This is surely one of the most inspiring, and often neglected histories ever told, or untold. The story of Andalusia and Islam.

The Scheherazade of this story — like the framing narrator of A Thousand and One Nights, who every evening spins a new yarn into her nesting doll of stories-within-stories, leaving her audience of one, a tyrant who’s resolved to murder Scheherazade once she finishes, spellbound in suspense — is Maria Rosa Menocal, former Professor of the Humanities, Spanish and Portuguese, at Yale.

Menocal has the lyrical gift of rendering history into something like poetry, or music — “a love song addressed to the Jewish, Muslim, and Christian (mostly troubadour) poets” of medieval Spain, as Harold Bloom ("probably the most famous literary critic in the English-speaking world"1) describes Menocal’s artistry in the foreword to her chronicle of Andalusia, or Arabic Spain, The Ornament of the World.

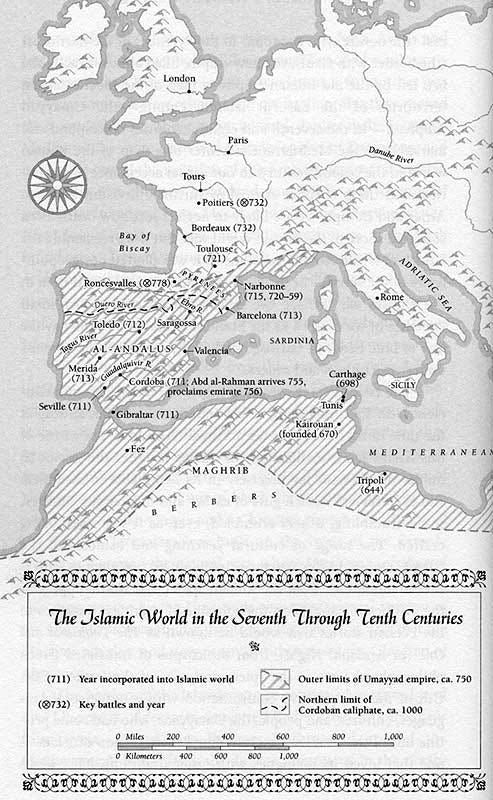

It is the story of al-Andalus, Spain under the aegis of Islam, beginning in 750 — the year an exiled teenager, heir to the Umayyad caliphate in Damascus, after his entire family was murdered in a coup, fled from Syria to the Iberian peninsula to found an empire, and eventually a new caliphate, in Europe. The exile, Adb al-Rahman, seeded a brilliant culture of tolerance, art and learning shared between the dhimmi, or “People of the Book,” the three monotheistic Children of Abraham: Jews, Christians, and Muslims.

Menocal’s story ends in 1492, with King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella marching up the steep road towards the Alhambra, the last citadel of Islam in Spain, in Granada.

Two Catholic monarchs, dressed in fashionable Arab garb, en route to declare this last miniature relic of Islam in the West — a culture and language that once covered most of Portugal and Spain, and inspired all of Europe — devoutly Catholic.

By the time of Don Quixote (1605), Arabic was dangerous to read and write, let alone sing out loud. Part II of the first modern novel begins with Cervantes ‘discovering’ an Arab historian’s account of Lord Quixote of La Mancha, in the Jewish quarter of Toledo. The narrator, along with his Arabic translator, must translate the ‘true history’ of Don Quixote from Arabic into Castilian in secret.

In the years after Ferdinand and Isabella marched into Granada, books written in the lingua franca of intellectual Iberia were destroyed, along with Arabic libraries in Toledo and Cordova, that were once the envy of the Latin-speaking world.

1492 thus marks the tail end of a multicultural renaissance in Cordova and Andalusia, the “ornament of the world.”

Or perhaps The Ornament of the World ends exactly five hundred years later, in August 1992, when, as recounted in Menocal’s epilogue, Serbian Orthodox Christians shelled the National Library in majority-Muslim Sarajevo, nearly destroying a rare Hebrew text carried from Iberia to Sarajevo by those exiles of 1492, the great diaspora of Jews and Muslims expelled from Spain the year that Columbus sailed the ocean blue.

Or perhaps it ends with Menocal’s postscript, written as she was finishing her Ornament to cultural tolerance, the year Islamic fundamentalists attacked New York City on September 11, 2001 — much as their fanatical predecessors had leveled Muslim Cordova a thousand years earlier: the Islamic golden age of Spain was first assailed not by Catholic monarchs in 1492, but by increasingly zealous waves of Muslim fundamentalists beginning in 1009.

Perhaps The Ornament of the World ends long after its Scheherazade was afforded any future tellings. Menocal died in 2012, but her epilogue invokes Salman Rushdie, whose first work published after The Satanic Verses, and the fatwa death warrant the book incurred from the Ayatollah in 1989, was an ode to the Andalusian culture Menocal describes.

Rushdie’s follow-up to the book that nearly cost him his life was mistakenly regarded, like A Thousand and One Nights, as a collection of children’s tales. But Haroun and the Sea of Stories — named for Harun al-Rashid, the enlightened caliph of Bagdad who ushered Greek science and philosophy through the Dark Ages, and disseminated it through Spain — was informed by Rushdie’s love of al-Andalus: “the icon for him, a victim of fundamentalism, of a lost version of that religion and a Golden Age of Islamic civilization,” as Menocal says.

