To quote Dan Stone on parenting: “By many contemporary measures, I’m a bad parent.”

Substack’s Head of Culture and Music was speaking about the time his two-year-old son, confecting mud pies, shouted across a playground: “Hey Papa—This pie is gonna be fucking yummy!”

It made Stone ruminate on the works of Lenny Bruce and George Carlin: on profanity, parenting, and speech.

I’m speaking about the time I took my son to “Portslamdia,” a DOA Wrestling event. Which makes me reflect on the works of Susan Sontag and Clement Greenberg: Camp, Kitsch, and Kulturkampf.

Read about “Profanity and shit,” and hear Stone speak with producer Rick Rubin, at Hey Pop.

“Camp” and “kitsch,” surely, have been used to describe pro wrestling. And numerous “culture-war” signifiers were on display that night in the ring, among the paraphernalia of wrestling props. Or agitprops.

But reading cultural signifiers in my neck of the woods is like reading entrails. As recent standup routines attest—it gets messy.

Portland is, to bowdlerize one comedian, a bunch of woke rednecks. You might be menaced by a biker with Hells Angel tatoos, only to learn he’s vegan, and a buddhist.

In a similar vein, DOA Wrestling—the Disciples of Apocalypse—was originally coded as a band of warring motorcycle gangs. Today its arch “Weirdo Hero,” Ravenous Randy, is coded as a nonbinary version of the Joker.

To unpack this, I’ve been wrestling with the recent history of sportive combat. With A.J. Lieberman’s boxing coverage in The Sweet Science, Rocky Marciano and Hulk Hogan, high and lowbrow art, class struggle, aesthetic theories, and even… totalitarian propaganda.

Tragically ludicrous, yes.

But “Portslamdia” somewhat disturbed my kid, and/or bored him to death. By the third bout, he’d retracted into his hoodie shell, to “take a nap,” he said—soothed by the lullaby of percussive body slams. Confused into disassociation, perhaps, by the onslaught of costumes and culture struggles. I’m still forming my own take on the matter, and the matter of taking him.

(Now that I’m through, I regret it.)

True, my parenting snafu involved profanity, in the sense of “the seven words you can’t say on television,” or in front of your eleven-year-old. But DOA Wrestling also involved profanity in the sense of what’s pro-fanum: “before the temple,” or un-sacred. Though as you’ll notice, wrestling has as much to do with what is sacred as with what’s not.

That’s part of the modus of performative wrestling, one gathers: the heels embody what a crowd deems profane or offensive, the heroes or “faces” restore the collective sense of what’s right, or lose trying. And the heroes do lose, often. A parody of catharsis, maybe.

I expected profanity, of the variety used by Dan Stone’s two-year-old son. Not to mention my own—when he was four, frustrated with a Lego, he intoned (in exact imitation of his father): Th’s fuckin’ thing.

You assume there will be profanity. You don’t assume there will be blood. Not the blood of combat, mind you, but menstrual ichor, seeping through the leotard of the amazon in the opening bout. The first hint that this evening will be about in-your-face gender dynamics, a travesty of political theater.

There will be a looming, late-middle-aged inebriate (perhaps a vegan biker), slurring war stories to his buddies through American Spirit smoke, in the line to get in. To what looks suspiciously like a dive nightclub, and in fact hosted a rave the night before.

A medium-sized venue, as nightclubs go, in the warehouse district. Minuscule, as far as wrestling venues go, to anyone who vaguely remembers the era of Hulk Hogan—a regional affair, intimate and personal; we’re in the first row. It might get loud, the jar of disposable ear plugs at the door suggests.

There are other young people, a few, mostly my son’s age. The sign at the entrance welcomes “All Ages.” The pronouncement is deceptively tone-deaf, in hindsight, like the parental advisory before a Manson documentary that cites partial nudity and smoking.

There will be blood.

There will be bad taste.

Of all the dissertations on the subject, no one has defined Camp more succinctly than John Waters, on The Simpsons.

In a 1997 episode (“Homer’s Phobia”), an animated version of the cult director stood before shelves of mass-produced kitsch—Trolls, Transformers, a Godzilla figurine, piggy banks, inflatable furniture, Last Supper TV trays, and other “valuable worthless crap”—and defined camp as, “the tragically ludicrous, the ludicrously tragic.”

The Simpsons visit Waters’ collectibles shop to hawk what Marge believes is her grandmother’s Civil War heirloom—a Confederate soldier figurine that turns out to be a “Johnny Reb” liquor flask from the 1970s, worth two books of Green Stamps.

Which pretty much sums up kitsch: mass-produced “worthless crap” from grandma’s basement. “Valuable” is where camp enters the equation—and bad taste is part of the appraisal. Waters’ curation of certain kinds of crap, in other words, is what makes kitsch “Camp,” and lends it sophistication.

