Two weeks ago I coined a phrase to describe art and history: grotto pezzotto.

Basically, it means that storytelling, artistic representation, state and religious symbolism, and history itself, are woven together from existing strands of narrative material. The rest of those historical threads remain buried or obscured—sometimes on purpose.

Take the history of Nero, last emperor of the Julio-Claudian dynasty. His successors condemned his memory by law. Proclaimed him damnatio memoriae, a “damned memory.” Emperor Trajan covered much of Nero’s 200,000-acre palace with dirt. Another emperor, Vespasian, landfilled his artificial lake to create the floor of the Flavian Amphitheater, better known as the Colosseum.

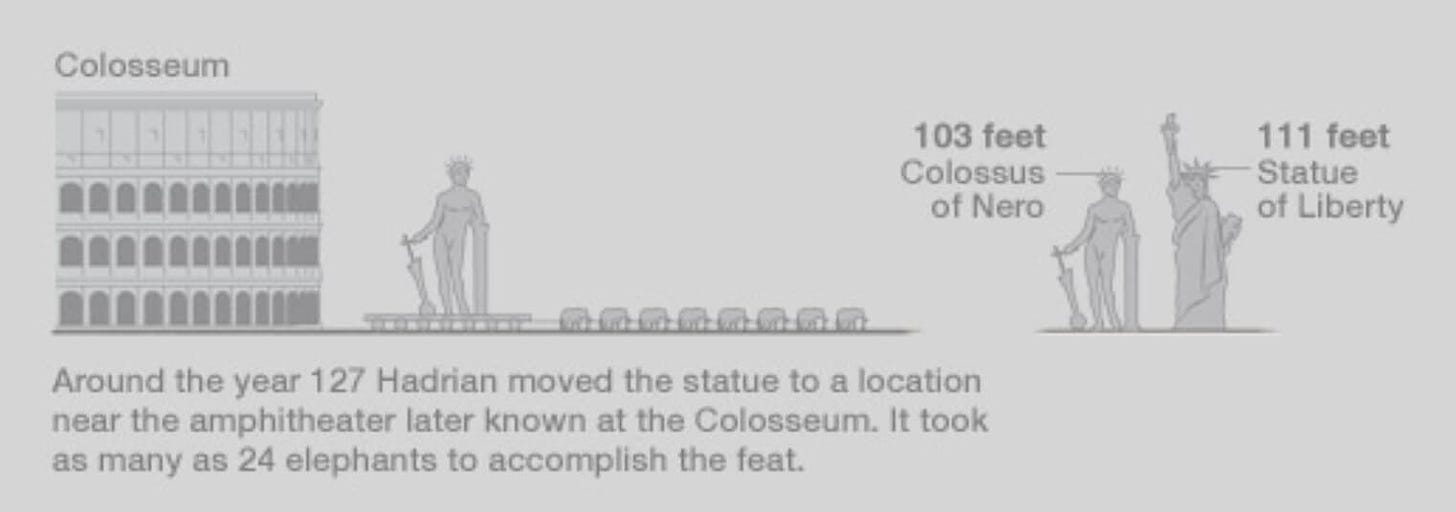

It’s called the Colosseum, as opposed to the Flavian Amphitheater, by the world outside of Rome, because it was fronted by a Colossus. Similar to the giant Wonder of the Ancient World, the Colossus of Rhodes - an enormous bronze statue of Apollo, the Sun.

The one relic Nero’s successors preserved of his “damned memory” was a gargantuan bronze sculpture in his image, which came from his palace. The memento was just too damned Colossal. So Vespasian crowned it with sunbeams and called Nero the god of light. (Others say Nero modeled himself after Apollo to begin with, and gave himself the solar crown.)

After Vespasian, Hadrian placed the Colossus of Apollo-Nero in front of Rome’s public amphitheater for all to admire, as a deity. Funny way to condemn someone to obscurity, placing them in the plain light of the Sun.

The Colossus is long gone, made of precious metal. The Goths probably pilfered most of the bronze, and Pope Gregory turned what was left into cannons. All that remained were pieces of the base, which even Mussolini tried to hide.

If you read between the lines, the building now synonymous with Rome, and Western civilization itself (“when the Colosseum falls…Rome…the World”), is named after a statue of a damned madman who was meant to be forgotten.

We can see this process of confused historical revisionism taking place between the eighth and nineteenth centuries, in Byron’s misquotation of the Anglo-Saxon historian Bede. From the “Colossus” of Nero, to the “Colosseum” of Rome.

As long as the Colossus stands, Rome will stand,

when the Colossus falls, Rome will fall,

when Rome falls, so falls the world.

—the Venerable Bede (672 - 735 AD)

While stands the Colosseum, Rome shall stand;

When falls the Colosseum, Rome shall fall;

And when Rome falls—the World.

—Lord Byron, Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage (1818)

Trajan’s Column, a tourist site nearly on par with the Colosseum, dedicated to the emperor who buried Nero’s palace to build his public baths, is exactly as tall as the dirt was deep over Nero’s palace when Trajan entombed it.

