Early in the Information Age, a celebrated media guru now considered ahead of his time, Marshall McLuhan, claimed that “the artist alone” was responsible for recognizing patterns in the cultural carpet, rendering the onslaught of modern media semi-intelligible.

Now we have AI.

I suspect we’re at the point where most of us are performing a desperate, often misleading version of pattern recognition. As a survival mechanism, in the age of information overload.

Looking for coherent meaning in the shattered mirror that is post-internet life.

Or maybe I’m just strange and misguided.

Whenever I confide one of the many serendipitous overlaps or mystical coincidences—the patterns I’ve encountered on my journey to Italy thus far—my observations are typically met with silence or perplexity.

Like I’m speaking in tongues.

Even my guide in Naples, who like many native Italians, especially in the South, is a fairly mystical and historically-minded human being, seems to think I’m reaching for something. (Which of course is true.)

No one says as much. They utter some silent version of what the guide usually says: “Eh… Okay.”

“Ah!”—if the point gets across successfully.

Some things simply get lost in translation. Others require supplementary explanation…

Andrea, la guida, told me with a straight face that the sweet-smelling myrtle leaf, evergreen and ubiquitous among the local ruins, is known as the “Bush of Venus.”

Andrea speaks my language, in more ways than one. He’s aware of the English double-entendre, and knows his way around a dirty joke. But I stooped so low as to explain his unintended pun.

I try to recognize cultural patterns, with an epicurean sense of humor at The Third Ear. Unavoidably, the process of mental association is filtered through the space between my ears, after I hear or learn something from others. The patterns are personal, in the end, but also a way of processing cultural history, related to me by the guides and teachers I meet along the way.

In Italy, in Oklahoma. In books, cemeteries, or art, or anywhere else.

The first ear is the source, whatever that may be. Readers are the second. Consider this the third.

Your translator between worlds. Capisci?

Capiche? You will. As the guide says, “I’ll take you.”

Through the story, one step at a time.

I’m staying in an historic hotel, in Naples, to cheer myself up in the wake of bad news from home. More importantly, to entice my son to education through a combination of indulgence and instruction. After I drag him through the Vulcan dust each day— tunnels and ruins, Christian chiesa or pagan templi—we bathe and swim.

Naples is refreshingly affordable (once you get here), but I splurged for la camera—the box. Our room.

The lens looks out on an ancient island. Once a Roman villa, where the last emperor was exiled after the fall of Rome. Later it was fortified into a defensive outpost, then demolished by the Neapolitans who constructed it—during the Muslim conquests of the Southern Mediterranean. So it couldn’t be captured and turned against the locals by Saracen raiders from North Africa. Today it’s adorned with a medieval castle, surrounded by a small fishing village, named Castel dell’Ovo.

“The Egg Castle.”

The name derives from Rome’s poet laureate, Virgil. Later considered a pre-Christian prophet by medieval Catholics. A man who placed a legendary egg inside of a jar. Inside of a box, inside of a cage… read last week’s installment for the rest of that story. The beginning of The Mysteries.

The small-craft marina in front of The Egg makes for a shallow saline pool, as it did the afternoon we arrived. Through a hole in the wall, we passed and dove into the open baia—the Bay of Naples.

After our first sunset, and every evening after, the ramparts of “The Egg” became a symbolic omen. In my mind, at least.