Tragically ludicrous. Bad taste as taste.

As far as bad taste goes, a Confederate flag, or even (in the annals of punk fashion) a Swastika donned for shock value, is a bridge too far for most curators. But these emblems are actually closer to the original conception of kitsch than say, the Rex Mars Atomic Discombobulator in Waters’ shop.

They’re closer to the symbology of regime.

In 1939, art critic Clement Greenberg published a seminal essay on aesthetics in the age of mass production, “Avant-Garde and Kitsch.” He noted, as others were at the time, that kitsch had become the official aesthetic of the Soviet Union, Socialist Realism.

That, as World War II was beginning to wax truly horrifying, kitsch had become “the official tendency of culture in Germany, Italy, and Russia.” A way of co-opting the art of the masses, to ingratiate the ideology of the regime with the people.

Kitsch was not solely the domain of Soviet communism or Nazi fascism, of course—though the word was appropriated from the German for “trash” or “smear.” On the contrary, Greenberg was trying to account for how the same culture—American culture, and that of other industrial democracies—that produced T.S. Eliot poems could also produce songs by Tin Pan Alley.

High Modernism, and pop.

To Greenberg’s point, it’s worth noting that around the time T.S. Eliot’s The Wasteland was published, another American literary giant, Arthur Miller, was auditioning songs for Tin Pan Alley.

What Greenberg was getting at in 1939 was a collapse of the distinction between high and lowbrow, elite and popular culture, that artists like Andy Warhol and Bob Dylan would carry to fruition in the 1960s. At the beginning of WWII, it seemed “entirely new, and particular to our age,” to the critic. And not entirely positive.

As a society . . . breaks up the accepted notions upon which artists and writers must depend in large part for communication with their audiences . . . It becomes difficult to assume anything. All the verities involved by religion, authority, tradition, style, are thrown into question, and the writer or artist is no longer able to estimate the response of his audience to the symbols and references with which he works . . . the really important issues are left untouched because they involve controversy . . . nothing new is produced.

One response to this cultural confusion was the avant-garde. Modernists like T.S. Eliot and Picasso—whose own prints, mass-replicated as they are, have become a form of kitsch themselves.

Another response, available to all, was immersion in products of mass production. The funny papers, Hollywood movies, or The Saturday Evening Post. Both, Greenberg estimated, were retreats into style over content—"art for art’s sake” and “pure poetry” in the case of Modernists, kitsch for the masses.

Among critiques of the 2020s (as I discussed here), there has been much ado over whether culture is “dead,” “stagnating,” or “stuck”—most argue it is, with the exception of one lonely “Internet anthropologist” arguing it has taken new forms online. Example:

Culture and human behavior certainly take new forms online, though one can argue whether AI constitutes art. One could argue that memes, with all of their ideological baggage, are the new synthetics of mass-reproduction.

Call it neoKitsch. Call it Campf.

Or maybe it already has a name—Slop.

In the 1920s, the central concern of artists, and later critics like Greenberg, was also cultural stagnation, or avoiding it: to “keep culture moving in the midst of ideological confusion and violence.” Artists retreated into pure form and abstraction, reflections on the processes of art, which once strove to imitate the real world. Now it imitated itself—"the imitation of imitating,” in Greenberg’s words. Which also describes Turing’s test for Artificial Intelligence: “the Imitation Game.”

Simultaneously:

With the entrance of the avant-garde, a second new cultural phenomenon appeared in the industrial West: that thing to which the Germans give the wonderful name of Kitsch: popular, commercial art and literature with their chromeotypes, magazine covers, ads, slick and pulp fiction, comics, Tin Pan Alley music, tap dancing, Hollywood movies, etc., etc.

Fine. What does the Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction have to do with Wrestling in the Age of Artificial Intelligence?

Kitsch is mechanical and operates by formulas. Kitsch is vicarious experience and faked sensations. Kitsch changes according to style, but remains always the same. Kitsch is the epitome of all that is spurious in the life of our times.

It borrows from other forms of culture “devices, tricks, stratagems, rules of thumb, themes, converts them into a system, and discards the rest. It draws its life blood, so to speak, from this reservoir . . .”

Which brings us back to menstrual ichor.

I don’t know if the woman in the opening bout intended to expose the audience to her cyclical privations (assuming they weren’t staged), or if “the show,” as they say, “must go on.”

But it reminds me of something Susan Sontag wrote in 1964, about “the sensibility—unmistakably modern, a variant of sophistication but hardly identical with it—that goes by the cult name of ‘Camp’” :

I am strongly drawn to Camp, and almost as strongly offended by it . . . To name a sensibility, to draw its contours and to recount its history, requires a deep sympathy modified by revulsion.