The height of the column is a monument to atonement as much as Emperor Trajan, determined by a desire to appease Roman superstitions about moving the earth around Nero’s palace, and upsetting the gods below.

Little, if anything, in the history of art, culture, and religion is entirely new or original, or stands on its own, and that includes my new phrase, grotto pezzotto. Like whoever attached Apollo’s crown to the head of Nero and renamed him the Sun, I’ve merely stitched two words together in Italian, to form something useful to a narrative.

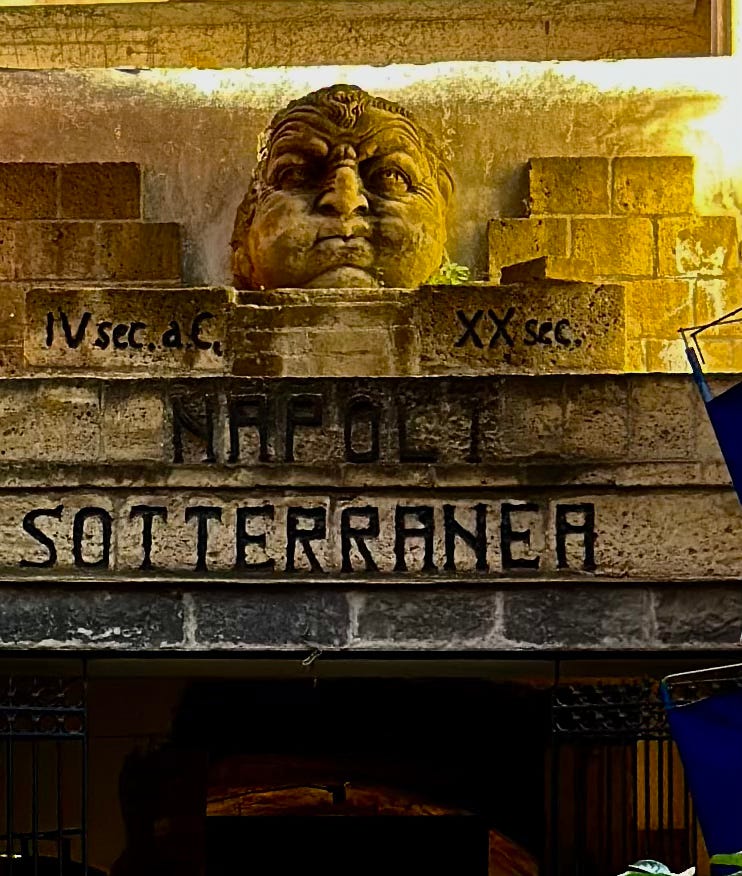

Grotto (underground, like a “cave”) and pezzotto (unoriginal; artificially pieced-together from pre-existing parts; fake).

Speaking of grotto pezzotto, or constructing narratives with hidden meanings, it’s time to talk about the history of the grotesque.

I’ve already told pieces of this story elsewhere, in the vein of Humor. But it bears repeating from a different perspective. From the bottom of Nero’s Domus Aurea, or House of Gold.

One of the deepest stories ever told, I think. Part of the reason I came to Rome, and bent over backwards to get inside the Domus Aurea. (It wasn’t easy, guide services are flakey, excavations stop and start, and tours are frequently cancelled due to atmosphere and safety conditions; mine was rescheduled for a private party in the emperor’s house.)

I came to to see if the story was true.

The history of the word “grotesque,” inside the Emperor’s House of Gold.

In the beginning, there was the word: “Grotesque.”

He who would know the history of words, should know the history of everything.

—Will Durant

I often find this to be true. No one knows the history of everything, but words are a good start. The story behind a word is like the story behind a statue; you never know exactly what you’re looking at on the surface.

Today, grotesque means repulsive, distorted, ugly, monstrous. Like a gargoyle.

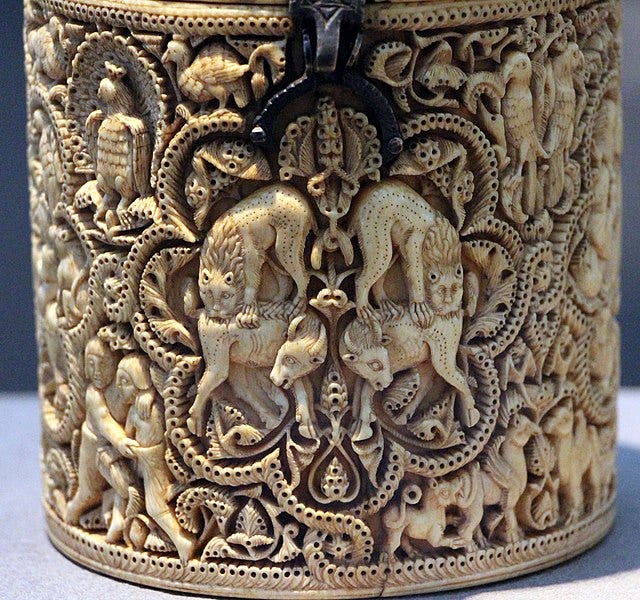

If you’re familiar with Edgar Allan Poe or Southern Gothic literature, you might associate it with horror. Flannery O’Connor penned a treatise on “Some Aspects of the Grotesque in Southern Fiction” (1960), and Poe published a short-story collection called Tales of the Grotesque and Arabesque (1840), suggesting a connection between the grotesque and Eastern exoticism.