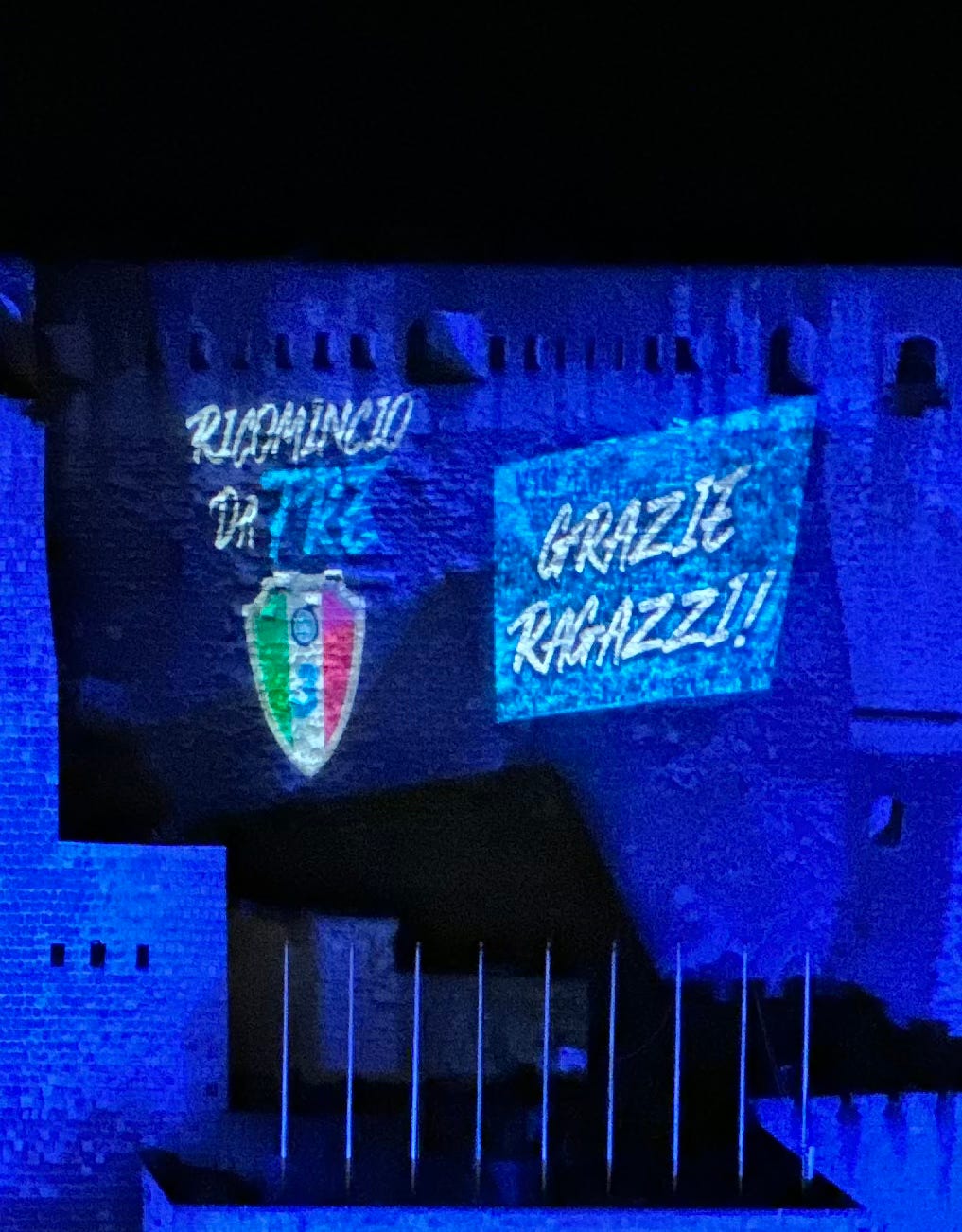

I may be projecting—but some locals are projecting my name and number onto the wall of their Egg each night. Again—this is psychological, almost ego-maniacal. Still, this is what I see every nightfall.

Not to suggest anyone should take internet translators seriously, without a heavy dose of irony, but as far as I can ascertain from the web and what little Italian I know, the message above transliterates to:

“Begin Again from Three. Thanks Guys [Boys]!”

There was a welcoming gift in our room, waiting on the correspondence desk the day we arrived. Waiting for the little guy to ask, “What’s in the box?” the following morning.

“Open it…” I winked. Thinking to offer him a treat.

He tossed me a lucky charm instead. “Think fast!” Gifted me a trio of fertility horns.

In exchange for the gift, I dragged my kid through the Park of Virgil after breakfast, in the heat of the morning. Overlooking peninsular Miseno, where Pliny the Elder sailed from his villa to investigate the eruption of Mt. Vesuvius.

The commander of the Roman fleet, strategically situated in Naples, Pliny was also a naturalist and historian. He died of curiosity, during a quest for scientific investigation, sailing too close to the volcano. His nephew stayed behind at the villa, surviving to become Pliny the Younger, and report his uncle’s findings to Tacitus, another soldier of curiosity.

While we traced Pliny’s voyage, I asked The Third Man, our guide Andrea, what all the “3”s were about.

I didn’t mention the lucky charms yet. La guida carries a red one, the traditional color of a local chili pepper and aphrodisiac. Long before that, the charm was associated with animal prosperity, horns and Priapism. Andrea says he found his the ground.

To which it belongs, from whence it came. Until Andrea picked it up and put it in his pocket. The cornicello (the horny jewelry shown above) is rooted in fertility worship. Death and chili peppers, the spicy seeds of rebirth. The vegetable symbol of Priapus.