—Notes on “Camp,” 1964

Camp, as Sontag says, “converts the serious into the frivolous.” I’ll give you an example.

Randy Myers, the self-styled “Weirdo Hero” of DOA Wrestling, was estranged from his father at the age of ten. His mother’s best friend, a gay man who became Randy’s surrogate father around the same time, died of AIDS in the early 90s, when Randy was my son’s age, eleven.

Serious trauma.

In YouTube interviews from 2021, Randy Myers comes across as a mostly-straight man in his late thirties. Though his hair is long and green, and he teases it occasionally, while he and the host of “I’m Probably Wrong About Everything” discuss the availability of the words “dude” and “man” to people, like themselves, not wishing to buttress the patriarchy. The host doesn’t wish to offend Randy’s sensibilities, using these as an exclamation—“dude, man!”—as the local hero discusses his weightlifting regimen, and kids dressing up like his character for Halloween, in the register of Mickey Rourke’s baritone from The Wrestler. In a gruff voice, he describes his childhood, and the loss of his mother’s friend and father figure, holding back tears.

Onstage, “in the cage,” “Ravenous” Randy is introduced with a projection of his mug, plastered in the white face paint and black-and-green eyeliner from Heath Ledger’s Joker, mincing effeminately on the screen above his walk-on routine, as he prances out of the greenroom. He has a torso to make Iggy Pop blush.

It’s a double bout, and the Weirdo Hero—the crowd fave—along with his sidekick dressed like Robin, are set to tag-team a pair of ladies, the “Hells Belles.”

One of the Hells Belles is of a type—call it Hot Girl—“Baby One More Time” but with shades of French Maid and Sexy Nurse instead of Schoolgirl, played by a petite Latina. Her partner could pass for a nonbinary man, but reads as Butch Lesbian, hulking under a purple pageboy cut and gothic makeup. The teams size each other up; the bout commences.

The contest hits an early snag, when the Hells Belles fall to infighting. Purple Pageboy refuses to tap-in for Hot Girl. The show’s sole representation of Hot Girl femininity, the flirt in a skirt, has been vamping for the crowd, you see, not taking the bout seriously. She gets a taste of humility, it’s understood, as two gender-fluid men bend the rules, teaming-up on her while Pageboy’s back is turned. Finally, when Pageboy is satisfied Hot Girl has learned her lesson, she turns around and taps in.

Other highlights, wrestling fans, include the Hells Belles getting the better of Ravenous Randy with a belt. To which he responds masochistically: “Choke me… harder!”

A prop inexplicably appears in a corner of the ring. A white door, leaning expectantly, waiting to receive some airborne body in motion. It’s the Newton’s First Law burlesque—an object at rest tends to stay at rest, unless acted upon by another body. In the end, it’s that of the larger woman, who’s hurled through it. Glass ceiling, composite door. Team Ravenous wins.

Recall that every bout has a sacred hero, and every bout a heel (or two). In this round, it’s the Hells Belles.

The most infamous heel in Portland history, or the wider world of PNW wrestling and beyond, was arguably “Rowdy” Roddy Piper, a “Scottish” native of Saskatchewan. Rowdy Roddy, like Ravenous Randy, had an early falling out with his father, and found solace in wrestling.

Before he came to Portland, Piper made a name for himself antagonizing L.A.’s Latino community. He promised to make amends, offering to play the Mexican national anthem on his signature prop, the bagpipes. He played “La Cucaracha” instead, inciting a riot. He then went on to feud with a trio of Mexican-American wrestlers, the Guerreros, in the Los Angeles area and America’s Heavyweights Title, as the “Masked Canadian.” Before joining Don Owens’ Pacific Northwest Wrestling circuit, a precursor to DOA—the home of Gorgeous George. PNW once pitted a wrestler against 1920s heavyweight champion Jack Dempsey, a boxer. (Remember this, when we get to Rocky and Hulk Hogan.)

Rowdy Roddy later went on to fame in the WWF, WWE, and WCW, whose heydays overlap with Piper’s (about 1996—2011). Vince McMahon called him “one of the most entertaining, controversial and bombastic performers ever.”

Piper died in 2015, which I suspect marks a new era in the topos of heel-baiting: gender and sexuality supplanting race and ethnicity. Rowdy Roddy’s ashes are interred in Oregon.

The heel in the pre-match show—facing-off against Eliza True, the menstruating heroine—is Cole Rivera. Cole is a buff, old-school cisgender gay dude with no shirt and natural hair color. At least in the eyes of one man in the crowd, less “woke” than “redneck,” who repeatedly shouts, “You suck dick!” It’s the only taunt from the audience that’s censured that night, over the P.A. system, much later. Long before that, Cole defuses his heckler with “Is that a bad thing?”