Indeed, it’s feasible that the recurring design pattern now known as a grotesque - like the dome in Roman architecture, or troubadour love songs in France - may have been informed by innovations in the Near and Middle East, in the form of arabesques.

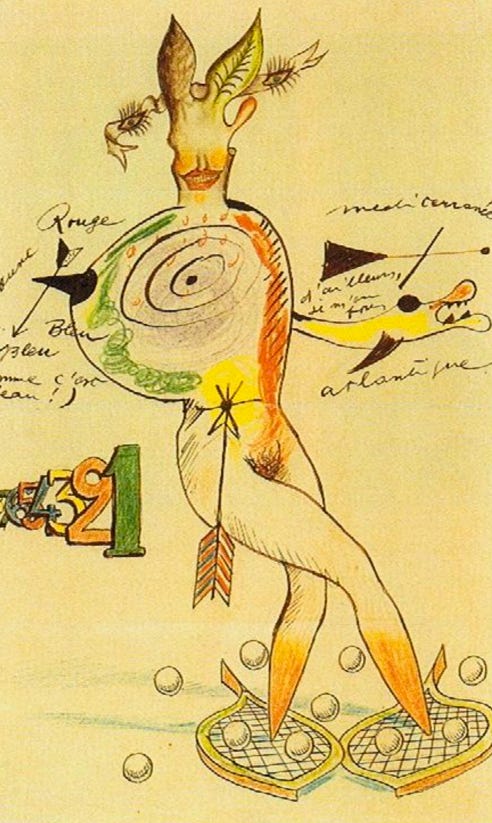

If you’re familiar with the modernist parlor game known as “Exquisite Corpse”—you probably have children. You also probably realize there’s a comic aspect to the grotesque. It’s been linked to satire and caricature, inspiring both sympathy and disgust.

In the game, one person draws a head on a sheet of paper, folded into three sections. The second draws a torso, the third the legs. Each illustrator is only allowed to see the segment they’re working on, until the sheet is unfolded at the end. To reveal a hybrid creature, stitched together from the imaginations of three different people, ideally with different levels of psychological maturity. The results are often hilarious. Perhaps a little disturbing.

That’s about as good a definition of “the grotesque” as I can give, an Exquisite Corpse.

A hybrid form. By definition, a “monster.” A mythical combination of parts, transgressing the bounds of what’s considered categorically natural. The duckbill platypus of art and literature.

This is part of the reason a genre of nineteenth-century American theater infamous for transgressing racial boundaries has been referred to as “grotesque caricature,” or simply “grotesque racism.” A form of so-called “musical comedy” - blackface minstrelsy. Because it’s a repulsive distortion, or caricature, but also because it suggests crossing boundaries. This sort of racial transgression, while often buried and repressed, is rampant in Southern Gothic literature - particularly in the racial anxieties of Flannery O’Conner and E. A. Poe.

Feeling funny? Perhaps a little disturbed? This is merely one, peculiarly-American form of the grotesque.