Menocal died a decade before the Ayatollah’s fatwa caught up to Rushdie in 2022, onstage in upstate New York. Perhaps The Ornament of the World ends there.

Perhaps it never ends, or continues its long drawn-out death. As Bloom wrote in Menocal’s foreword twenty-two years ago, “There are no Muslim Andalusians visible anywhere in the world today. The Iran of the Ayatollahs and the Afghanistan of the Taliban may mark an extreme, but even Egypt now is not much of a culture of tolerance. The Israelis and the Palestinians, even if they could achieve a workable peace, would still be surrounded by a Muslim world very remote from the Andalusia” founded by the descendants of that man who fled Syria for Spain in 750, Adb al-Rahman.

That world — which I’ll do well to mediate while The Third Ear is in Spain, as I visit some of the “memory palaces” described in Menocal’s book — contains a sea of stories.

It contains the story of the secular love song, brought to southern Europe and Provence from Bagdad by the qiyan, or singing concubines. It envelopes the story of the troubadours, who changed our conception of love a millennium before the Beatles. Embedded inside that is the story of a linguistic revolution, from Latin to vernacular, via Arabic, and from Muhammed to Dante, Chaucer and Shakespeare. The poetry of the Prophet’s native tongue, long forgotten in the West, transmitted into Hebrew and Castilian, in a language that could sing to god and girlfriend in the same breath, from the temple or the streets. It is a story that begets Western song and literature as we know it, and all the instruments of the modern orchestra. A story that is “first rate,” as Menocal tells it, borrowing the term F. Scott Fitzgerald used to describe something that can contain two or more contradictory ideas at once. Reason and faith, for example. Islam, Christianity, and Judaism. Enlightened religion, and the scourge of fundamentalism. Songs of the sacred, and the profane. An empire of libraries and translation centers, palaces to memory, and garden paradises, humming with the music of libertine slaves that made its way to the courts of England and France.

I’ll tell you a story, as best I can remember it from many years ago — one of a thousand and one.

It captures some of the feeling of reading Menocal’s book, the flash of recognition. The sensation of re-knowing something you suspect you’ve seen, or met before, perhaps in a memory, perhaps in a dream. Like a Syrian palm in California, or an orange grove in Seville.

There once lived a once-wealthy man in Damascus, a man who had a dream.

One night, after losing the last of his wealth in Damascus, he dreamt that he would rediscover it in Cairo — in a far away city, inside a lush courtyard, between two stout palms, buried under arabesque tiles, painted with blue-and-white fawns, adorning a sparkling silver fountain.

So he left his home and he walked, from the middle of the Barada to the mouth of the Nile.

When he came to Cairo he had nothing, and soon found himself in jail. He’d dug beneath every blue-and-white-tiled, fawn-covered, silver-watered fountain that vaguely matched the vision in his dream, and had trespassed in many a respectable man’s courtyard to do so.

When he came before the debtors magistrate, the judge took pity on the Damascene, and asked to hear his story. The once-wealthy man of Damascus told him of his troubles, of the dream of the green courtyard, the two fat palms, and the blue-and-white fawn-faced silver fountain.

“Ha!” said the judge. “That sounds like my fountain — and I assure you there’s no wealth hidden there. You can’t go around digging up fountains in Cairo based on a dream you had in Damascus, expecting to discover treasure!”

“No,” the old man sighed. “I suppose I cannot.”

“Why, I myself had the very same dream last night,” conceded the judge. “But you don’t see me running off to destroy men’s courtyards, or dig beneath fountains. You can’t chase a dream, or trust what isn’t real.”

“No, your excellency,” the Damascene admitted, before the judge interrupted.

“Except in my dream the riches were buried far from Cairo, in front of a poor man’s hovel, opposite the Great Mosque, next to a red earthen wall, under two naked palms, in the dead sand, beneath the cool shadow of their crossing trunks.”

The old man startled.

“You don’t see me caravanning off to Damascus, chasing after halfwitted dreams, do you?,” the judge needled. “Now, leave great Cairo and its fountains, you fool, and never come back! Go before I change my mind.”

The dreamer scurried out of the courtroom, and hurried back to Damascus. He stopped not to eat, drink, or rest. He ran until his throat burned and his ankles creaked, until the sun had withered him to a blistering husk, and he had no sweat left to give. He walked and he walked, until he came to his poor hovel, opposite the Great Mosque, next to the red earthen wall, beneath his two frond-bare palms. He dug in the dead sand, beneath the cool shadow of their crossing.

And he discovered a wise judge’s dream, shimmering in the hands of a fool.

That story about recollecting something valuable and real buried right under your nose, or something like it, comes from my memory of A Thousand and One - aka Arabian - Nights. But it reminds me of the historical poetry of Menocal — as when she descries Andalusia in the Spanish tiles and stucco, and the palm trees — which were transplanted from Syria to Spain by a homesick young refugee from Damascus in the middle of the eighth century, who then wrote a poem about himself as a transplanted palm — of Southern California.