The heel triumphs over Eliza True, who is now free to apply something that offers 360 Degrees of Protection, No Matter What Your Sport, her pre-match show concluded.

The match proper begins with the defeat of another heroine, at the hands of another buff heel. The romantic partner of the vanquished steps forward to carry his heroine off the mat, and harangue her heel. The beau is yet another buff man—a good one, finally, wearing a “Protect Trans Kids” T-shirt, the one with a dagger and rose.

By now the crowd has learned to suffer the demise of its principles, as the heels win. The restoration of virtue occurs when a pair of Mexican-American brothers, dressed like Aztec warriors, defeat their white opponents, recalling the days of the Rowdy Roddy Piper, the Masked Canadian vs the Guerreros.

A few more Notes on “Camp,” from Sontag’s list, before we continue, which may or may not describe pro wrestling.

Camp sensibility is disengaged, depoliticized — or at least apolitical.

[Camp is] the love of the exaggerated, the “off,” of things-being-what-they-are-not.

The androgyne is certainly one of the great images of Camp sensibility.

Camp is the glorification of “character.”

The whole point of camp is to dethrone the serious. Camp is playful, anti-serious.

[Ours is a] culturally oversaturated medium . . .

[The connoisseur of Camp finds pleasure in] the coarsest, commonest pleasures, in the arts of the masses.

. . . the lover of Camp, appreciates vulgarity.

The relation between boredom and Camp taste cannot be overestimated. Camp taste is by nature possible only in affluent societies, in societies or circles capable of experiencing the psychopathology of affluence.

The peculiar relation between Camp taste and homosexuality has to be explained.

[Camp taste is a] gesture of self-legitimation . . . which definitely has something propagandistic about it.

In the modern era, each new style, unless frankly anachronistic, has come on the scene as an anti-style.

In the introduction to her Notes, Sontag calls Camp a sensibility of “artifice and exaggeration . . . a private code, a badge of identity . . . among small urban cliques.”

I think most of these describe DOA Wrestling in 2025. With the exception of the word, “apolitical.”

I’d ask my acquaintance in the “Cat Lovers Against White Supremacy” shirt what he thinks, but that’s probably just his way of dethroning the serious.

Sontag placed the origins of Camp sensibility in the second half of the nineteenth century. Her history extends to the exaggerations of the baroque, but Notes on “Camp” is really a testament to Oscar Wilde, the glorification of the personality as a work of art, in the decadent fin de siècle.

Greenberg, likewise, places the birth of the avant-garde—and its synthetic cousin, kitsch—in the intellectual conscience of the latter 1800s. When, a “superior consciousness of history—more precisely . . . a new kind of criticism of society, an historical criticism,” emerged.

I have to think of this, in the age of Internet personalities, where even podcast intellectuals put their entire personalities on display, on brand. In the new age of our “superior” understanding of history, or more precisely, our criticism of society. Where politics is fashion, and each new style, unless frankly retro, “has come on the scene as an anti-style.” An era when, as Greenberg said of an earlier time, the “elite is rapidly shrinking,” or at least becoming irrelevant, as patrons of culture.

Sontag likewise noted the deterioration of the aristocracy in the late nineteenth century, and the emergence of a new type of dandy as the arbiter of taste—as John Waters said on The Simpsons: “gays.” What Camp was for this contingent—“a private code, a badge of identity . . . among small urban cliques”—kitsch was for the masses. A response to the mass migration of people, especially the proletariat—the new urban worker—from the countryside to the city.

Where Sontag notes the “relation between boredom and Camp,” Greenberg notes that agricultural workers who settled in cities lost their taste for folk culture, and developed “a new capacity for boredom” at the same time.

The new urbanites, with their newfound boredom, created a market for something to replace the folk of the countryside (and here I’m reminded of Greenwich folk singers, pretending to be cowboys and Irish seamen): “ersatz culture, kitsch.” Pop culture. The curation and manipulation of pop culture by “urban cliques” of the “new aristocracy”—sophisticated homosexuals, Sontag would say—was Camp.

Folk culture, much of it oral and musical, was displaced by mass literacy. The proletariat learned to read for the sake of efficiency and survival in a new urban environment, but lacked, for Greenberg, the “leisure and comfort that always goes hand in hand with cultivation of some sort”—the time and disposable income to learn to sculpt, or write like T.S. Eliot, for example.