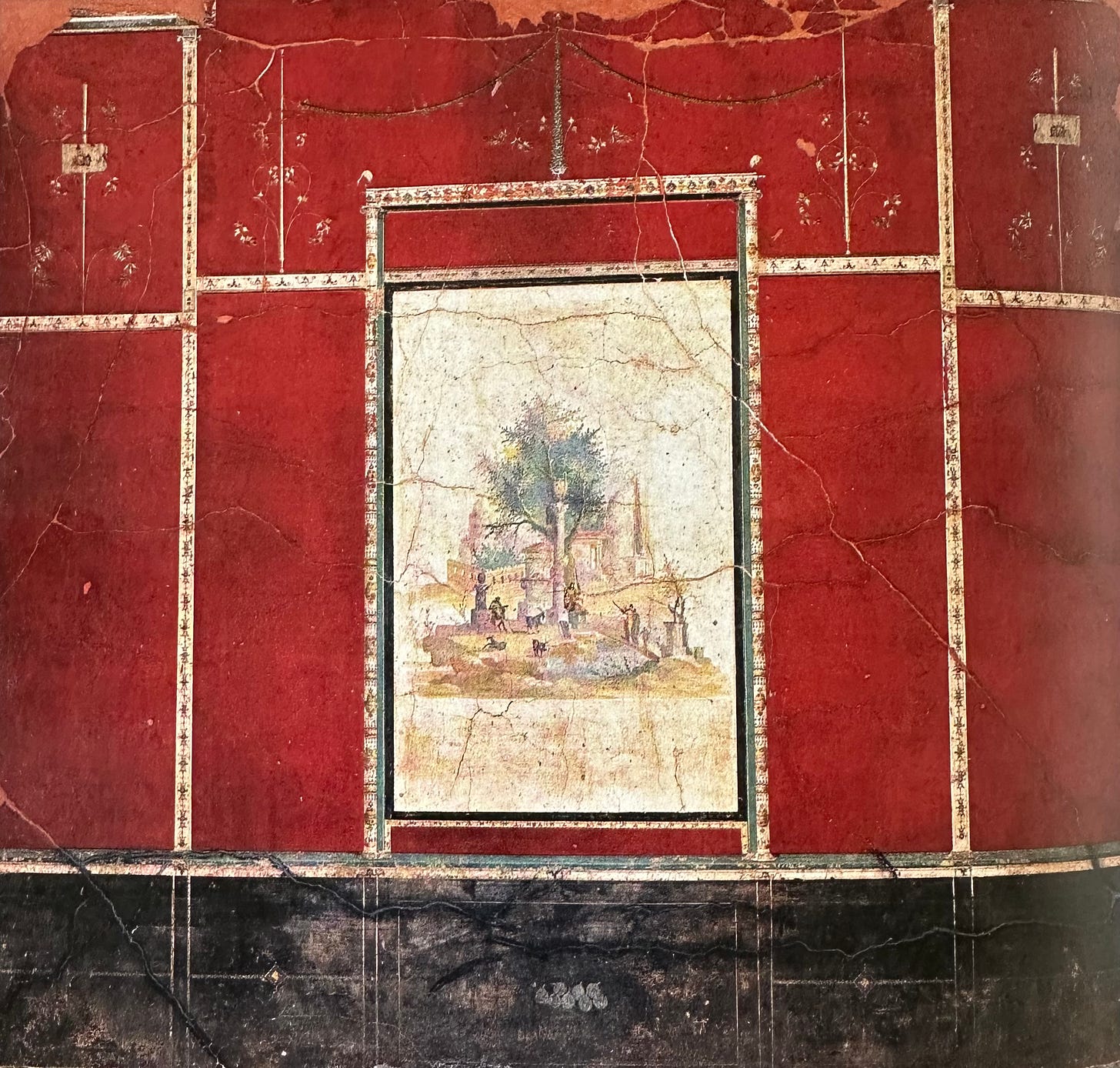

In Roman art and decorative motifs, grotesque patterns aren’t so much disturbing as whimsical. Here’s one of the first such patterns in art history to be given the name “grotesque.”

Hardly repulsive. Maybe it reminds you of grandma’s wallpaper. If you look closely, there are hybrid, mythical creatures around the edges: a griffin or sphinx, some sort of bipedal bear or canine, a fairy-like child with wings made of flowers or seeds, combined with other biomorphic patterns - cute little monsters. A mixture of human, animal, and plant forms.

What’s this have to do with repulsive disfigurement, repressed anxieties about racial miscegenation, a buried past, ruinous architecture, or any of the other staples of Gothic horror?

That’s just the noun and adjective, “grotesque,” which carries a lot of water around here. Grotesque is basically a single word for my neologism grotto pezzotto - I like to mix things up from time to time. So I gave it a Neapolitan twist. But grotesque will do.

I use it variously to describe: the creative processes of art and history; a mixture of high and low culture, and past and present; Renaissance “rebirth;” revolution; carnival and fertility ritual, bodily humor, interconnectivity, and the earthly cycle of life and death.

That’s a lot of meaning to cram into one little word that simply means “grotto-esque,” or “cavelike.”

The rest requires a story.

In the late fifteenth century, as the Renaissance was hitting its stride in Rome, a young worker was poking around the ruins of Emperor Trajan’s bath complex. I’m told he was a gardener, by my auspiciously-named tour guide, Renata.

“It means ‘Renaissance.’ You can call me rebirth,” she smiled.

That gardener fell straight through the earth - the same earth that the Romans who buried Nero’s Domus and erected Trajan’s column were so eager to placate. He plunged through a cleft in the Esquiline Hill, into what he thought was a cave, or grotto.