Priapus is the god of something to be whipped out later. Too soon to unveil that mystery.

I don’t see why I need three of his emblems, but I’ll take all the help I can get.

Anyway, I knew none of this at the time. I wasn’t curious about the three horns, I was curious about the “3” on the wall outside my window, and everywhere else.

Napoli just won their third Series A championship, Andrea explained. For the first time in 33 years. That’s what all the “3’s” were about, for Napoli football fans—a triumph for their team. The Partenopei, or “Sirens,” synonymous with Naples itself. “The Mermaids,” as Andrea translated this euphemism for Neapolitans, to the benefit of my son. They’ve been celebrating since May, but la guida said “June.”

So I interjected.

I’d already explained the concept behind The Third Ear to Andrea—he’s a storyteller himself, a sympathetic ear… and mouth.

I began to mention that I was born last month, projecting some kind of third-hand significance onto “June” and “3”—before he interrupted me.

“Ah, a Twin!”

He was referring to the Zodiac sign, which I recently learned I share with Bob Dylan. June bugs.

I let Andrea skim my Woody Guthrie coverage, on the ride to Virgil’s park. The folk songs about Mermaid Avenue in New York and volcanoes in Southern Italy, the song he wrote for Ingrid Bergman and Stromboli, and my own sighting of the actress in the lobby of the Vesuvio hotel.

Where she refused to speak to me, while we waited for the elevator.

Andrea’s never heard the name Woody Guthrie, or his song about “Ingrid Bergman” and volcanoes, or “Mermaid Avenue,” but neither have most Americans. He did recognize the melody to “This Land is Your Land,” however.

Just as many Americans intuitively recognize certain Italian melodies, but not the names of their source.

Most of the best singers in Italy hail from the South, Andrea boasted, which even a cabbie in Rome had to admit. (Italy is rife with regional rivalry—food, football, legends and tradition, songs and beauty. To each its own: “the best.”)

So too with Sophia Loren, who hails from the South, where she grew up. We were about to pass through her hometown near Pozzuoli, en route to Cuma, north of Naples.

Technically, the self-styled “Viscountess of Pozzuoli,” of humbler origins than her adoptive title suggests, was born in a Roman hospital. But there are certain origin stories one doesn’t mention in either region, Rome or Naples.

Like the name on Loren’s birth certificate, the origins are changed and reinvented to suit various ends. Where the actress was born, where she went to high school, the origins of the Colosseum, the first dome structure in Italy… Et alia, et cetera.

Watch what you say and hear, about origins.

Unless it’s clear you’re joking. I’m biased towards Naples and the South because I came here first for a reason, but it’s wise to hold your tongue.

Like Southern Italian singers and actresses, and American melodies, Andrea was familiar with Bob Dylan. (He especially appreciated Dylan’s laconic response to receiving the Nobel Prize in literature: Dylan’s version of “Eh.”)

I asked if he’d heard of him.

“Yes! I like him very much. But he is dead… or no?”

No. He’s a Gemini.

I began to tell la guida about Bob Dylan “the Gemini” “butterfly,” always changing shape and form, with a mind flitting this way and that, but Andrea was distracted by my son.

“Arri-son, what are you?”

The fruit of my loins has no idea what the Zodiac is, let alone his signature in the cosmos. To be honest, neither did I. Like life, I take astrology half-seriously at best.

Most of the Time.

“Ares” sounded like an appropriate guess, given the way Andrea pronounces my son’s name. Which, as the toaster said to the bread, actually begins with an “H.”

The Miracle of Naples occurred only yesterday, quite by accident, so Andrea had yet to adapt to this Germanic initial.

“Arri-son: When were you born?”

April.

“You’re a Bull,” said the guide to the perplexed, my ten year old. “A Taurus. I think maybe you are a thinker. Slow to anger unless moved?”

Silence, followed by my attempt to translate.

La guida interrupted me again, to deliver a more rhapsodic explanation of astrology and planetary magnetism than my own.

“Let me tell it.”

Okay, Andre.

“You know the planets, the Sun, are like gods. Magnets…”

By the time we approached the car, Arri-son was sun-dazed and mystically confused. Nor more than he would’ve been if I had tried to explain the music of the spheres. He was thirsty for something clear, and cool.

We stopped to buy some water.

Since the vendor lacked change, I told him to keep the tip. He offered me something else instead.

No bullshit.