But mass literacy exposed the majority of people to the memes of the day, in newspapers and ads and popular songs, as digital literacy would expose us to everything-all-at-once. The globalism of its day:

Kitsch has not been confined to the cities in which it was born, but has flowed out over the countryside, wiping out folk culture. Nor has it shown any regard for geographical and national-cultural values. Another mass product of Western industrialism, it has gone on a triumphal tour of the world, crowding out and defacing native cultures in one colonial country after another, so that it is now . . . becoming a universal culture, the first universal culture ever beheld.

We can see the effects of this mechanical revolution, along with the cybernetic one, in today’s so-called Monoculture. And in the ever-evolving “anti-styles” of the so-called Mono-cause, be it #BLM, #LGBT(QIA2S+), #MeToo, #Ukraine, or #Palestine, flowing out over the ethernet. The anti-styles of the #Resistance—political fashions like Cat Lovers Against White Supremacy and Protect Trans Kids—it goes without saying, are complimented by the anti-anti-styles of #MAGA.

If kitsch and camp are products of the city, they have roots, in some sense, in the country—and here, maybe, we approach the paradox of “woke” “rednecks.” I’ll pause here to note that many outsiders migrate to cities like Portland for their image of inclusivity—from red states, yes, but also from rural Washington and Oregon.

The word Camp probably comes from an underground 19th c. slang called Polari, using French or Italian for “to pose in an exaggerated fashion,” se camper or campare. Or it may come from romance terms for the countryside (campo, campagna, etc)—specifically, as novelist Anthony Burgess suggested (using similar slang to great effect in A Clockwork Orange), from military encampments and cruising.

Either way, the function of Polari was code, advertising one’s sensibilities in secret. Polari (Italian parlare, “to talk”) was commonly used, mostly in the U.K., by theater people, circus and carnival performers, criminals, prostitutes, the merchant navy, and… professional wrestlers.

Most of all, it was the lexicon of gay subculture. Lancaster University calls it an “anti-language,” since it was used to subvert anti-homosexuality statutes, and included backslang, or saying a word as if it’s spelled backwards.

Pro wrestling—aka “kayfabe” wrestling, as opposed to athletic grappling—has its roots in folk wrestling. Regional bouts staged at carnivals and fairs, which developed their own sense of theatricality, and slang. “Kayfabe” is carney-speak for the secrets of the business, and may come from Pig Latin for “fake.” It was used among performers to indicate their events were staged, and to “break kayfabe” meant to break character or expose the artifice of the performance. For example, by referring to a wrestler’s birth name, instead of his character’s.

If Polari were spoken in 2025, we might call that a form of “daed gniman.” (Read it backwards).

Anyway, you take my point: there is a long, colorful overlap between wrestling culture and Camp, or queer culture. It’s a wonder that the tropes of professional wrestling weren’t “queered,” to use the language of academic theorists, long ago. That it took as long as it did for the heel Rowdy Roddy to be replaced by the face of Ravenous Randy.

Then again, wrestling has always been a little gay.

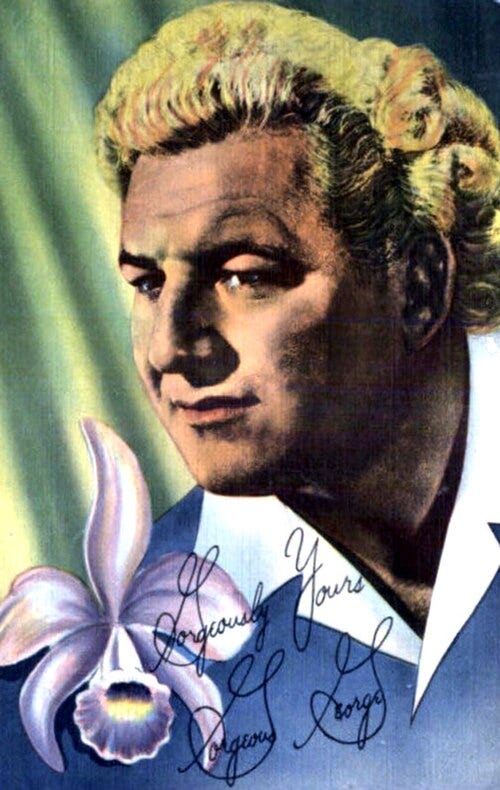

In 1941, George Wagner introduced his new “glamour boy” persona to wrestling fans in Eugene, Oregon. He strode into the ring on a red carpet, accompanied by his valet, “Jeffries,” who carried a silver mirror and spread rose petals at his feet. Jeffries then proceeded to disinfect the mat with Chanel No. 5, for “Gorgeous” George. The difference being that in 1941, Gorgeous George was the bad guy, booed and jeered, and beloved by fans, as their favorite heel.