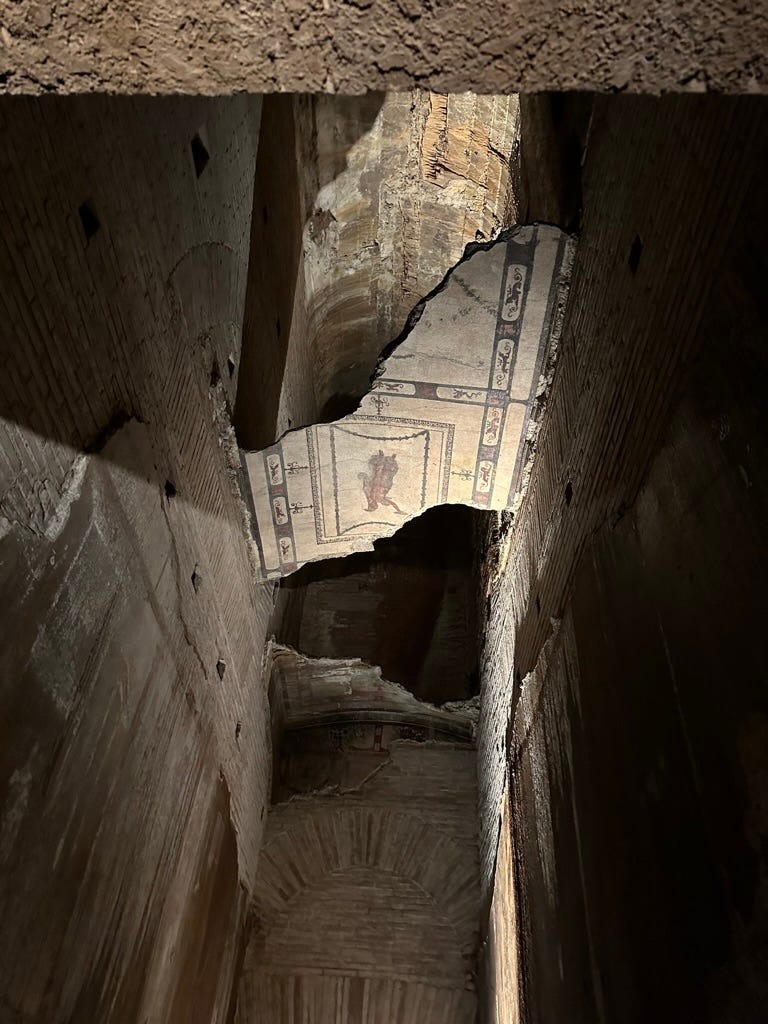

Here’s the hole he fell through (take your pick, others followed later).

The ceiling of the Golden Vault, in the House of Gold. About thirty feet above the palace floor. Today, much of the structure remains underground, where it’s been since Trajan buried it. There’s a park on top, whose roots are intertwined with the structure below, where the city is plotting a garden - which is what covered the ruins of Trajan’s baths in the fifteenth century, along with vineyards.

At the time, the hole above was only a few feet deep. Remember, Trajan filled the whole complex with dirt to ingratiate himself with the Roman public. Like Caracalla, who commissioned colossal sculptures to adorn his own bath complex a century later - the complex where Pope Paul III dug up half of his Farnese collection in the 1540s, several decades after Nero’s palace was rediscovered.

These excavations were an integral part of the Renaissance. The sculpture that marks the inception of the Vatican Museum, Laocoön and Sons, was discovered in the vicinity of Nero’s palace. It’s possible Nero, ever the Graecophile, brought it to Rome from Greece.

Building baths on top of Nero’s Domus had the added benefit of burying what remained of the condemned emperor (with the exception of his Colossus). The commoners tended to like Nero, despite the wild rumors about his vicious immorality and hedonistic excess. He was an artist and performer after all, and these were professions relegated to the lower classes, who loved to watch their emperor kneel before them after a performance, the customary gesture of submitting oneself for applause.

After his death, memories of Nero were so persistent among the public that he was rumored to still be alive, like Elvis, a hundred years after his death. St Augustine was still writing about the legend of “Nero Reborn” in the fifth century. Three people even tried to impersonate the emperor, hoping to assume the throne. This alone was reason enough to suppress his memory. His most fervent supporters, and the insurrectionists who impersonated him, came from the Hellenic East.

While many emperors were declared gods, Nero was turned into the devil. In the absence of a state funeral (he committed suicide before he was deposed), rumors about him still being alive circulated. Meanwhile, the emperor appeared in Hebrew texts, where he converted to Judaism. He resurfaced in Christian scripture (via the books of the Sibylline Oracles) as the antichrist. The Christians he persecuted had ample reason to paint him as the Messiah of evil. A memory damned, but persistent.

By burying the Domus Aurea, instead of erasing Nero’s memory, Trajan accidentally preserved his palace decor for nearly 1500 years, saving it from earthquakes and oxidation. He also gave that gardener a cushy landing, when he fell into it.

So he must’ve had a pretty close view of those frescoes on the ceiling, a few feet above him. What he saw were strange, mythical, hybrid creatures in the distorted light and shadows of the “grotto,” which was really the emperor’s House of Gold.

At the time the ceiling was painted, this decor was nothing new. Images like these adorned every aspiring aristocrat’s walls from Rome to Pompeii, many of them trying to emulate imperial fashions set by Nero.

No one called them “grotesques” in antiquity, because they were never observed in a “grotto,” until a gardener mistook the Domus Aurea for a cave. This decorative style, known as the Fourth Style of Roman fresco, is credited to the artist who painted the Domus Aurea. In grotesque fashion, the fourth and final style is an eclectic mix of the preceding three.

