Paul, or a Jewish ex-slave who belonged to the household of a man named Clemens, the martyred cousin of emperor Domitian.

I’ll make a few conjectures of my own, about syncretism in San Clemente.

This funerary epitaph in the 4th c. San Clemente, on the second level downstairs, is undeniably syncretic - though it may simply reflect the resourceful use of materials. The older side, with stately capital lettering, was used for a pagan epitaph; the side with irregular, rustic symbols is an inscription for a Christian burial.

In apocryphal legend, San Clemente was exiled by the emperor Trajan (98-117) to the Crimea, to work in the mines. His missionary zeal among fellow prisoners - and, we’re told, Roman soldiers - was so infectious that the Roman command martyred him. Mithras, incidentally, was mostly venerated by Roman soldiers. Where the devotees of Dionysus or Isis were traditionally women, the Roman cult of Mithras was strictly men.

Mithras originally derives from pre-Zoroastrian Iran. Before the religious reformer Zoroaster (6th c. BC), Iranian religion was polytheistic. Mithras was the supreme demigod, aligned with Sol, the Sun - his representative on earth. The Greeks and Romans interpreted Mithras as the Sun himself - the deity most ripe for monotheism, if comparative religion is any indication.

In myth, Mithras is a mediator between heaven and earth. The Sun god, through a messenger Raven, commands him to sacrifice a white bull. He does so reluctantly, ushering the world into creation in a sequence reminiscent of Genesis. At the end of the sequence, beginning with the firmament and waters and ending with plants and animals, lesser creatures emerge from underground - a serpent and scorpion, a dog, representing the beginning of good and evil and the human condition.

Following his creative sacrifice, Mithras and the Sun feast together, eat bread, and drink wine. Mithras ascends to the chariot of the Sun, carried aloft through the sky. One Mithraic hymn begins, “Thou hast redeemed us too by shedding the eteral blood.”

The structural similarities between Christian and Persian doctrine suggest one reason Mithras was a threat to early Christianity. He was also the guiding light and god of social contracts, something like a covenant. On top of that, Mithraism was the cult of governors and Roman soldiers, the very persecutors of the Christians. While Greeks disavowed Mithras because the Persians were, historically, their sworn enemies, the Romans adopted him enthusiastically, in a distinctly-Roman fashion that bore little resemblance to Iran’s. In the 2nd century, a reformed version of Mithraism became popular in Rome, while Christianity was struggling to take root. Romans connected Mithraism with the philosophy of Plato (in part because they worshipped him in caves, like the famous allegory of the cave in Plato’s Republic), as Christian scholars later tied their own theology to Plato. After the conversion of Emperor Constantine in the Eastern Empire, Mithraism quickly disappeared. But not before a struggle between the new state religion in Greek Constantinople, Christianity, and older pagan religion in Rome, in the 4th century AD.

The frescoes in the 4th c. Basilica of San Clemente are distinctly Eastern, what we now call Byzantine or Greek Orthodox.