What’s interesting, and less entertaining, are some of Clement Greenberg’s further remarks about kitsch. Particularly when paired with Susan Sontag’s assertion that Camp is “disengaged, depoliticized — or at least apolitical.”

Greenberg’s words from 1939, that "when enough time has passed the new is looted for new ‘twists,’ which are then watered down and served up as kitsch,” could easily describe the script-flip from Gorgeous George to Ravenous Randy, heel to face. But he continues:

Self-evidently, all kitsch is academic; and conversely, all that’s academic is kitsch. For what is called the academic as such no longer has an independent existence, but has become the stuffed-shirt “front” for kitsch.

Greenberg’s observation, that “Academicism and commercialism are appearing in the strangest places,” might well describe DOA Wrestling in 2025.

To understand what I mean by “academicism,” consider a recent conversation between Mike White, creator of the popular HBO series The White Lotus, and Andrew Sullivan (a podcast intellectual of the sort I alluded to earlier), on Sullivan’s podcast, The Dish.

Incidentally, White and Sullivan are both “cisgender homosexual white men”—though they eschew identifying as such in the jargon of academic theory, unless they’re critiquing it.

Andrew Sullivan introduced the concept of gay marriage legislation in the 1990s, and was roundly criticized for it—by conservatives, of course, but more interestingly, by outspoken members of what Sontag might call the “anti-style” gay left (which might’ve included herself). Gays who derided Sullivan as a conservative for supporting the institution of marriage at all. (At the time; post-2015, most admit he was onto something.)

On Sullivan’s podcast, Mike White discussed his education at Wesleyan, as a double English major, at the university that inspired the 1994 satire film PCU (“Politically Correct University”).

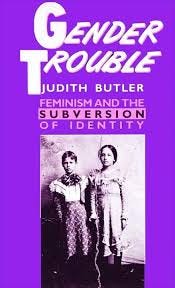

More specifically, the two discussed Michel Foucault and Judith Butler.

Butler’s seminal queer theory tract, Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity, basically laid the groundwork for how the West has been discussing sex and gender since about 2014: Sex is assigned at birth. Gender is a performance. Both are social constructs, not biological. “Men” and “Women” are categories invented by the patriarchy to retain power, and complicated by factors like race, class, and sexuality. The aim of Gender Trouble is to cause gender trouble—to “queer,” or subvert the power structure, especially the language we use to discuss gender and sexuality.

Gender Trouble was published in 1990, a year after Andrew Sullivan published “Here Comes the Groom: A (Conservative) Case for Gay Marriage,” in The New Republic. It took about twenty-five years, but both writers’ ideas have come to fruition. In 1990, Mike White was entering his junior year at “PCU,” or Wesleyan, reading, among other things, books like Gender Trouble.

Judith Butler wouldn’t have a conceptual leg to stand on, if not for Michel Foucault, a French theorist whose seminal “archeologies” of history, Discipline and Punish and The History of Sexuality, were published in 1975-76. Foucault was concerned with the relationship between knowledge and power, and the way discourse—the way we speak about things like sexuality, criminality, insanity—shapes institutions of power. He argued that categories like race and sexuality were social constructs, and that “sites of resistance” could reconfigure power relations. He must’ve been on to something, because the way we conceive of identity and power relations—#MeToo and employer/employee power differentials, #BLM and policing, to pick just two examples—has been shaped by Foucaultian “discourse.”

As a former English major, I assure you the prose of Judith Butler is insufferable. Her style is jargonese, and obfuscates more than it clarifies—though her ideas now seem prophetic. To anyone who’s ever stumbled over a friend’s third pronoun shift, or tongue-twisted their way through the American Medical Association’s new four-word euphemism for “woman,” they have Judith Butler to thank.

Foucault’s writing is a bit more compelling. His theories are based on fascinating histories, of insane asylums, penitentiaries, or the church. They don’t as a rule defy intelligibility—when he argues that sexuality is a construct, he points to the Victorian era, and shows how the trial of Oscar Wilde inspired a new psychological classification, “the homosexual,” for individuals who were previously diagnosed and criminalized not by immutable identity categories but as practitioners of sodomy. And yet, the ultimate result of the penetration of Foucault’s ideas, and Judith Butler’s, into popular discourse is the reduction of all relationships to identity, language, and power. #SitesofResistance.

Mike White explained how intoxicating it was to be exposed to these theories in 1989-92, when they were taking root in academia. But ultimately, how unfulfilling it was, as a double English major, reading not works of literature but books of theories about works of literature, without reading what post-structuralists—this branch of theory—were “deconstructing,” or trying to tear down: the art itself.

In this sense, deconstructionism is, to borrow Clement Greenberg’s words: “Kitsch, using for raw material the debased and academicized simulacra of genuine culture.” Something that “welcomes and cultivates this insensibility.”