The Second Style was closer to Renaissance painting; it toyed with the art of perspective. Though Roman painters, who were lower class and socially on par with artisans, never mastered the rules of scientific perspective, they came as close as anyone in antiquity. The Second Style was full of masks and Greek images of Bacchus/Dionysos linking it to the world of cult worship and theater, and it derived its illusionistic perspective from the knowledge of set design. It flourished in the late years of the Republic.

Many of Nero’s frescoes appear to be heavily-influenced by the Third Style, which accompanied a lifestyle revolution in Roman society.

With Empire and the ascension of Caesar Augustus, the Third Style emerged, “characterized by fake architectures with spindly unnatural structures that had lost every illusionistic function to become purely decorative.”1 Like the arabesque patterns that emerged from Bagdad in the 11th century, when Islamic iconoclasm prohibited the use of realist imagery, much of the Third Style was “unnatural” and “purely decorative” - at least along the borders.

It often framed an imitation of a painting, which unlike arabesque art after Mohammed, did depict “real” images (realistic depictions of myth).

The Third Style was characterized by a more sober look inspired by the past, reflecting the classicizing taste of Augustan art, promoted by the center of power to reinforce the political message of the founder of the empire, with its focus on tradition and a return to order. This rational, restrained tendency was accompanied by the increasingly unbridled fantasy of the decorative details on the frescoes […] : completely unnatural, spindly architectures, slender plant tendrils and garlands and delicate little mythical creatures willfully paired with candelabra motifs.

MAAN, The Guide, “The early imperial age: decorative motifs and mythical themes.”

The Third Style of the Augustan age was, like Rome before and after this period, conflicted. At war with itself. A tension between imagery meant to reinforce order and stability, surrounded by flights of total fantasy. Part of what makes these images so engaging: they appeal to the imagination, drawing the eye closer. Viewers may think they’re looking at an architectural column or the illusion of a picture frame, only to discover it’s made out of mythical plants and animals.

The scenes at the center of each fresco were often

bucolic scenes […] evoking the sacredness of nature through small cult emblems scattered through the ancient landscape. They have been defined as sacro-idyllic pictures by scholars, who have linked them with the contemporary pastoral poems of Virgil.

—ibid

When the Domus Aurea was rediscovered, the last time anyone had observed such decorative motifs in Rome might’ve been in the previous millennium. Pompeii wouldn’t be excavated for over two centuries, and as far as ancient paintings were concerned, the Renaissance was just beginning to rediscover the classical past. Compared to classical Renaissance ideals about balance and unity, these imperial “grotesques” were paintings of a different sort.

When artists like Michelangelo and Raphael descended into the Golden Vault to observe Nero’s ceiling, the images must’ve appeared fairly strange. Especially in the torchlight, to artists who spent years mastering scientific perspective and measuring the anatomical proportions of the human body. Here were these whimsical, childish distortions of reality and function, little monsters dancing in the shadows.

When we factor in the history of the discovery process, we begin to get an idea of the expansive modern category known as “the grotesque.” Everything from grandma’s wallpaper to Gothic horror and racially-charged musical theater, from bright frescoes to Frankenstein’s monsters and shadowy distortions.

That still fails to cover all the meanings of the word grotesque.

Around the time the Domus Aurea was rediscovered, a writer was born in France, named François Rabelais. Rabelais has been called “the French Shakespeare,” but he’s not known for plays. He wrote ribald, bawdy tales about Medieval carnival. Outrageous tales, considered obscene, especially by the French Catholic Church. The most famous was about a duo of father-son giants known as Gargantua and Pantagruel, which was prohibited by the church. Mostly because it depicted drunken carnival debauchery, and the bodily functions of grotesque giants who did things like put out fires and drown their adversaries in urine. Weird, wild stuff, straight out of the Medieval imagination, written by a Frenchman on the cusp of the Northern Renaissance.

Four hundred years later, in the first half of the twentieth century, a Russian started reading and writing about Rabelais’ tales, and comparing the oppressive religious atmosphere of sixteenth-century France (which was gearing up for forty years of Catholic-Protestant warfare), to the repression of Soviet Stalinism in Russia. That Russian’s name was Mikhail Bakhtin, a philosopher turned literary critic, turned social theorist.

When Bakhtin read the strange “novels,” or collected episodes of Rabelais’ giants, he saw social commentary. He began formulating what’s known as “carnival theory,” a sociological take on some of the strange practices represented in Rabelais’ stories, which he called Rabelais and His World.

Rabelais’ books were wild and outrageous, but then again so were certain carnival rituals - I already mentioned the pagan mystery cults and orgies that were rumored to take place in the grottos of Naples during Medieval carnival, in an earlier post. Carnival was a time of lawlessness and suspended rules, when the populace let loose before abstemious church holidays like Lent.