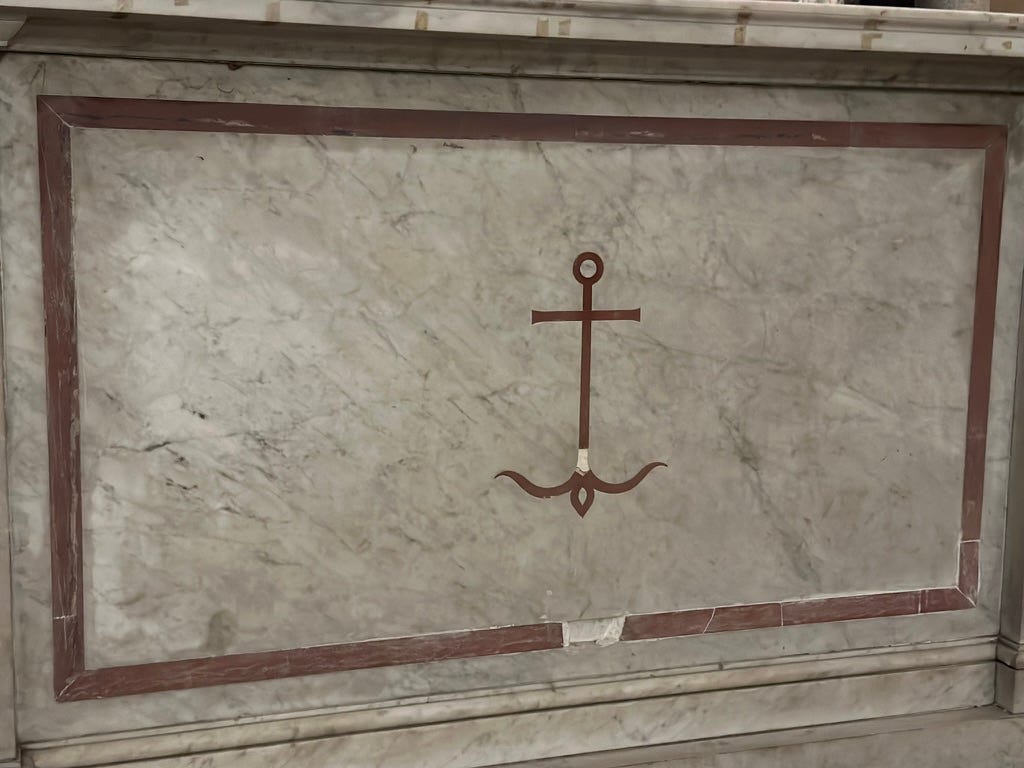

St. Clement died in the Byzantine East, near the border zone where Persian Zoroastrianism first permeated Rome. He was martyred by being tied to an anchor and thrown into the Black Sea. His symbol, seen here on a much newer addition to the Basilica of San Clemente, is the Anchorite Cross. Coincidentally (or not), it looks a lot like a Greek Cross lording it over - or combined with - a bull’s skull and horns.

Numerous symbolic and chronological coincidences exist between the proliferation of these two Eastern cults, Christianity and Mithraism in Rome, in the basements of San Clemente. It may be pure happenstance that an early Christian basilica was constructed over a pagan Roman altar, originally - Mithraeums, like many early-Christian devotional spaces, were always subterranean. However this is also a common maneuver, an effective way of acclimating the adherents of an old religion to a new faith, like the church of Santa Maria sopre Minerva or the Pantheon: highlighting the similarities between two sacred figures by venerating them on the same ground. A syncretic interpretation seems to be encouraged here as well, curated by the exhibition of modern archeology and legendary history beneath San Clemente.

San Genarro

Outside of Naples, in Pozzuoli, a modest chapel is home to a curious form of worship that’s not exactly pagan, but not entirely Catholic. It certainly leaves the door open for non-traditional worship. There are dogs among the pews. Guitar melodies. The stone on which Genarro was beheaded by Romans in a nearby volcano is housed in an alcove. Each year, a sisterhood of nuns claiming to share a bloodline with the saint awaits an annual miracle unrecognized by the Catholic church: the liquefaction of San Genarro’s blood, contained here in a vial. They begin by reciting prayers and oaths, but if the blood fails to liquefy, the sisters proceed to cursing. The last time the blood failed to run, the curses flew, and the failed miracle was blamed for a local earthquake.

(There’s also profanity frescoed on the walls of San Clemente, one of the earliest examples of Italian vernacular in writing: the words of a Roman nobleman cursing his servants as “sons of harlots” after they fail to arrest St. Clement.)

Assisi

Like San Clemente, the hometown of St. Francis is the setting where two outsider cults infiltrated mainstream religion - the religion of Rome, then Roman Catholicism. The first outsider faith was the Christianity of San Rufino, a bishop from Turkey in the 3rd c. AD. When he came to preach to Romans in Assisi, he was martyred (238 AD). His sarcophagus remains in the crypt of the Cathedral of San Rufino, decorated with scenes from Greek mythology similar to Christian iconography: the story of a shepherd, Endymion, and the moon goddess Selene, replete with winged gods and cherubic cupids, as well as Tellus, the god of fertility, with his horn of plenty.

The cathedral contains the remnants of another sarcophagus, from the early 2nd c. AD, displaying a Greek libation ceremony that involves spilling sacrificial wine on an altar.

St. Francis prayed before the sarcophagus of San Rufino in the 12th century, almost ten centuries after he was martyred, in the same church where the younger saint was baptized.

The cathedral is built over the old Roman forum, above a pagan temple dedicated to the Bona Mater, Roman goddess of nature and fertility. A mix of pagan and Christian iconography is evident throughout the building.

The second outsider religion that syncretized with mainstream faith in Assisi was a cult of asceticism, which the popularity of St. Francis compelled the Vatican to incorporate.

After San Rufino tried to bring Christianity to Assisi from Turkey, at some point in the intervening years, a Christian cult of hermitage also arrived from abroad, from Egypt or the East. Hermitage has its roots in the primitive Desert Fathers (from Greek eremos, or “desert”) - early Christian monastics who withdrew to the deserts of Egypt or Syria to fast and meditate. A similar practice was established in Assisi by Francis’ day; the fledgling saint retired to a grotto on Mount Subasio after renouncing his father’s wealth, meditating in the wilderness like others. Throughout his life, Francis returned to Subasio with his followers, living in a cave and sleeping in a nest, in what is known as the Eremos delle Carceri, a primitive “Hermitage of Cells,” expanded into a small monastery in the years since.