So when Greenberg says, “Academicism and commercialism are appearing in the strangest places,” I look around the wrestling arena, away from the symbolic power struggle between gender-fluid men and Hells Belles, or Mexicans and whites, or the cisgender gay man and menstruating woman, and notice mass-produced Cat Lovers Against White Supremacy t-shirts, and Protect Trans Kids with the dagger and rose. I see “the stuffed-shirt ‘front’ for kitsch,” the academic.

Art, is more than advertising or propaganda. As White told the Wesleyan Argus in 2021:

“I feel like the purpose of art is not necessarily moral pedagogy . . . It’s more like hanging out with a person who has a hodgepodge of thoughts . . . People can extrapolate different things, and it can be a Rorschach test of how people see . . . I get a lot of criticism, especially when people look at [The White Lotus] through the prism of activism and say that the purpose of art is to have a message and not to muddle the message. That’s just the opposite of how I approach things.”

It gets even less entertaining, I’m afraid, viewing wrestling through the eyes of Clement Greenberg.

I want to preface this with an acknowledgment that, when read in excerpt, in 2025, Greenberg sometimes has the ring of an elitist snob. The New Yorker, the symbol of elitism itself, he called “fundamentally high-class kitsch for the luxury trade,” that “converts and waters down a great deal of avant-garde material for its [readers].” But, considering some of what I’ve said about academicism, and some of what I’ve read in The New Yorker lately, he’s not entirely wrong.

In the following passage, he talks about class and refers to the “common man” as “plebeian”—but remember that this is 1939, Greenberg was going through a Trotsky phase, and that’s what Marxism, like Foucaultianism or Butlerism, does: reduces everything to a power struggle, in this case, class. Also, he’s criticizing elitism historically, patrons of art like the church or nobility, and how that’s changing on the eve of WWII. His words are chilling.

It is a platitude that art becomes caviar to the general [public] when the reality it imitates no longer corresponds even roughly to the reality recognized by the general.

Even then, however, the resentment the common man may feel is silenced by the awe in which he stands of the patrons of this art.

Only when he becomes dissatisfied with the social order they administer does he begin to criticize their culture. Then the plebeian finds courage for the first time to voice his opinions openly . . .

Most often this resentment toward culture is to be found where the dissatisfaction with society is a reactionary dissatisfaction which expresses itself in revivalism and puritanism, and latest of all, in fascism.

Here revolvers and torches begin to be mentioned in the same breath as culture. In the name of godliness or the blood’s health, in the name of simple ways and solid virtues, the statue-smashing commences.

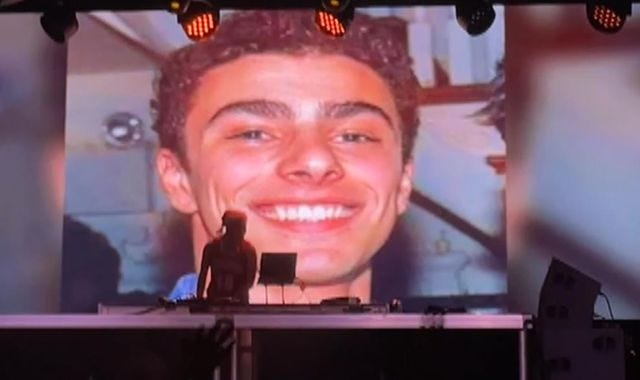

Well, I certainly remember statue-smashing, and puritanism. I wrote about it, here. I remember tiki torches, and Molotov cocktails. And it’s hard to forget Bop to the Top, the Disney-themed dance party where a DJ played Hannah Montana’s “He Could Be the One” in front of an enormous projection of Luigi Mangione, the suspect who murdered UnitedHealthcare CEO Brian Thompson with a 3D-printed Glock. “You gotta give the people what they want,” the DJ told the crowd.

This no longer corresponds even roughly to the reality I recognize.

Researching all this, I turned to my Bible of American culture, A New Literary History of America, looking for entries on Sontag and Greenberg. What I found instead was an essay by Carlo Rotella, “The End of American Sporting Life”—September 21, 1955: Rocky Marciano knocks out Archie Moore at Yankee Stadium.

The way Rotella describes boxing between the Victorian era and the 1960s recalls the collapse of high and lowbrow culture during the same period that concerned Sontag and Greenberg.

Here boxing sounds like an art, and knowing something about boxing was connoisseurship: a “common piece of equipment in the toolbox of American cultural competence,” for all classes—“especially the section of it devoted to masculinity.” On the upper end, you had A.J. Lieberman, publishing his fight pieces in that “high-class kitsch for the luxury trade,” The New Yorker. These were collectively published in 1956, as The Sweet Science.