Another flash of recognition, this time about Judaism and Islam, and Christopher Columbus, on Indigenous Peoples’ Day 2024:

The Ornament of the World ends (or does it?) where a previous book by Menocal begins — a scholarly study, as opposed to the layman’s history crafted in Ornament of the World, called Shards of Love: Exile and Origins of the Lyric (1994).

The dust jacket is lifted from an album cover, Layla and Other Assorted Love Songs, by Derek and the Dominoes (inspired by the tragic love story of Layla, from a 7th century Arabic poet).

In the first chapter of Shards of Love — “Horse Latitudes,” featuring an epigram from the Jim Morrison poem, or Doors song of the same name, about jettisoning horses in the transatlantic doldrums in the hopes of catching wind — Menocal sets the scene of Cristóbal Colón’s departure from Andalusia to the New World.

It is August 2, 1492. Or in the Hebrew liturgical calendar, the 9th of Ab — the anniversary of the destruction of the Second Temple, the beginning of the Jewish diaspora in 70 AD.

An influential rabbi had pleaded with Ferdinand and Isabella to postpone the expulsion, for a few weeks, of what were derisively known as the Moors, or Muslims, and the Jews, from Catholic Spain.

The rabbi engineered the date so that the exile of the Sefarad, or Spanish Jews, would symbolically coincide with their ancestors’ diaspora from Jerusalem. Columbus was forced to set sail from an inferior port, in Palos, because the larger port city of Cadiz, just to south, was too overwhelmed with wailing, and too overcrowded with Jew-and-Muslim-bearing ships leaving Spain, to accommodate Columbus’ voyage of discovery.

Many of those early exports — “colonizers,” in the parlance of today’s moralism — from Spain to the New World were exiles, whether Muslim, Jewish, or Christian conversos (the forcefully converted), from Andalusia.

The date that marks the last gasp of a multicultural golden age in Andalusia for Menocal — ironically, the beginning of the so-called Siglo de Oro, or “Golden Age” of imperial Spain — the date that is commonly used to mark the beginning of the Early Modern era, Aug. 2, 1492, saw the expulsion of two-thirds of Spain’s multicultural heritage.

Some of that multiculturalism was aboard Columbus’ ship — the learned translator who accompanied Columbus, expecting to encounter the lingua franca of India and the East, spoke the language of the Prophet. The first time a Spanish translator spoke to a Taino chieftain on the island of Cuba, he addressed his Indigenous interlocutor in Arabic.

“What is conspicuous in the standard narrations” of this beginning of the history of colonialism, Menocal writes, “even those of 1992 that indulged in all manner of supposed soul-searching, is that the two [events] are divorced to such an extent that it is only the suggestion that Columbus might have been one of the Jews himself that calls our attention to what we then call the ‘coincidence’ : the voyages of exile and the voyage of discovery begin at the same hour, in the same place.”

Christopher Columbus, Menocal theorized in 1994, was likely a Jewish exile or converso, a Sephardim from Catholic Spain.

In October 2024, just in time for Columbus, or Indigenous Peoples’ Day, a new documentary, “Columbus’ DNA, his true origin,” came to the same conclusion.

The colonizer par excellence, Columbus, was thus affected by the same backwards policy that expelled Muslims and Jews from Spain, under his patrons, Ferdinand and Isabella. It may have determined his decision, as it did those of other Spanish Muslims and Jews, to sail to another world.

Of course, as Bloom said in his foreword to The Ornament in the World in 2002, rather bluntly: “Our current multiculturalism, the blight of our universities and media, is a parody of the culture of Cordoba and Granada in their lost prime.” To announce that Columbus was a Sephardic Jew in October 2024, days after the one-year anniversary of Oct. 7th, and days before the anniversary of his birthday, was not to varnish his reputation but to tarnish it further, as that of not only a colonizer, but a Zionist before the fact. Instead of complicating and co-implicating the history of East and West, of Jews, Christians, Muslims, as Menocal has, our current brand of multiculturalism reduced Columbus to an avatar for the war in Gaza.

The culture of Andalusia, in which Muslims and Christians fought alongside each other against despotic fundamentalists of either faith, where the vizier to the caliph was the peninsula’s most educated Jew, and the dhimmi intermarried and interconverted, translated, philosophized, and sang to each other, for Bloom and Menocal, was true multiculturalism based on a shared aesthetic and intellectual vision, not politics or religion.

The period that began in 1492, the Modern era of Catholic Inquisition, imperialism and conspicuous conformity, was, in Menocal’s words, an era of Spanish “political correctness,” of religious and nationalist “identity.” For Bloom it marks the beginning of the long, devout death of Old Spain, chronicled in Don Quixote, that finally ends with the last gasp of Francisco Franco in 1975.

Over the next several weeks I’ll translate a few drops from the sea of stories collected in the books of Menocal and others, a few pearls of wisdom from the ornament of the world — the rich history of Andalusia, the golden poetry of Islam, the love song, and profane literature written in the language of the streets and sung by court troubadours, as I dig for it in the memory palaces of Spain.

Selah.

Oxford Bibliographies