A can of Red Bull, with red horns. “Eh?”

I offered my son a symbolic sip in the car, but he demurred. Initially.

He’d already tasted espresso that morning, and had yet to realize Andrea had turned him into a bull. He was pensive for a moment…

“What does Red Bull taste like?”

He asked too late, as I drained the last drop of Taurine. Hadn’t tasted ox bile in years.

“It’s not bad.”

I think he would’ve enjoyed it. We’re not so far apart.

On the way to Cuma, Andrea and I entertained ourselves with stories—mostly his. Better to listen, when you’re in another country.

We drove up Via Petrarca, while Andrea reminded me that Naples was where Petrarch fell under the spell of the unattainable.

In his case, the daughter of King Charles of Anjou. The father of Renaissance poetry’s idealized lover, Laura.

Petrarch’s muse. Unrequited love.

Like Boccaccio’s “Little Flame,” Fiammetta. Also out of reach.

Like Dante—who accidentally revolutionized Catholic doctrine in the process of writing poetry—Petrarch and Boccaccio revolutionized Italian literature while idealizing an unattainable female courtier.

Following the lead of Chivalric romance, court troubadours, and Mariology—worshipping the Virgin Mary. Feminism on a pedestal.

The latter two (Boccaccio, Petrarch) spotted the object of their desire, and subject of their poetry, in the same church, on Easter Weekend in Naples.

Locked eyes, perhaps, in the chapel of San Lorenzo, but never lips. In the Chivalric tradition of courting what can never be consummated: desire attained is desire lost.

Italy’s answer to buddhism, via Greek Hellenism. Asiatic and Arabic love songs, finally co-opted and sublimated by stuck-up aristocrats and people outwardly devout.

Ripe for parody in Boccaccio’s earthy prose-poetry.

Each of these places, like the Church of San Lorenzo, contains a story in itself. A book of stories. Which I’ll finish tomorrow.

So keep your pantalones on. They haven’t been invented yet.

San Lorenzo, whose church bears his name, was roasted alive on a grill. Cooked on one side, he goaded his tormentors:

“You can flip me over now, this side’s done.”

Some Eastern stoicism here as well, mixed with a healthy dose of epicurean humor.

We saw one of the many alleged homes of Vulcan, the Italian Maui. God of fire and forge, in the crater Solfaterra.

Here Andrea once brought PBS travel-show host Rick Steves, and fanned a volcano vent to anger with what looked to me like a colossal joint—a rolled cone of newspaper (he provided video evidence, look it up).

Andrea can’t perform that trick anymore. The crater is off limits to pyromaniacs. And everyone else, thanks to one sad story.

A family tragically fell into a shallow hole in the sulphur pits, less than two meters deep. Asphyxiated by carbon monoxide, one after another. Mother to rescue son, father to rescue mother, and an uncle who survives, with severe affliction, from the final attempt.

San Genarro was beheaded in the center of this crater, after several failed attempts to kill him. Petting lions sent by the Romans to devour him.

Another Southern saint, still venerated in his chapel down the road. Worshipped in colorful fashion, unrecognized by the Roman Catholic Church. Involving a magic vial of his blood, which inexplicably liquefies every year on certain dates.

If the blood fails to run, his adherents, a sisterhood who claim to be related to Genarro by blood, switch from praying to cursing in his church. A building inhabited by dogs and guitar melodies as well as humans and organ music. Another mystery cult, another book of embedded stories, for another day.

Andrea claims the sulphuric earth (where San Genarro lost his head), the whole crater, has healing properties.

He knows a man who used to compress small bricks of ash from the caldera, little tufa, to sell to tourists. Andrea calls him Lucifer.

Lucifer, accustomed to breathing smoke, lost his voice to cigarettes and throat surgery.

Before the tragedy, when the crater was still accessible, Lucifer returned to work. Without his voice, which was stolen by the surgeon’s scalpel.

As soon as he inhaled the sulphuric steam post-operation, he regained his ability to speak. Only so long as he was in the volcano, and just enough to be understood.

It’s been scientifically proven that the geothermal vapors of Solfaterra act like gaseous Viagra, Andrea says.

Ironic, no?

“Why?”

Because the Greek version of Vulcan was mythically deformed, some say impotent. Tempting Venus to philander with Mars.

“Ahh… !” said the man who used to mess around with volcanoes. “It’s funny, no?”

These are all distractions, stories and places we passed along the way. Things we remembered, and forgot.

On the oldest road to Cuma. Come, “I take you.”