In them, Liebling elegizes the golden age of boxing, felled by some of the same forces that produced kitsch: mass literacy, full employment, late school-leaving age, and above all, television. In The Sweet Science, Rotella explains, “Rocky Marciano, a TV star, ushers in the new order” by beating Archie Moore.

The culminating essay about this fight, “Ahab and Nemesis,” in Rotella’s opinion, is not only one of the great essays on boxing but one of the great essays of all time. Extracting “nuggets of meaning from a fight is Liebling’s great subject,” and to do so, he “mixes registers and allusive gestures up and down the highbrow-lowbrow spectrum.”

To follow Liebling’s account of the second round, for example, “the reader needs to know something about opera, Melville, Euclid, and Aristotle’s Poetics. At other points Liebling compares Archie Moore not only to Faust and Ahab but to the ballerina Margot Fonteyn, the pianist Arthur Rubenstein, the statesman Winston Churchill, the director Orson Welles, Camus’s Sisyphus, and a Japanese print entitled ‘Shogun Engaged in Strategic Contemplation in the Midst of War.’”

For Liebling, Archie Moore represented poetry in motion, and his defeat at the hands of brute-force Rocky Marciano, whose fans he called “basically anti-intellectual,” was “a crushing defeat for the higher faculties and a lesson in intellectual humility.”

For Rotella, The Sweet Science clearly represents a kitschy collapse of high and lowbrow. It’s Liebling’s “self-portrait as a typical urban intellectual, a child of the middle class drawn to both the library and the street.” Liebling’s style influenced New Journalism, which would further combine intellectual writing with slick magazines like Playboy and Rolling Stone.

Rocky Marciano, you might say, represented the triumph of the popular over the poetic in pugilist sport—or at least the collapse of one into the other. There is certainly poetry in the silver age of boxing, in Muhammad Ali’s “float like a butterfly, sting like a bee.”

Rocky Marciano, as you might suspect, was one of the key inspirations for Rocky Balboa, played by Silvester Stallone.

If the triumph of Rocky Marciano over Archie Moore represented a crushing defeat for the higher faculties, where does the crushing defeat of Rocky Balboa at the hands of Hulk Hogan leave us, in round two of Rocky III?

I don’t care to know. But I’ll hazard a guess.

Wrestling is the ultimate simulacra of politics. It’s not Susan Sontag’s cup of Camp, but it is kitschy, and there is definitely something propagandistic about it.

Terry Bollea, as “Hulk Hogan,” warmed up the crowd for Donald Trump at the 2024 Republican Convention. Bollea was undecided, he told Fox News before the convention, until the first assassination attempt—“When I saw him stand up with that fist in the air and the blood on his face — as a warrior.” “You never know,” Bollea said in a previous interview, still debating which political party to support. “Right now, I’d make a great vice president, brother, because I do have common sense. I do know right from wrong.” Onstage at the 2024 convention, he pointed to Trump and J.D. Vance, and called them “the greatest tag team of my life.”

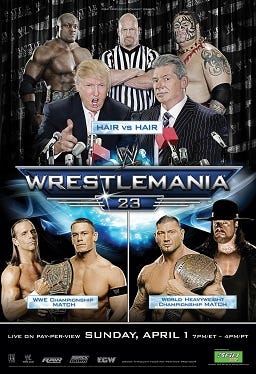

In 2016, writers like Matt Taibbi opined that the best way to understand Donald Trump—who is friends with Vince McMahon; and competed against the wrestling magnate in a 2007 WWE “Battle of the Billionaires: Hair vs Hair,” which resulted in the shaving of McMahon’s head; and was himself inducted into the WWE Hall of Fame in 2013—is to understand him as the consummate political heel.

And of course there’s the hair and makeup, and the drag queen jokes. And the logo of CNN superimposed over Vince McMahon’s face, as Trump pummeled his fellow billionaire in a doctored video from “Hair vs Hair.”

In response to this you have the anti-style, DOA Wrestling. Torches and revolvers, and stenciled images of daggers and rose. The C.L.A.W.S. are out—Cat Lovers Against White Supremacy.

People love a clear-cut bout between good and evil, or at least a clear understanding of which side to take. The only DOA bout where the demarcation between “heel” and “face” was murky—call it Wayne’s World vs Bare Naked Ladies—was between a longhaired guy in black skinny jeans and trucker hat, and a stocky rocker with frosted tips, whom Wayne’s World called a poser. I got more confused looks when I made the mistake of noticing, “You’re both posers!” than the dude in the neck beard who screamed at Cole Rivera, “You suck dick!”

Tragically ludicrous, yes.

He knew who the heel was.