In a way, Francis had already been influenced by the East in his youth. Before he sang the praises of “Lady Poverty,” he sang troubadour songs. Think of the early Saint as a medieval Italian version of the Strokes - his father was a wealthy fashionista who sold the bright fine silks his son liked to wear as he extolled his love of vernacular song. His mother was likely from Provence, and his father nicknamed him Francesco, or “Frenchman.” The Provençal songs of France, like the desert hermits, derived from the territories which by St. Francis’ time were part of the world of Islam. Later in life, the friar visited these lands seeking to calm the crusades, even preaching to an appreciative Sultan of Egypt, the nephew of Saladin.

When Francis gave up his fine clothes and renounced familial wealth to become an itinerant street preacher, he was deemed insane. However his message became popular enough that Pope Nicholas III was forced to incorporate the Brothers Minor into the Catholic church; the potentially-subversive Franciscan order was officially recognized in 1210. Today its founder is one of the few saints recognized by Protestants, and respected by Muslims. The patron saint of Italy, animals, nature, and ecology, or earth science.

St. Francis said he wanted to be buried “in a simple cave.” The church ensured his remains and relics were buried inside the Basilica of Saint Francis instead, the “World Headquarters of Peace.”

A large cathedral adorned with frescoes by the genus of Renaissance painting, Giotto within, and pagan grotesques without.

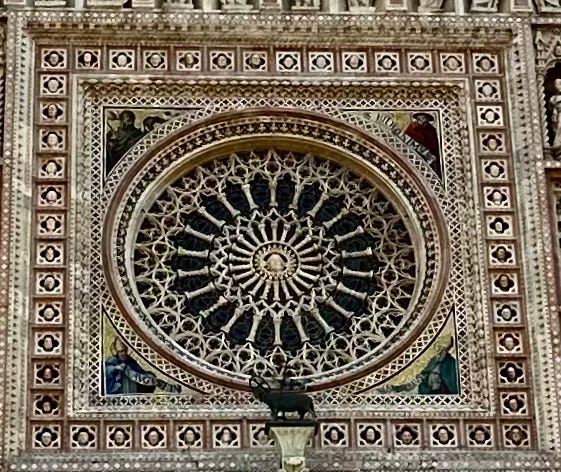

Duomo di Orvieto (Cattedrale di Santa Maria Assunta)

To be clear, it’s often uncertain to what extent a piece of religious symbolism, art or decor is intentionally syncretic, and to what degree it’s simply part of a shared cultural vocabulary, such as architecture or literary convention. Or the result of convenience and opportunity. It’s part of what allows seemingly outrageous forms of syncretism to transpire so subtly, until they don’t - before it was overthrown the Duvalier government in Haiti, for example, which terrorized its citizens through voodoo superstitions and zombie pharmacology, was officially Roman Catholic.

The last example on the list feels fairly intentional. Though one wonders to what extent the artist appreciated the fact he was venerating vernacular and pagan poets and philosophers on the walls of the Orvieto Cathedral (or perhaps I’ve failed to appreciate the extent to which religious art is really popular and secular).

The cathedral outside is a synthesis of Moorish stripes from the south and Gothic arches from the north, dotted with a winged bull and eagle, and the same Mystic Rose that prefaces Madonna-centric churches in Assisi and elsewhere - here the Rose suggests the Virgin’s womb, given that this stained-glass window encircles an image of her son’s face.

The piers on the facade have bas-reliefs from the school of Maitani, depicting scenes from Genesis using a grotesque design that inspired the word vignette (little scenes from “the vine”). An early comic strip.

But what’s most interesting is inside. In the Chapel of the Madonna (di San Brizio), Luca Signorelli completed the work begun by Fra Angelico, and inspired Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel with his depiction of the Last Judgement. This is what draws art aficionados into the room.

I was more impressed by the subjects of the frescoes below Signorelli’s ceiling, which were probably painted by the master’s apprentices. Pagan poets and philosophers, vernacular Italians, and grotesques painted around the year 1500, just after the discovery of “the grotesque” in Nero’s Domus Aurea.

This gentleman is Ovid, whose poetry was too risqué even for the first emperor of Rome (Augustus banished him to the Black Sea, as Trajan would San Clemente). Later Ovid was bowdlerized into Renaissance respectability.

Empedocles, the Orphic philosopher whose ideas about love and hate were seen as compatible with Christianity, by Signorelli.

And of course, among many others, Dante (left).

The poet who conceptualized Purgatorio in Italian, persuading the Latin-speaking church to adopt purgatory as official doctrine (a lucrative one). He also psychoanalyzed sin through the voice of his characters in limbo, in a turn towards human psychology. As St. Augustine’s essays made the concept of original sin synonymous with Catholicism and Calvinism, and Milton’s Paradise Lost recast Satan as a Promethean genius to be emulated by protestant Romantics (and rock stars) to come, Dante rewrote the church’s concept of the afterlife. Suggesting that one Romantic buried in Rome, Percy B. Shelley, was onto something when he wrote In Defense of Poetry:

Poets are the unacknowledged legislators of the world.

As we’ll see in next week’s reliquary, a little literary-spiritual syncretism goes a long way.