In addition to drinking, animal-slaughtering and feasting, and (according to the City of Naples) convening grotesque orgies, carnival was characterized by what Bakhtin called “inversion” rituals - a form of tolerated blasphemy. An ass might be led to the church pulpit, according to popular legend, to bray instead of pray. A Boy Bishop was elected to replace church elders, a Fool was elected King For a Day, a Lord of Misrule. These inversion rituals are all reminiscent of Roman Saturnalia, an ancient mid-winter holiday when Romans prayed for the return of spring fertility, and patricians traded places with their slaves, inverting the social hierarchy.

It sounds bizarre at first blush, but the continuities between Roman Saturnalia, ritual sacrifice and fertility worship, mystery cults, and Catholic carnival suggest a form of religious syncretism, in which old forms of repressed spirituality returned during the period of social upset known as carnival.

Bakhtin saw carnival as an example of positive cultural revolution, as opposed to Stalinist revolution, when people were permitted to enjoy a sense of humor and connect with one another across the social hierarchy. By analyzing the writing of Rabelais, who was censored by the Church, he was was making a sly commentary on Stalinist repression in his own time, while hoping to escape censorship himself.

Bakhtin used the word “grotesque” repeatedly to describe Rabelais’ writing, and the social theory of carnival he saw reflected in his text. He called Rabelais’ writing “grotesque realism,” because it depicted the natural cycles of life and death, as well as real bodily functions like eating, drinking and evacuating which, in the vein of toilet humor, elicit grotesque laughter. The grotesque human body in Rabelais and His World consumes plants and animals, passes them out, reproduces, and fertilizes the earth. The archetypal womb, to which we all return. Ashes to ashes, dust to dust.

For all these reasons, it’s hard not to see the story of Nero’s Domus Aurea as the complete embodiment of the word “grotesque” - all the meanings ascribed to it are contained in the history. The building is itself a hybrid network of tree roots and architecture, soil and bricks, once surmounted by fertile gardens and vineyards. The womb of the Renaissance, and the grotesque. The emperor who built it stooped to the creative-class profession of a slave, and knelt before commoners. The emperors after him interred his palace, attempting to bury his past. Fifteen centuries later a commoner, a gardener, fell into the earth and was, ironically, elevated to the perspective of a dead emperor. A past reborn, from underground, during the Renaissance, that proceeded to inform everything from visual art in Europe to Russian theories about carnival - the latter of which sound remarkably like a sublimated form of cult fertility worship. That past is still being reborn, informing our view of Nero and history. Which, as the lady named Rebirth notes correctly, “is not a stable science.” This chamber, colloquially known as the Sphinx room, was just discovered in 2018-19.

By the time I arrived in 2023, it was excavated into a vast corridor.

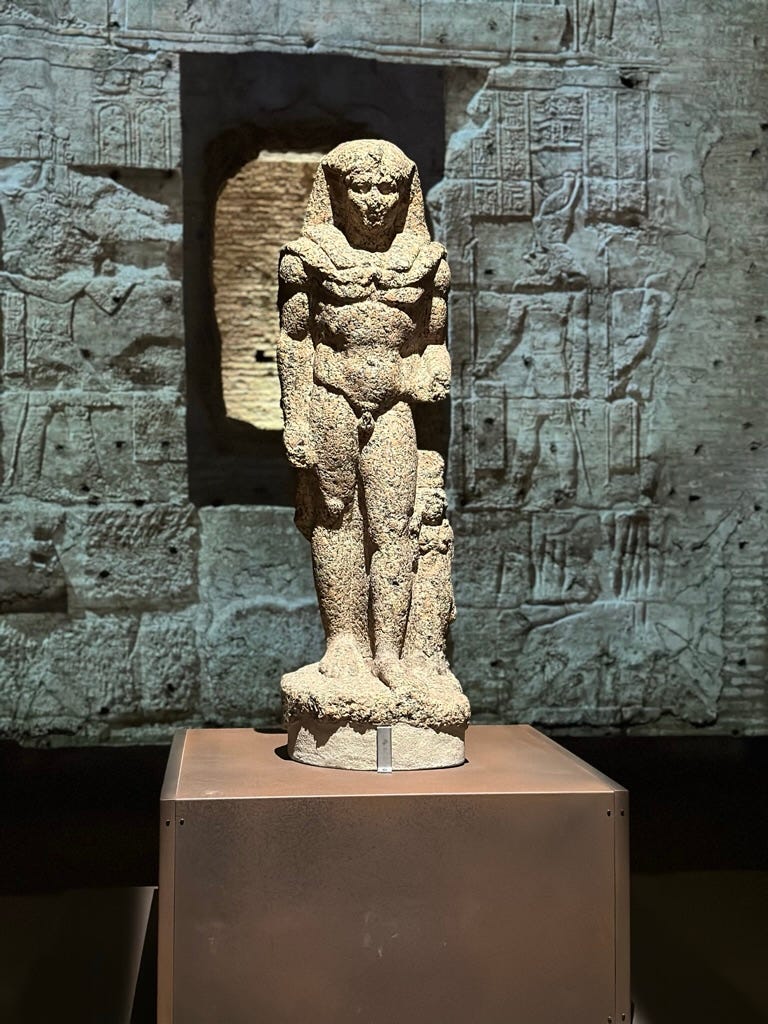

One of the newer exhibitions, now in the banquet hall of the Domus Aurea - a dome structure Nero designed for acoustics and theater performance, and perhaps to house his private art museum, displays artifacts connecting Nero to Egypt.

There are statues of Autokrator Neron (“Nero the Autocrat”), posing as the Pharaoh of Egypt (which technically speaking, he was). A pezzotto combination of Greek and Egyptian sculpture, depicting Roman Nero as the Hercules of the Nile.

Egyptian hieroglyphics on display describe him as the “beloved of Isis” and “Son of Ra,” the Sun. Another statue depicts Serapis, a Greco-Egyptian deity of the Sun, suggesting this is how Nero presented himself—as Apollo. The same way Vespasian presented him, apparently, when he turned the Colossus of Nero into the Colossus of Sol - “now we start to see things coming together,” the lady named Renaissance says.

Like Nero, history is a distorted, hybrid monster. Most of the histories we have of the emperor come from his detractors, upper-class contemporaries from the following generation, like Suetonius, who called him a “poison person.” Pliny called him “the enemy of mankind.” Plutarch’s Moralia suggested Nero’s soul ought to be transferred to a more offensive species. Tacitus, while not fond of Nero, admits that many of these accounts were biased or “falsified through terror.”

History is written by the victors, and Nero lost a civil war with the Roman aristocracy from which he came. His death was followed by years of instability and revolution. There are few histories of Nero written by commoners (except for laudatory graffiti in Pompeii), only the ruling class which despised him. Only Seneca, his tutor and political advisor, wrote positively of Nero (before Nero ordered his death on conspiracy charges).

There’s enough to despise about Nero without sensational propaganda. He tried to have his mother Agrippina killed twice, and succeeded - though his mother ordered killings herself, and was engaged in a power struggle with her son when she died. Her Memoirs are the ultimate source of the dark histories attributed to Nero. His second wife probably ordered his first wife (his step-sister) killed, and Nero may have contributed to his second wife’s death by miscarriage. He ordered the suicides of Seneca, the poet Lucan, and Nero’s hedonistic role model and author of the Satyricon, Petronius. He was a performer to the point of vanity, and clearly overestimated his skill as a chariot racer, poet, musician and actor. His second to last words were “What an artist dies in me!”

“Tutored in democracy,” by Seneca, “he became an autocrat,” Renata the tour guide explains. Educated in literature and ethics, a student of Alexandria and the Orient who retained much of that education, as he began acting like a tyrant.

He probably didn’t start the great fire of Rome to clear space for the Domus Aurea, as critics accuse him in the early histories. The account of him playing fiddle and singing songs of Troy while the city burned is almost certainly fabricated. But he was obsessed with Troy and Hellenistic culture.

He also took full advantage of the fire to rebuild Rome. As well as his Golden Palace - which was really the final straw in public opinion. Ironically, in the wake of the fire he assisted the poor and made Rome more resistant to flame by widening its streets and building spaces, ensuring a steady water supply, and using a fire-resistant brick known as terracotta (“burnt earth”) when he rebuilt the ashes. We’re also told that blamed for the fire, he blamed the Christians, and scapegoated them mercilessly, just as he would be scapegoated by historians and Christian scripture. He went too far even for Romans, using Christians as human torches, according to Tacitus.

Whatever the true history, it’s more complex and obscure than the canonical version, and continues to change as new discoveries are unearthed. The contributions to the history of art contained in the Domus Aurea are vast: the grotesque, and all that the word entails; the impact Nero’s frescoes had on modern art, centuries before frescoes were discovered around Vesuvius; statues like Laocoön that may have been preserved by Trajan’s dirt. All the romance and irony of the Renaissance - moving forward by looking back, discovering the future through the past, the birth of humanism contemporaneous with the discovery of the Domus Aurea - is embodied in this structure.

Whatever his character - and the Julio-Claudians spawned some of the most depraved rulers in the thousand-year history of Western Rome, if we believe the primary sources… Nero wanted to be a human being. He wanted, frivolously and egotistically, to be an artist, if his compulsively-uttered final refrain is any indication (“What an artist…”). He wanted too much besides, and ultimately seeded his own downfall, when he constructed a 200-acre House of Gold on the ashes of Rome. Which lends Nero’s words upon its completion an air of final irony. Still, they reflect a desire to be neither god, nor devil, but human. When the Domus was nearly finished, he was said to have felt

Nothing more than at last I learned to live like a human being.

If the grotesque is said to inspire sympathy as well as disgust, the memory buried in the House of Gold may too.

MAAN, The Guide, “Painting in the 1st century BCE.”